A generation ahead? Not by 2030.

By 2030, the US will no longer be able to assume technological superiority. That was a principal conclusion of the Institute of Land Warfare Contemporary Military Forum's panel on " Threats in the 2030 Operating Environment." Led by the US Army's senior intelligence officer, Lieutenant General Robert P. Ashley, Jr. (Deputy Chief of Staff, G-2, United States Army) the panel included military officers and political scientists with particular expertise in geopolitics and security affairs. Their consensus was that the world in 2030 would be more multipolar than it is today, that the US-led institutions that have sustained the post-World War Two order would come under increased stress (which they may prove unable to meet), and that the US assumption that it would remain a technological generation ahead of its adversaries (an assumption "baked into US strategy," as panelist Peter Singer put it) would be proven false.

In addition to General Ashley, the panel included Brigadier General Peter L. Jones (Commandant, United States Army Infantry School and United States Army Maneuver Center of Excellence), Stephen D. Biddle (Adjunct Senior Fellow, Defense Policy, Council on Foreign Relations and Professor of Political Science and International Affairs at the George Washington University), Peter Brookes (Senior Fellow, National Security Affairs at the Heritage Foundation), Kathleen H. Hicks (Senior Vice President, Kissinger Chair and Director, International Security Program, at the Center for Strategic and International Studies), and Peter W. Singer (Strategist at the New America Foundation and an editor at Popular Science Magazine). We note at the outset that all the panelists were appropriately modest about the certainty of their predictions—confident, but clearly recognizing the inevitability of surprise. So read what follows without alarmism, but with due consideration and at least a willing suspension of disbelief.

Mission continuity amid environmental change.

Dr. Hicks opened with an account of how the Army's operational environment could be expected to change over the next fifteen years. She thinks the basic mission sets would remain constant, but that the environment would change significantly. The US will remain the world's dominant power through at least 2025, but she sees the world becoming increasingly multipolar. China is rising, and, while in her view Russia is declining, that country is doing so "with the intention to go out with a bang."

A significant source of uncertainty, in her view, is the increasing stress under which the US-led institutions (which have done much to sustain the international order since World War Two) find themselves. It's not clear that they can adapt. There's some cause for guarded optimism—NATO, in Hicks's view, has done reasonably well post-Crimea, as has the UN—but their long-term survival is very much in question. What might take their place is unknown.

Technological style and technological change.

With his customary and well-known facility with PowerPoint, Dr. Singer began by pointing out that the American style in military technology is build the "Pontiac Aztecs of war." That is, it's to produce the ugly, multipurpose system that does many things, none of them well. Our assumption that we'll be a technological generation ahead of our adversaries has been, Singer said, "baked into our strategy." We assume and overmatch that won't last. Theft of intellectual property, advanced research and development by nation-state adversaries, and the fact that much cutting-edge technology is now readily available off-the-shelf to state and non-state actors, are combining to erode American technological overmatch.

Our systems are now vulnerable to digitally game-changing technology. We can, Singer said, expect to see a convergence of new technologies that will transform military operations as the tank and machine gun did in the early 20th Century. We should expect to see, and already are seeing, a revolution in hardware, especially in robotics—robots are now in the hands of some eighty-six nations, and in those of an unknown number of non-state actors ("from ISIS to me," as Singer put it). "Ubiquitous sensors, with data sifted by artificial intelligence," are redefining the OODA loop. We're beginning to see what Singer called "waveware"—weapons that use energy itself (lasers, railguns, etc.) and 3D printing is already appearing in operational theaters. Finally, human performance modification is likely to have enormous implications for force generation, unit lethality, and soldier performance.

How will the Army deal with these simultaneous historic shifts? They represent, together, a convergence of technologies similar to the convergence of the then new tank, radio, and combat aircraft that took the form of the Second World War's Blitzkieg.

Our next conflicts will be multi-domain, and that fact alone makes the new environment challenging to the Army, Singer claimed. The US last fought a peer at sea or in the air over seventy years ago. The US Army was last bombed by an enemy air force in Laos, during the war in Indochina, when a unit was hit by improvised North Vietnamese bombers. Today, every actor in Syria and Iraq, is operating drones. We're also "gearing up to fight in space and cyberspace, places we've never fought before."

Asymmetric warfare will look very different in the new environment, Singer argued. It will become warfare in which the enemy turns your strengths into weaknesses. How will we redefine asymmetric warfare, in which the adversary turns your strengths into weaknesses? The Army will need to think through its organization and doctrine if it's to succeed in the coming multi-domain environment.

Great power competition is back.

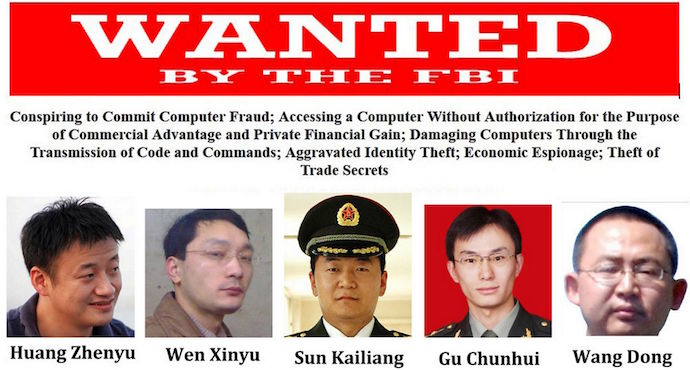

Industrial espionage will, ILW panelists said, erode the US technological edge over its competitors. The wanted poster shows officers of China's Peoples Liberation Army who were indicted for theft of US intellectual property. Photo by FBI

Industrial espionage will, ILW panelists said, erode the US technological edge over its competitors. The wanted poster shows officers of China's Peoples Liberation Army who were indicted for theft of US intellectual property. Photo by FBI

Great power competition is back, as both Hicks and Singer observed. We're engaged in a Cold War with Russia, and in the Asia-Pacific region we're in a seldom-recognized arms race with China. The formerly unthinkable war between great powers is thinkable once more, Singer said. We might see it start through deliberate choice, alliance entanglements, or even accidents.

Peter Brookes offered an account of competition from China. The Sino-US relationship is in bad shape, he said, and the balance of power in Asia is shifting in China's favor. Superpower competition the US is very much in the cards. "China, with its potential, will be our biggest strategic challenge." Brookes noted that it's first in population, second (and soon to be first) in economy, and second in defense spending (which is growing at an annual rate of 10%). It's also the greatest consumer of energy and commodities.

Strategically, Brookes said, China wants to return to a position of strength and respect after what it regards as a century and a half of humiliation. It wants to recover what it considers lost territories, not only eventually Taiwan, but also a million square miles of the South China Sea. It wants to retain the primacy of Chinese Communist Party. And above all, he said, China wants to replace the US as the dominant power in, first, Asia and the Western Pacific, and ultimately globally.

China is engaged in a significant military build-up. They're committed to research and development, and to developing the technical and scientific workforce needed to sustain that R&D. They're simultaneously professionalizing their armed forces as they downsize them from the mass armies of American historical memory. Brookes reviewed several instances of modernization. From the President on down, Chinese leadership is pushing realistic combat and joint warfare exercises. They have a bluewater navy, and they're building an indigenous aircraft carrier (ultimately they'll probably build at least four such decks). Nor is naval construction confined to carriers—they have, according to Brookes, the world's most active warship building program. Their first nuclear ballistic missile submarine's deterrence patrol is expected this year. And, of course, "We're well aware of their cyber capabilities."

China's not a "ten-foot-tall giant"—not yet—but as Brookes said, "It aspires to be you, the American military. People talk about a rising China. China's already arisen."

China isn't the only peer competitor: Russia is the more proximate threat. Brookes agreed with Hicks that Russia "knows it's in trouble." It's a revanchist power (consider President Putin's famous characterization of the collapse of the Soviet Union as the greatest geopolitical tragedy of the Twentieth Century) that has always needed $125/barrel oil. They will take risks where they see weakness.

According to Singer, Russia is being forced into the unwelcome position of being China's junior partner as its only way of staying globally relevant. Biddle characterized Russia's challenge as coping with long-term decline and short-term opportunity.

Great powers apart, there are also some challenging regional powers on the rise, Iran among them. Hicks thought the long-term prospects for Iran very unclear, but that a threat from that direction will persist, especially in cyberspace. Iran faces many internal challenges, accommodating a growing middle class, for one, and regional challenges brought about by the failure of neighboring Arab states and enduring sectarian rivalry with Saudi Arabia. Biddle characterized Iran as an "ambitious regional power that responds rationally to incentives." Iran could wind up either ascendant or destabilized; its political dynamics are too complex for confident prediction.

Real, but limited, threats are the toughest to handle.

"How do we deal with threats to American interests that are real but limited?" This was the question Dr. Biddle posed at the Forum. He reviewed a list of such limited interests, mostly in Southwest Asia, North Africa, and Eastern Europe. We care about events in these places, but we don't care enough to send 100,000 US troops. Yet if we wash our hands, we sacrifice interests that, while limited, are still very real.

This Biddle sees as a genuine dilemma, and there is no easy resolution to be had by grasping one of the dilemma's two horns, or of slipping between them. Limited interests set up "a pull toward a broad class of middle options," he said. "You end up losing the interest at stake, but at considerable expense." In most such cases of limited interests, the US has to rely on somebody else, and so must deal with a systemic problem of interest mismatch. "Good Clausewitzians know that war is a means to a political end," he said. "One ought to be drawn to the question of what the actors are trying to achieve, politically, by killing people."

We rarely provide security force assistance in countries like Switzerland or Britain, Biddle pointed out. Such countries have strong, mature institutions for resolving internal conflicts. Instead, where we provide security assistance, "our partner is probably a weakly institutionalized society whose ability to adjudicate conflicts among elites is limited." In such societies, violence, not lawsuits, adjudicate conflicts. A requirement for political order is what political scientists call the maintenance of a double balance: the balance of economic assets extracted by elites should roughly proportional to competing elites' capacity for violence.

The biggest source of potential violence in the countries we tend to engage with is a combination of the police and the army. Elites worry primarily about internal threats, and so they tend to systematically discount the value of the assistance the US provides. Elites use cronies and corruption systematically to prevent violence by maintaining balance.

Since the US conceives threats as principally external, our interests are not aligned with our partners. "This makes mission creep no accident," Biddle said. "It's an expected consequence of interest misalignment." He advised understanding our engagement with weakly institutionalized partners not as apolitical capacity building, but as an inherently political problem. Our assistance should be a tool to give incentives for political elites to align themselves with our interests. And such leverage comes from conditionality, which must be credible to be believed. "Assistance must be divisible and flexible, so it can be turned on and off," Biddle argued. If the objective is exit, that's easy to do, but the reality is that the US needs to stay long enough to create leverage.

Hybrid warfare and information operations.

Singer had observed earlier that the move to social media is another major technological and cultural shift. Every conflict actor is online. Every act of violence is now talked about online, often in realtime. "It's hard to keep secrets, but we're also seeing the truth being buried in a sea of lies."

This is a feature of hybrid warfare, or, to associate it with its most accomplished practitioner, what General Jones characterized "Russian New Generation Warfare." This represents an approach to conflict that blurs the line between war and peace. "We've seen precision massed fires, irregular forces, from our point of view questionable munitions (like thermobarics), and information operations in Ukraine." What haven't we seen, yet? A lot, he thinks. But the contest in the information environment is going on now.

Hicks pointed out that confusion and indecisive outcomes can work for the Russians the way they don't for the US. "They're in a permanent state of operational preparation of the environment," funding political parties in Europe, energy coercion, cyber operations, and influencing the media people consume.

Russia invented information warfare, Singer said. "They don't conceive of it, as we do, in narrowly military terms." The shift in the Internet is that we're all social media distributors now. Russia and China think this a threat. They regard "spreading of false rumors" (as it's described in China) as an information attack. The goal of Russian information operations is not to make people love Russia, but rather to disrupt, and create distrust. This feels new to us, but it goes back at least as far as Stalin's day. "We've got to understand that we're being manipulated," Singer said. "Our democracy itself is under information attack."