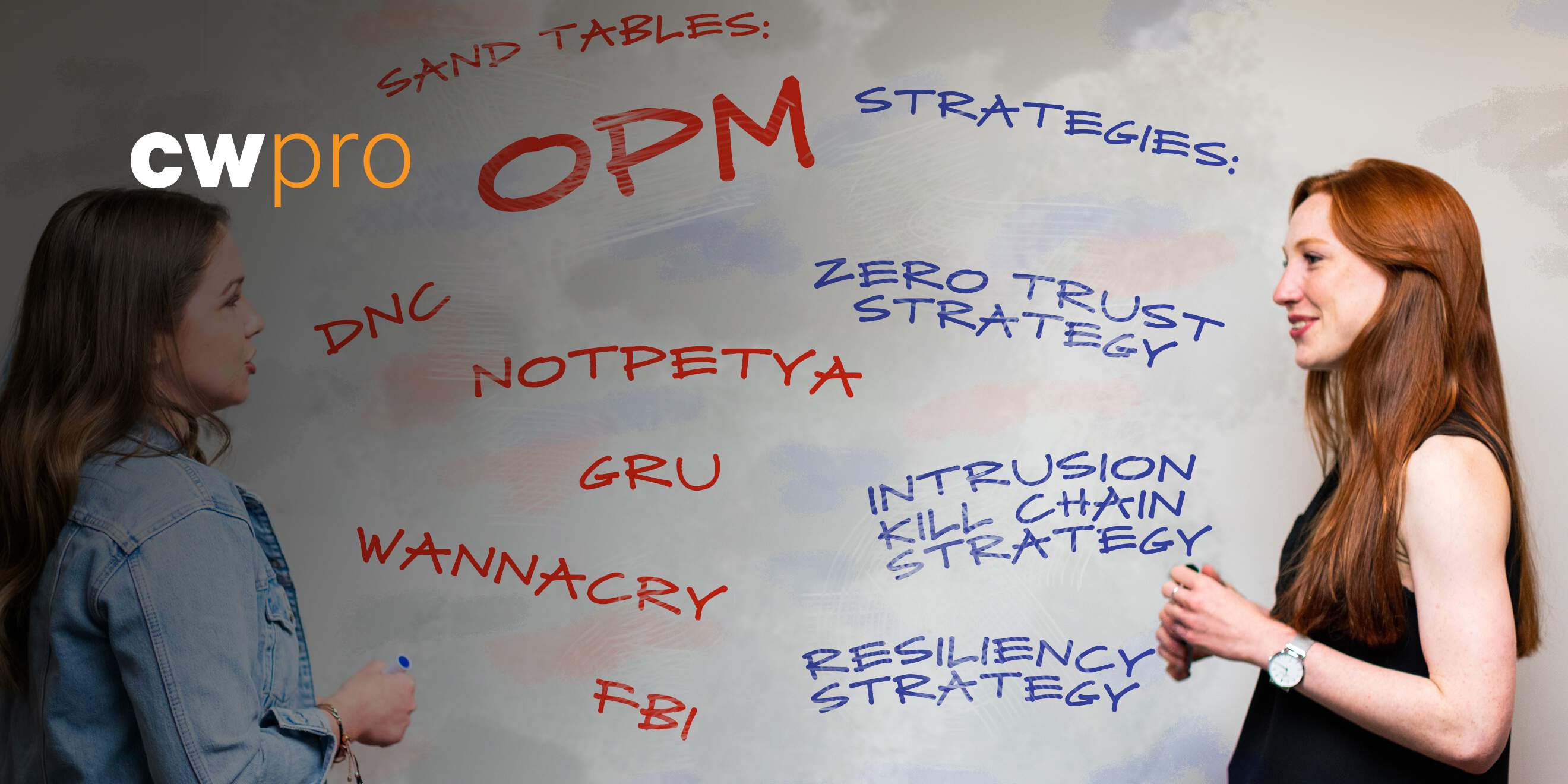

Cyber sand table series: 2014 OPM hack.

Rick Howard: Last year, I did an episode called "Introducing the cyberspace sand table series: The DNC compromise." I got the idea from my old military days when, after my unit completed an on-the-ground field exercise, the leaders would all gather around the map board for a hot wash and replay the exercise to see what we could learn. For future exercises and, more importantly, future battles, we would want to repeat all the good things we did and forget all the things that didn't work. If we were really fancy, we would use an honest-to-goodness physical contour map, complete with sand to represent the terrain - thus the phrase sand table - and plastic army soldiers to represent the units on the ground - or, you know, rocks and twigs, whatever we had handy.

Rick Howard: Now, since some network defenders don't like using the military metaphor in conjunction with infosec, I made the point that hot washes were no different from when Tom Brady, the recently retired and perhaps most successful NFL quarterback of all time, studied hours of game film each week to prepare for his next contest. I made the case that we, as network defenders, might learn a lot by adopting some version of these sand table exercises or, if you will, game film reviews to learn how to improve our own digital defenses.

Rick Howard: I started by walking us through the infamous Russian compromise of the Democratic National Committee in 2016. In this show, I'm going to dust off the sand table and reset it for 2013, the Chinese compromise of the U.S. government's Office of Personnel Management, or OPM. This is going to be fun.

(SOUNDBITE OF FILM, "JURASSIC PARK")

Samuel L. Jackson: (As Ray Arnold) Hold on to your butts.

Rick Howard: My name is Rick Howard, broadcasting from the CyberWire's secret sanctum sanctorum studios, located underwater somewhere along the Patapsco River near Baltimore Harbor. And you're listening to "CSO Perspectives," my podcast about the ideas, strategies and technologies that senior security executives wrestle with on a daily basis.

Rick Howard: Let's start setting up the sand table with the blue team pieces - the Office of Personnel Management, or OPM. According to the U.S. Congressional Research Service, Congress established the federal civilian workforce when it passed the Pendleton Act in 1883. Nothing significantly changed until President Jimmy Carter signed the 1978 Civil Service Reform Act, which, among other things, created OPM and gave the new organization responsibility for human capital management, benefits and vetting. Essentially, OPM became the HR department for federal civilian employees.

Rick Howard: In 1996, almost 20 years later, OPM contracted the vetting piece of their mission to a commercial company, the U.S. Investigation Services, or USIS, in an effort to save costs. In 2009, almost 10 years later, they added two more contractors, KeyPoint and Khaki. This is important because the Chinese hackers, most likely the adversary group called Deep Panda, used USIS and KeyPoint as a third-party digital supply chain attack vector. In other words, Deep Panda compromised the USIS and KeyPoint networks first and then used the credentials they stole there to legitimately log in to the OPM network. More on that in a bit.

Rick Howard: But in 2005, OPM took on the additional vetting mission for the U.S. military, which made it responsible for over 90% of all background investigations for the federal government. Let's be clear here, though, the difference between typical stored commercial HR data compared to what OPM stores is massively in-depth history.

Rick Howard: A commercial HR department might store your name, address, education and past four or five jobs. OPM stores all of that plus every place you've lived and all of your friends and acquaintance names and contact info for the past 10 years. They also keep track of all of your family members. Compound that information with any legal trouble you might have had or any subversive or illegal habits like drug and alcohol use, DWIs, adultery, et cetera, plus organizational affiliations you had during that time, ranging anywhere from your daughter's travel soccer team to that one time when you were in college and donated money to the Communist Party as a joke, allegedly. That's a lot of information.

Rick Howard: In 2007, an investment firm called Providence Equity Partners bought USIS and implemented extreme cost-cutting measures to increase profits. USIS investigators began approving clearances without actually doing the required investigations for a large number of cases. At the end of every month, they would flush unfinished investigations to meet their profit quota. In other words, they approved candidates without doing the investigation and got paid for each. Unfortunately, OPM didn't discover the fraud for another five years.

Rick Howard: In 2011, USIS became the subject of a whistleblower lawsuit where an insider claimed that USIS used a proprietary computer software program to automatically release OPM background investigations that had not gone through the full review process and thus were not complete - unbelievable. In terms of workforce size, OPM estimates a total federal workforce of 2.1 million civilian workers. The Department of Veterans Affairs estimates about 19 million U.S. veterans, and the Council of Foreign Relations estimates about 1.3 million active-duty personnel.

Rick Howard: OPM stores vetting material for all of these groups. And that's a lot of people. In terms of espionage and counter-espionage operations, any foreign entity that could get their hands on that data would have a gold mine. They could use it to blackmail federal workers and military personnel to reveal secrets or disrupt important projects or operations. Since the data collected lists all foreign context for the past decade, they would have a rich source of potential double agents to track down and neutralize, setting back intelligence collection for years. Not to put too fine a point on it, but the dataset will be useful for the next 50 years, since it will take that long for the current set of employees and military to age out of the system.

Rick Howard: In the 2016 report on the OPM breach published by Congress, the title of the report sums up the impact - quote, "The OPM Data Breach: How the Government Jeopardized Our National Security for More Than a Generation," end quote.

Rick Howard: Now, regular listeners to this podcast know that I'm a big believer in first-principle thinking. As security professionals, our first-principal task is to reduce the probability of material impact due to a cyber event. OPM is a giant bureaucratic U.S. federal government organization. Leaders of that institution have many things on their plate, but OPM leadership had known for years that their internal security posture was garbage.

Rick Howard: Between 2005 and 2014, OPM had four directors. Their own internal inspector general told them all, year after year, that the data they hosted was extremely sensitive and valuable and that security measures they had in place had material weakness, significant deficiencies and concerns and was getting worse. None of the four directors thought that the data they stored was material enough to their organization and, indeed, to the entire U.S. government to actually spend resources to improve the situation. Before the breach, OPM didn't know where the copies of all the data were located, and they didn't even have a security team.

Rick Howard: Let's turn our attention to the Deep Panda side of the sand table. The origins of the Chinese cyberattack capability can be traced to a white paper later turned into a book published by two People's Liberation Army colonels, Qiao Liang and Wang Xiangsui, in 1999. They developed their thesis after watching the U.S. military's utter dominance of the Iraqi army in the 1991 Persian Gulf War. They concluded that any nation - but especially China - going toe to toe with the U.S. in a conventional military fight could only result in, at best, a standoff with massive damage on both sides and, at worst, utter destruction to the American opponent. They proposed instead something called unrestricted warfare.

Rick Howard: In an interview about the book, Colonel Qiao said, quote, "the first rule of unrestricted warfare is that there are no rules, with nothing forbidden," end quote. And if that sounds eerily similar to the line from the famous movie "Fight Club" released around the same time of the book, 1999, it's not. I thought so, too, but I checked. The line from the movie is...

(SOUNDBITE OF FILM, "FIGHT CLUB")

Brad Pitt: (As Tyler Durden) The first rule of Fight Club is you do not talk about Fight Club. The second rule of Fight Club is you do not talk about Fight Club.

Rick Howard: Qiao and Wang had a different view altogether. Unrestricted warfare means that you don't fight based on the rules set by the superior opponent. Tyler Tidwell, in reviewing the book, says that the two authors proposed to radically expand the conventional military battle space into financial markets, television, cyberspace and outer space. In fact, he says that physical tank-on-tank violence is the last refuge; you never want to get there.

Rick Howard: Interestingly, the Chinese Unrestricted Warfare Doctrine is pretty close to the Russian Gerasimov doctrine, established in 2014, some 16 years later. Now, policy wonks will argue with me on whether these ideas constitute an actual national doctrine, and I'm confident I would lose those debates. But the one thing I'm sure of is that the big five cyber nations - China, Russia, North Korea, Iran and the U.S. - and lots of other nations who are dabbing their feet in the cyber pool - India, Pakistan, Palestine, Israel and Vietnam - have determined in the last two decades that they can get a whole lot more done in terms of national objectives by pursuing, as David Sanger says in his book, "The Perfect Weapon," a continuous, low-level cyber conflict. It's low level because it rarely crosses a line that might start an actual tank-on-tank battle, but the effects can be devastating. And China was one of the first nations to jump into the cyber pool and have a major impact.

Rick Howard: My editor, John Petrik, points out that unrestricted warfare is really an extension of asymmetric warfare, and he would be right. According to John, the granddaddy of asymmetric warfare was the French naval theory from Jeune Ecole - again, my French is awful - who thought the inexpensive torpedo boat rendered the battleship obsolete. Britannica Online defines asymmetric warfare as, quote, "unconventional strategies and tactics adopted by a force when the military capabilities of belligerent powers are not simply unequal but are so significantly different that they cannot make the same sorts of attacks on each other," end quote. This is guerrilla warfare, and weaker forces have used the strategy against stronger forces since the 6th century. In more modern times, guerrilla warfare defeated the U.S. in Vietnam and in Afghanistan.

Rick Howard: The genius of Qiao and Wang, though, is extending the idea to cyberspace. In 2003, U.S. military network defenders discovered that Chinese cyber operators had inserted themselves into large swatches of military networks around the world. I was the commander of the U.S. Army Computer Emergency Response Team, the ACERT, back then. And military leadership classified that activity with a really cool code name called Titan Rain.

Rick Howard: Before Titan Rain, the most serious hacker I tracked at the ACERT was a British citizen, Gary McKinnon, who was confident that if he poked around enough military networks, he was sure to find the evidence that aliens existed. We were all kind of secretly hoping that he'd be successful.

Rick Howard: After Titan Rain, all the military cyber defenders started operating at a different level. Instead of defeating the low-level cybercriminals, we were now laser-focused on nation-state cyber-espionage activity. By 2006, the general public started to learn that the U.S. wasn't the only Chinese target. Chinese cyber operators compromised Taiwan's Ministry of National Defense and the American Institute in Taiwan. In 2007, the Chinese found their way into the U.S. Office of the Secretary of Defense and German government entities that included the Federal Chancellery, the Ministry of Economics and Technology and the Federal Ministry for Education and Research.

Rick Howard: At the same time, the public started to learn that the Chinese weren't just interested in government secrets. They were after business intelligence, too. That same year, 2007, the British domestic intelligence service, MI5, alerted 300 business leaders, warning that the People's Liberation Army, or PLA, targets confidential business information. Five years later, in 2012, Keith Alexander, when he was the National Security Agency director and commander of the U.S. Cyber Command - and by the way, he was my senior raider when I was at the ACERT - said...

(SOUNDBITE OF ARCHIVED RECORDING)

Keith Alexander: In fact, in my opinion, it's the greatest transfer of wealth in history.

Rick Howard: Around 2008 and probably as early as 2006, the Chinese penetrated the Lockheed Martin classified network and stole the plans related to the American F-35 fighter jet. That same year, they compromised the election campaigns of both Senator Obama and Senator McCain, as well as the White House information system and NASA's Kennedy Space Center and Goddard Space Flight Center.

Rick Howard: A Canadian research team in 2009 published intelligence on the GhostNet cyber-espionage campaign that targeted government embassies from Germany, the Philippines, India, Pakistan, Portugal and the Tibetan government in exile. And then, in early 2010, Google sent out shock waves when it announced that it had been hacked by the Chinese government. When all was said and done, two different Chinese government entities in separate and uncoordinated missions had established a persistent presence within the Google networks - the PLA, who stole intellectual property - specifically, they went after the source code from tech companies - and the Ministry of State Security, or MSS, who targeted political dissidents like the Dalai Lama, the Uyghurs and the Tibetan ethnic minorities.

Rick Howard: The announcement was a shock wave because before, no commercial company would ever admit in public that it had been compromised by some cyber adversary for fear of risking its reputation on the stock market. Google opened the door for everybody. Today, nobody even blinks twice when we hear about another breach.

Rick Howard: Just as an aside, the Cybersecurity Canon Hall of Fame candidate book "This is How They Tell Me the World Ends" by Nicole Perlroth has the most complete account of the Google compromise that I have ever encountered. For that alone, the book is probably worth reading.

Rick Howard: In 2011, the Chinese government stole the key material that was the essential secret sauce used in the RSA secure token two-factor authentication product and later used that intelligence to compromise Lockheed Martin. And the irony isn't lost on me that the famous Beltway bandit U.S. contracting company Lockheed Martin, the company responsible for arguably the greatest innovation in cybersecurity strategy - inventing the intrusion kill chain prevention model in 2010 - was the victim of not one but two major Chinese cyber-espionage campaigns around the same time - the F-35 fighter jet espionage operation and the compromise of the RSA secure token two-factor authentication product.

Rick Howard: All of this activity, from about 2003 to 2012, sets the stage for what can arguably be classified as the most impactful cyber-espionage campaign that is known to the public - the OPM breach of 2013.

Rick Howard: Turn one - Deep Panda, the red team, from July 2012 to March 2014. Using the Lockheed Martin intrusion kill chain model as a guide, it's unclear how Deep Panda gained initial access to the OPM uses and key point networks. With all the analysis after the fact from OPM's IT team, two security vendors, Cylance and CyTech, and a congressional committee, how Deep Panda conducted early recon missions and exploited the first victim machines is unknown. This is mostly because OPM wasn't logging anything useful in terms of threat intelligence.

Rick Howard: What is known is that another Chinese adversary group, commonly referred to as Axiom but also attributed to China's second bureau of the People's Liberation Army, Unit 61398, managed to sneak a piece of malware, Hikit, onto the OPM network as early as July 2012 but probably much sooner. The US-CERT notified OPM that something was beaconing out to a Chinese-owned command and control server. Axiom and Deep Panda are not the same adversary group if you compare the steps each takes across the intrusion kill chain. But it's not a big stretch of the imagination to speculate that the Chinese government would use one group to establish initial access and another group to perform lateral movement and exfiltration operations. Today's cybercriminals do it all the time. Probably sometime in 2013, Deep Panda established a command-and-control server called opmsecurity.org.

Rick Howard: The owner of the domain was listed as Steve Rogers. Marvel Cinematic Universe fans will recognize the name as the alter ego to Captain America, thus proving again that hackers are science fiction and fantasy fans, too.

Rick Howard: Recall that the code developed by the Russians in the NotPetya attacks against Ukraine was riddled with references from a famous and beloved science fiction book entitled "Dune," written by Frank Herbert back in 1965 long before the "Dune" movie came out last year. Andy Greenberg's Cybersecurity Canon Hall of Fame book on NotPetya is even called "Sandworm," a reference to the mythical beast that inhabits the planet Arrakis and the source of all the drama in the first book.

Rick Howard: By April 2013, Deep Panda had established a beachhead on the USIS network. They stole legitimate credentials from USIS employees and used them to log on to the OPM network. Once there, they began reconning for useful information. By November, they had exfiltrated manuals of IT system architecture, giving them the blueprints of how to navigate the OPM networks. And by December, Deep Panda had exploited the first victim machine on the KeyPoint network.

Rick Howard: Turn one, OPM, the blue team this time, from January 2014 to April 2014. In January of 2014, on the back end of the 2011 whistleblower complaint, the U.S. Justice Department sued USIS in a 25-page complaint filed in the U.S. District Court in Montgomery, Ala., claiming from 2008 to 2012, about 40% of the company's investigations were fraudulently submitted. Newspaper headlines highlighted the many incomplete cases, but two were particularly memorable. USIS approved the background checks for the government insider Edward Snowden, who leaked classified documents to the public in June 2013, and for the mentally unstable Navy Yard shooter who killed 12 people in Washington, D.C., in September 2013.

Rick Howard: In the meantime, through no fault of their own, the OPM IT team had not a single security prevention tool deployed on their networks. They tried to convince their leadership to do something over the years, but OPM directors rejected all requests. Instead, leadership relied on outside entities to monitor their networks for them, like the US-CERT and the U.S.-government-developed EINSTEIN intrusion detection system that was positioned outside of the OPM networks proper. Throughout the entire attack, the EINSTEIN system didn't detect any Deep Panda activity at all. Three months later, on 20 March, the US-CERT notified OPM again of more data exfiltration. The last time was July 2012.

Rick Howard: OPM investigators determined that since the stolen data didn't contain PII - or personal identifiable information - and that the hacker was confined to a certain part of the network, OPM leadership didn't have to go public with the incident. Note - why the OPM IT team thought that Deep Panda was confined to a certain part of the network when they had no way to confine them deployed is a mystery - end note.

Rick Howard: They decided that the best course of action was to monitor the threat in order to gain counterintelligence and to start planning what they called the big bang - a system reset that would purge the attackers from the system. The OPM CIO, Donna Seymour, approved the plan five days later. Note - let me just point out here that an IT team with no security experience, no security tools deployed and no logging telemetry to speak of decided to monitor the hacker to gain intelligence. Incredible - end note. On 21 April, an OPM contractor from SRI found another piece of malware that communicated with the command-and-control server, opmsecurity.org, that Deep Panda had established in 2013.

Rick Howard: One last thing for this round. On 21 April, which happens to be my birthday, by the way, an OPM contractor from SRA found another piece of malware that communicated with the command-and-control server, opmsecurity.org, that Deep Panda had established in 2013.

Rick Howard: Turn two, Deep Panda, the red team, from May 2014 to March 2015. On 7 May, using credentials stolen from the KeyPoint network, Deep Panda legitimately logged into the OPM network and installed a remote access trojan, or RAT, called PlugX on roughly 10 machines for command-and-control purposes. PlugX had been around as far back as 2008 and had been used by several Chinese adversary groups in the past. APT1, 3, 27, 41, DragonOK, GALLIUM, Mustang Panda and TA459. By 27 May, 20 days later, Deep Panda began installing key logger software on database administrators' workstations. And on 5 June, they installed malware on a KeyPoint web server. Fifteen days later, 20 June, they began extended remote sessions with OPM servers containing sensitive data, and they probably gained access to the OPM mainframe on 23 June.

Rick Howard: By July, Deep Panda had discovered the OPM jump server, a kind of toll booth that stands between the day-to-day networking resources and sensitive data resources - in this case, the OPM background check data on all federal employees and military personnel. If you want to access the crown jewels, you have to go through the jump server. Deep Panda installed a PlugX variant on the jump server and, according to the congressional report, quote, "during the long Fourth of July weekend, when staffing was sure to be light, the hackers began to run a series of commands meant to prepare data for exfiltration," end quote. Deep Panda collected batches of personal information wrapped in .zip or .rar files and stored them on hard drives for later exfiltration. Those file types are archive file formats that support data compression.

Rick Howard: On 21 July, OPM director Katherine Archuleta downplayed the 20 March breach in an ABC interview. Quote, "we did not have a breach in security. There was no information that was lost. We were confident as we worked through this that we would be able to protect the data," end quote.

Rick Howard: Here's Congressman Jason Chaffetz, a Democrat from Utah, grilling Director Archuleta on that statement in the congressional hearings in 2016, two years later.

(SOUNDBITE OF CONGRESSIONAL HEARING)

Jason Chaffetz: So, Ms. Archuleta, when we rewind the tape and look at the WJLA TV interview that you did on July 21, you said, again, we did not have a breach in security; there was no information that was lost. That was false, wasn't it?

Katherine Archuleta: I was referring to PII.

Jason Chaffetz: No, you weren't. That wasn't the question. That was not the question. You said - and I quote - "there was no information that was lost." Is that accurate or inaccurate?

Katherine Archuleta: The understanding that I had of that question at that time referred to PII.

Jason Chaffetz: It was misleading, it was a lie, and it wasn't true.

Rick Howard: At the end of July 2014, Deep Panda established another command-and-control server - opmlearning.org, this time registered to Tony Stark, the alter ego of Iron Man in the Marvel Cinematic Universe.

(SOUNDBITE OF MUSIC)

Unidentified Singer: (Singing) Tony Stark makes you feel. He's a cool exec with a heart of steel.

Unidentified Chorus: (Singing) And Iron Man...

Rick Howard: Fifteen days later, on 16 August, the malware installed by Deep Panda on the KeyPoint web server back on 5 June, 2014, stopped functioning. But by the end of August, Deep Panda had exfiltrated all the data they had collected in .zip and .rar formats, and this is all the detailed information for some 20 million federal civilian employees and military personnel. By 20 October, 45 days later, Deep Panda used OPM credentials to bridge over to the U.S. Department of the Interior, which held another 4.2 million personnel records.

Rick Howard: And at this point, Deep Panda's mission is almost complete at OPM, so they turn their attention to Anthem, a U.S.-based insurance company. They already gained access to the Anthem network sometime in April 2014. In December, the group exfiltrated some 80 million customer records. In February 2015, a commercial intelligence firm, Threat Connect, discovered that the Anthem attackers used the same Tony Stark-registered command-and-control server that OPM hackers used - in other words, Deep Panda. And the last nail in the coffin, on 26 March, 2015, Deep Panda exfiltrated just over 5.5 million fingerprint records of federal employees.

(SOUNDBITE OF BRUCE SPRINGSTEEN SONG, "BORN IN THE U.S.A.")

Rick Howard: Turn two, OPM, the blue team, from May 2014 to December 2014. On 27 May, 2014, OPM executed its big bang strategy and thought they were successful. Unfortunately, they didn't know about the Deep Panda's compromise of KeyPoint and how Deep Panda stole legitimate OPM credentials. OPM technicians had no visibility of Deep Panda's key logger installs onto the OPM systems, remote sessions with OPM sensitive servers, access to the OPM mainframe and the collection and storage of background investigation data.

Rick Howard: On 10 June, just over 10 days later, OPM CIO Donna Seymour testified before the Senate Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs Subcommittee on her strategic information technology plan. She didn't mention any of this because she didn't know about it, but she also didn't mention Deep Panda's activity from March through May, which she did know about because she approved the big bang plan.

Rick Howard: Two days later, on 12 June, the OPM tech team deployed an evaluation copy of one of Cylance's security products. This is the first OPM security detection tool ever deployed. They hadn't purchased it yet; the product was just a feature-reduced demo. Ten days later, on 22 June, the Department of Homeland Security released an incident report for OPM's first breach discovered back on 20 March.

Rick Howard: In an interview with The New York Times a month later, on July 9, an OPM spokesperson acknowledged the March 2014 breach but emphasized that they lost no PII, just manuals and technical documents. This is absolutely true because, as I said, they didn't know about the KeyPoint compromise yet. They did neglect to say that some of the technical documents were blueprints of the OPM networking architecture.

Rick Howard: A month later, in August, USIS notified OPM regarding their breach back in 2013, over a year after the fact. USIS leadership acknowledged the loss of some 25,000 government employee records. OPM responded by issuing a stop-work order on 6 August until everything could be sorted out.

Rick Howard: The USIS delay in notifying OPM about their breach, coupled with the Justice Department's whistleblower lawsuit on fraudulent work practice, convinced OPM to decline to renew the USIS contract in September, but the damage had been done in two parts - massive fraud in not conducting background checks for years and a digital supply chain entry point for Deep Panda. That left Khaki and KeyPoint as the remaining contractors conducting background investigations. Later that year in December, KeyPoint announced that it had been breached to the tune of 4.2 million records exfiltrated.

(SOUNDBITE OF SONG, "BORN IN THE U.S.A.")

Bruce Springsteen: (Singing) Born in the USA. Got in a little...

Rick Howard: Turn three, OPM, the blue team, from April 2015 to June 2015. Sometime in the spring of 2015, OPM discovered evidence of the remote sessions between Deep Panda and OPM's sensitive servers over a year after the sessions happened. On 9 March, they thought they'd shut down the communication between the OPM networks and the Deep Panda command and control server, opmsecurity.org registered to Steve Rogers. But a month later, on 15 April, OPM's investigators discovered more Deep Panda command and control beaconing to opmsecurity.org with the Cylance evaluation product.

Rick Howard: As they notified the US-CERT about the traffic, they realized that Deep Panda still had a foothold in their system. The next day, 16 April, almost a year to the day since Deep Panda's first initial access, OPM leadership finally assigned a person, Curtis Mejeur, to eradicate the advisory group from the OPM network. His first move was to ask for Cylance's help using the demo product to diagnose forensic images of OPM servers. The demo product wasn't built for that. OPM needed a tool with more capabilities. Cylance agreed to let OPM use their upgraded product Cylance Protect in a free trial mode on 2,000 devices. And according to the congressional report, the product lit up like a Christmas tree with widespread infections.

Rick Howard: Three days later, on 19 April, a Cylance technician discovered a rare Deep Panda mistake. When Deep Panda finished the exfiltration of all the data back in December, they forgot to delete at least dot-RAR file. That gave the Cylance technician the lead to discover the massive data exfiltration. In an email to a CEO, Stuart McClure, explaining the discovery, he said, quote, "they are (unintelligible), by the way," end quote.

Rick Howard: According to the congressional report by 21 April three days later, besides all the Deep Panda evidence discovered by the Cylance Protect product, it also detected some, quote, "2,000 individual pieces of malware that were unrelated to the attack in question, everything from routine adware to dormant viruses," end quote. More importantly, the product also discovered the Plug X variant. It was only present on about 10 OPM machines, but they were key machines, including the jump server.

Rick Howard: On the same day, 21 April, another commercial vendor, CyTech, arrived at OPM for a long scheduled appointment to demonstrate their cipher product. According to the congressional report, quote, "the breach was not public knowledge at this point, and OPM staff did not share any information about it with company founder Ben Cotton, who was there to lead the demo. Cipher also detected the malware, and Cotton immediately agreed to help with the response," end quote. According to CyTech, at the end of the entire incident, OPM owed them over $800,000. But because no contract was put in place, CyTech was never paid.

Rick Howard: Two days later, on 23 April, OPM finally decided that it had a major breach on its hands involving the loss of PII. That triggered a requirement to notify Congress. The next day, 24 April, in conjunction with a scheduled power outage as part of a Washington, D.C., power grid modernization program, OPM eradicated all the malware that had been previously discovered. Back then, two days later, 26 April, Cylance engineers discovered evidence of the command and control sessions from important and sensitive servers back in June 2014, which triggered another notification to Congress. In May, they discovered yet another large-scale exfiltration and that triggered a third requirement to notify Congress. Finally, on 4 June, OPM briefed the media about the breach.

Rick Howard: The Committee on Oversight and Government Reform in the U.S. House of Representatives held the first of two hearings on 16 June. Three days later, 19 June, the commercial security vendor FireEye attributed Deep Panda first discovered in the wild by another security vendor, CrowdStrike, as the adversary group that conducted attacks against OPM. At least they used some of the same tactics. But Director Archuleta repeatedly told the House Oversight and Government Reform Committee that she couldn't say if any PII was lost in the 2014 hack but didn't mention any of the most recent developments. According to the National Review, quote, "her answers under oath in front of the oversight committee left Republicans and even some Democrats convinced she either knows exceptionally little about the state of her agency's cybersecurity, or she's comfortable lying about it, insisting that breaches aren't really breaches and that obviously insecure systems are secure," end quote.

Rick Howard: Seymour, in her testimony, only mentioned the initial exfiltration of tech manuals in March 2014 and nothing about the latest discoveries. She also lied under oath about the OPM response. She told the committee that OPM had purchased the cipher tool and that they were running it in a quarantine environment. They were really running it on the production network.

Rick Howard: She also testified that the manuals stolen in March 2014 were merely outdated security documents when, in fact, they were mostly current security architecture documents. At the end of the month, 30 June, OPM finally purchased the CylancePROTECT product a day before the trial period was set to expire. They were in trial mode the entire time. Cylance didn't actually receive payment for months. OPM deployed the CylancePROTECT product on over 10,000 endpoints and found nearly one piece of malware for every five devices.

Rick Howard: On 9 July 2015, OPM issued a press release confirming 21.5 million records were compromised. The very next day, Director Archuleta resigned, and in February 2016, Donna Seymour resigned. According to The Washington Post's Ellen Nakashima, quote, "the vast majority of those affected by the Deep Panda attack - 21.5 million people - were included in an OPM repository of security clearance files. At least 4.2 million people were affected by the breach of a separate database containing personnel records, including Social Security numbers, job assignments and performance evaluations," end quote.

Rick Howard: James Comey, the FBI director at the time, said, quote, "it is a very big deal from a national security perspective and from a counterintelligence perspective. It's a treasure trove of information about everybody who has worked for, tried to work for or works for the United States government," end quote.

Rick Howard: The NSA Senior Counsel Joel Brenner said, quote, "this is crown jewels material, a gold mine for a foreign intelligence service. This is not the end of American human intelligence, but it's a significant blow," end quote.

Rick Howard: And finally, former director of the CIA Michael Hayden said OPM data, quote, "remains a treasure trove of information that is available to the Chinese until the people represented by the information age off. There's no fixing it," end quote.

Rick Howard: The Deep Panda compromise of OPM's clearance information coupled with the Anthem attacks that took place immediately after might be the largest and longest-lasting one-two cyber espionage punch known to the public against any known country. The vast amounts of data collected, plus the longevity of it - over 50 years, since that's how long it will take for all individuals caught in the net, like me, to age out of the government servers. This will be useful for many, many years to come.

(SOUNDBITE OF ARCHIVED RECORDING)

Bear Bryant: Now, listen. Let's just make it perfect. Let's just make it perfect. We're behind. They're all fired up. We got class. We're going to fight it out. We got class, and I know we got it. Now, what we got to do? First place, our defense has got to go out there and take the ball. Our defense hasn't been taking the ball. Then when we get the ball, we've got to have 11 people - 11 people who's just going to do their job, whatever it is - that's going to do their job and try to score every time you get the football.

Rick Howard: That was Bear Bryant, head coach of the University of Alabama football team and considered by many to be the greatest college football coach of all time, giving a halftime speech to his team in 1967, basically a hotwash in order to set a course for his team in the second half. So in a way, this is my version of a Bear Bryant review. And it's easy to Monday morning quarterback what the OPM leadership should have done over the years to prevent the success of the Deep Panda espionage operation.

Rick Howard: Before I pile on, I just want to say that OPM's leadership, Director Katherine Archuleta, CIO Donna Seymour and many others, made a risk assessment. They looked at what their own inspector general told them about the state of OPM's security posture and made a call. They decided that the risk was acceptable compared to the - all the other risks that they were dealing with. This is what leaders do. They make risk calls. It's why we pay them the big bucks. In this case, they got it completely wrong.

Rick Howard: I've said many times on this show that in my younger days, when the leadership didn't approve some grand plan of mine, I blamed the leadership for being naive and uninformed or incapable of understanding the complexity of my security world. In hindsight, that was just immaturity and hubris talking. What really happened was I didn't convince them that the risk I was talking about was more important than some of those other business risks they thought had a higher priority. When I think back to those discussions, I have to admit that, at least some of those times, the business leaders were right. Back then, I didn't have the tools to communicate with any authority or precision what that exact risk to the business was. This is why on this podcast, when I talk about cybersecurity first principles, risk forecasting as a strategy is as important as zero trust, intrusion kill chain prevention and resilience.

Rick Howard: So let's first talk about forecasting risk for OPM prior to the first Deep Panda breach in 2013. This one's pretty easy. OPM had no security team and no prevention or detection tools in place before the breach. There is no way that they could have noticed activity from any known adversary groups across the intrusion kill chain at that time, let alone the Chinese. They had nobody watching. And even if they did, they weren't collecting any telemetry from their endpoints and networking nodes. And even if they were, they had no tools in place to detect cyber bad guy behavior across the kill chain. After all the public intelligence about Chinese cyber operations from the early 2000s to the OPM breach, OPM leadership had refused all upgrades. They were essentially blind. When they finally installed their first tool after the fact, the Cylance product, as the congressional report said - it lit up like a Christmas tree.

Rick Howard: In terms of zero trust, they were architecturally in a better position. The OPM IT team had placed a jump server between the day-to-day OPM operations and the crown jewel data for employee and military background checks. That's the good news. The bad news is that they weren't watching it. They didn't know that Deep Panda installed software on it, PlugX, and that somebody was storing .ZIP and .RAR files somewhere on the sensitive network. They definitely didn't notice 21 million records going through the jump server and out the back door to the internet.

Rick Howard: Even if all of that were rock solid, OPM had no zero trust controls in place for their contractors - USIS, KeyPoint and CACI - to restrict their permissions. In hindsight, those contractors should be allowed to write to the OPM database but not read any records they didn't create. If they did need to read other records or change records once submitted, some secondary OPM controls should have been in place to check for legitimacy. The contractors definitely shouldn't have been allowed to copy data out of the OPM network, and they also shouldn't have been allowed to store data on their own networks for any length of time.

Rick Howard: For resilience, OPM had no incident response plan - no crisis plan at all. From reading through the congressional record, you get the sense that they were making it up as they were going. Their decision to monitor the adversary when they first noticed them and not to eradicate them when they had no real way to do that was a huge blunder. If they had reacted immediately, they would have had an opportunity window where they might have prevented the exfiltration of 20 million records. The first step should have been to call in the FBI. OPM had no resources to reject a nation-state threat like this, but the FBI did.

Rick Howard: Before the OPM breach, after years and years of negative cybersecurity report cards from her own IG, Director Archuleta should have at least had the FBI on speed dial. In response to the sensitive data she was protecting, she should have collaborated with the FBI on the crisis plan before anything happened. Now, Deep Panda's intent was not to destroy. They were stealing. A robust backup plan wouldn't have helped here. That said, OPM didn't have one. In fact, when the Deep Panda attack started, OPM technicians weren't even sure where all the copies of the data resided on the OPM networks and in their contractor networks.

Rick Howard: In terms of encryption, it was nonexistent. How OPM decided to store this kind of sensitive data in a non-encrypted form is a mystery and a major failure in resiliency and zero trust planning. If I were doing this analysis before March 2013 and before Deep Panda had any success, I would have told Director Archuleta that OPM was a prime candidate for a ransomware attack, let alone a target for a major cyber-espionage operation. I would have told her that there is a hundred percent chance that some bad guy would penetrate the OPM networks in the next three years. But as I have said many times on this podcast, not all hacks are material to the business. In fact, most of them aren't. In terms of OPM, the material data - the data they'd have stolen, destroyed or manipulated, would have had a major impact on not just OPM, but the entire U.S. government - is the background check data that OPM was the officially assigned caretaker for.

Rick Howard: From the congressional hearings on the matter, it was clear that Director Archuleta didn't know that. In my risk forecast to her before the breach, I would have told her that there is a 95% chance that some foreign actor - probably Russia, China, North Korea or Iran - would gain access to that material in the next three years. The only thing stopping them would be their own bureaucracy and set of priorities. Nothing OPM is doing would deter them in the slightest.

Rick Howard: As I said, it's easy to Monday morning quarterback massive failures in cybersecurity prevention. The OPM case is like shooting fish in a barrel and, admittedly, I'm still a bit angry that this happened. I'm an old military retiree at this point, and my records got scooped up with the rest of the 20 million records. The credit check service offered by OPM to all impacted personnel after the incident as an appeasement doesn't seem quite adequate for the enormity of the failure. So if you notice a little harshness in my presentation on this material, I'm not going to deny it.

Rick Howard: But for all network defenders during the heat of the battle, it's tough to take a beat and reflect on what could be done better next time. This is why I'm advocating for cybersecurity sand table exercises to become a staple for network defender best practice. When there isn't a crisis afoot and you can take a few moments to analyze what happened on both sides, you can learn quite a bit, just like I did while I was still serving in the active Army, participating in hotwashes after a field exercise, and just like Tom Brady did to prepare for every future football game. Replaying the exercise or watching game film can solidify in your mind what needs to be done before the next crisis.

Rick Howard: And that's a wrap. As always, if you agree or disagree with anything I have said, hit me up on LinkedIn or Twitter, and we can continue the conversation there or, if you prefer, drop a line to csop@thecyberwire.com. That's csop@thecyberwire.com. And if you have any questions you would like us to answer here at "CSO Perspectives," send a note to the same email address and we will try to address them in the show. Next week, we will be talking about vulnerability management and how it can age your zero trust strategy. You don't want to miss that.

Rick Howard: The CyberWire's "CSO Perspectives" is edited by John Petrik and executive produced by Peter Kilpe. Our theme song is by Blue Dot Sessions, remixed by the insanely talented Elliott Peltzman, who also does the show's mixing, sound design and original score. And I am Rick Howard. Thanks for listening.