If It's Smart, It's Vulnerable: a Conversation with Mikko Hyppönen

Perry Carpenter: Hi. I'm Perry Carpenter, and you're listening to "8th Layer Insights."

Perry Carpenter: If you've been following the show for a while, you'll know that each episode I do is a bit different, from episodes that explore a single topic and feature multiple experts, to highly experimental shows that blend information and entertainment, to episodes where I put the spotlight on a single interview. And this is one of those episodes. My guest today is Mikko Hypponen, and he's a fascinating guy. I've been following Mikko for the majority of my career and, while I'm sure he doesn't remember it, the first time I spoke to Mikko was way back in 2007 for a blog that I was writing at the time. Well, since that time, the world has changed a lot. I mean, 2007 was the year when Steve Jobs gave the iPhone to the world. And just three years later, Apple released the first-generation iPad. In one sense, those innovations seem like they've been with us forever, and yet in another, they still seem really recent. And it feels like these types of innovations from our recent past have just now unlocked entire worlds of new possibilities for how we work and how we play, how we think and how we live.

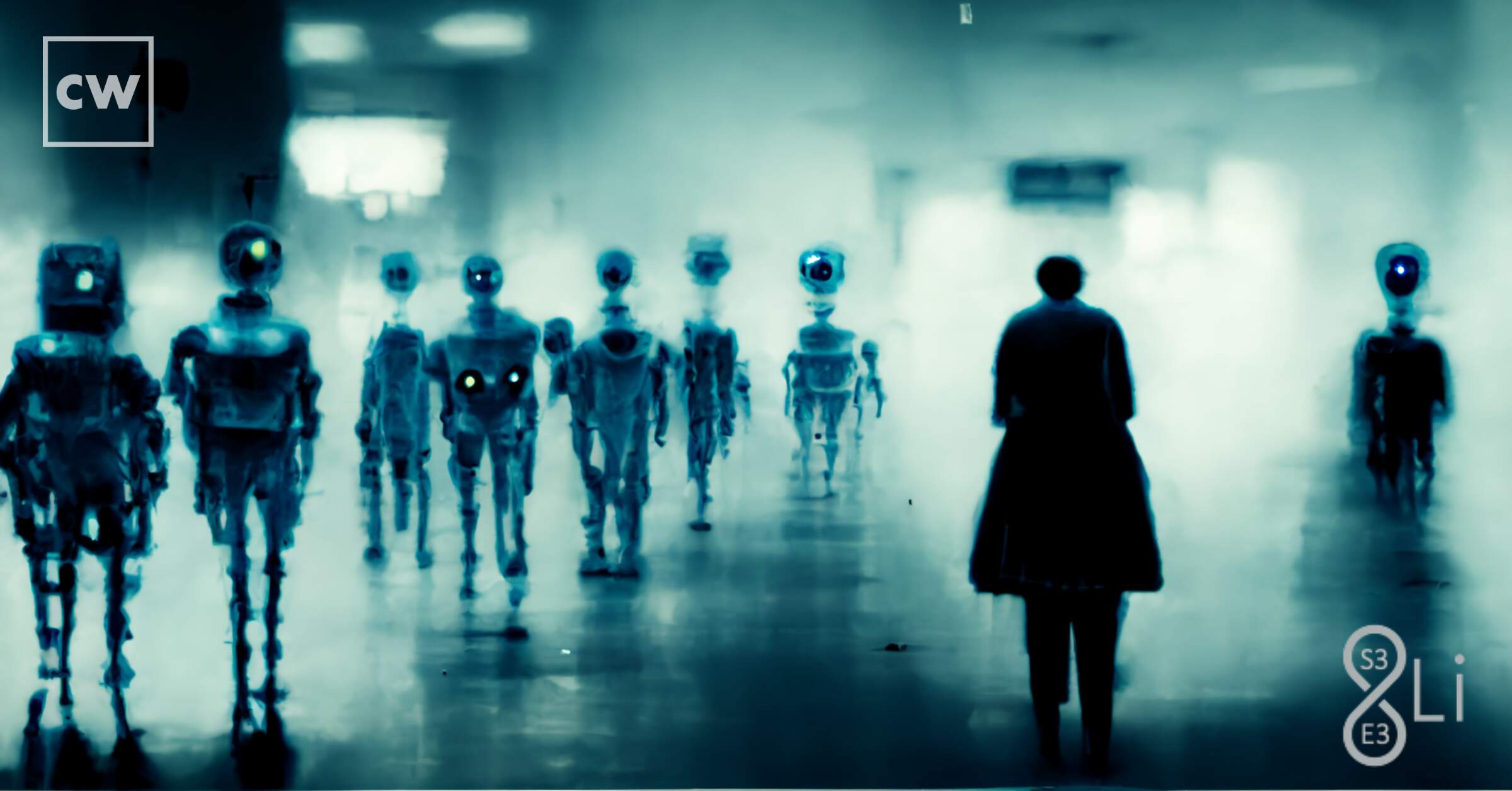

Perry Carpenter: Since that time, we've been increasingly seeing and hearing about the proliferation of all these so-called smart devices and the Internet of Things. From smartphones to smart TVs to connected health care systems to watches and toasters and more, we know that the proliferation of connected devices we see today is only a fraction of what's to come. In fact, a forecast by IDC estimates that in 2025, there will be 41.6 billion IoT devices capable of generating 79.4 zettabytes of data. That's big. I mean, that's amazing. But because we also have to put on our cybersecurity-colored glasses, I also have to say that's a bit scary. Neil MacDonald, one of my favorite co-workers from back at my time at Gartner, used to say any time you see the phrase smart device, replace it with the phrase surveillance device. I'll let that settle in for just a minute. Any time you see the phrase smart device, replace it with the phrase surveillance device. And now, let's add to that. Today's guest, Mikko Hypponen, has another saying. Mikko says...

Mikko Hypponen: If it's smart, it's vulnerable.

Perry Carpenter: If it's smart, it's vulnerable. We'll hear more from Mikko after this. Welcome to "8th Layer Insights." This podcast is a multidisciplinary exploration into the complexities of human nature and how those complexities impact everything - from why we think the things that we think, to why we do the things that we do and how we can all make better decisions every day. This is "8th Layer Insights" - Season Three, Episode Three. I'm Perry Carpenter. We'll be right back after this message.

Perry Carpenter: Welcome back. What you are about to hear is a fairly wide-ranging conversation that I had with Mikko just last week. I was super happy to catch up with Mikko because he just released his new book titled "If It's Smart, It's Vulnerable." In our discussion, we touch on the book, and we also touch on a few current hot topics, like ransomware. And we get Mikko's thoughts about the future of cybersecurity and society. And as with most of my single-person episodes, I'm keeping the editing and sound design to a minimum so that the focus stays on the person rather than the production. So with that, let's hear from Mikko.

Mikko Hypponen: My name is Mikko Hypponen. I am the chief research officer for WithSecure and the principal research adviser for F-Secure. And these are the two companies I've worked with all my life. I started in this industry in 1991, and I've been spending the last 31 years hunting hackers around the world.

Perry Carpenter: Amazing. OK. So let's get straight into the book. I noticed on page 130 that the title of the book is actually a law that you've named after yourself. It's the whole if it is smart, it is vulnerable. Can you give us a little bit of a background on what prompted you to write the book, the method that you used - because you trace a lot of history and then you project into the future - and then the thing that you want people to remember at the very end as they close it?

Mikko Hypponen: The idea behind the whole book project was to distill the things that I've learned throughout my career. And I really wanted to get the readers to understand what an unusual time we are living in the middle of right now. You see, when you're living in the middle of a revolution, it's kind of hard to see the revolution because you're living in the middle of it. But it's obvious, if you think about it in the longer-time horizons, that we will be forever remembered as the first generation in mankind's history which went online. All of this just happened to happen during our lifetime. But before our time, we were living offline, and internet will be part of mankind's future forever.

Perry Carpenter: As you're tracing this history and reminding us of how far we've come, what are the things that stood out to you? What are the inflection points that you really wanted to communicate well?

Mikko Hypponen: Well, the beginnings, the 1990s, were such an innocent time when you think about it now. We were fighting teenage boys which were writing viruses for fun. And it seems almost laughable now that we had serious problems with these viruses, which did require humans to carry them around on floppy disks. But they were a big problem at their time. Of course, the real big problems then started with email, the web and internet connectivity, and soon after with mobile phones. But I think the key year in for-profit moneymaking malware writing was 2003. That's when we started seeing organized online crime gangs starting to rise. And we started seeing more and more money being made with malware. And, of course, today, almost all malware we find, almost all of the attacks and hacks we see, are being made to make money. But that's where it really started. So that was 19 years ago. And the other key year was 2010. That's the year of Stuxnet. That's when Stuxnet was found. And that's such a key year for nation-state activity and for government-sponsored cyber sabotage and also paved the way for cyberwar, which is something we are now seeing, especially right now with the war in Ukraine. It's quite clear that cyberwar is a real thing.

Perry Carpenter: So I want to rabbit trail there in just a minute. But before we get there, I'd like your thoughts on - and you're probably tired of talking about it - but ransomware as being one of these things that kind of pull together so many threads about what makes an organization vulnerable, even the psychological threads behind that. But where do you see ransomware sitting now, and then where do you see ransomware going in the future?

Mikko Hypponen: Ransomware capitalizes on such an old idea that criminal hackers have been using, where the idea simply is that you steal valuable information and then you sell that information to the highest bidder. The real innovation here was that the highest bidder in many, many cases is the original owner of the information. If you're able to lock organizations out of their own data, some of them will pay money to get the information back. And, of course, as we've seen over the last couple years, companies also pay money to make sure the information isn't leaked online. And ransomware really exploded with Bitcoin. It was a problem already before cryptocurrencies, but the fact that criminals can use untrackable (ph) currencies for the ransom payments really made this explode. And this will going to grow. It is a huge problem. Together with BEC problems, it's the biggest moneymaker used by online crime gangs. But I think we've only seen the beginning. I think it's going to get worse before it gets better because there's companies paying the ransom. As long as these ransomware gangs are making millions and millions with their attacks, it's only going to be more gangs, more attacks, more victims. It's not going to get better anytime soon.

Perry Carpenter: When you talk about it not getting better, do you see different versions of it, or is it more of the same? I mean, over the past few years, we've talked about ransomware - the way that it was first kind of hit the scene and then, like, double extortion, triple extortion, quadruple extortion, all the different ways that they kind of pile on the pressure to make this work. Where do you think this goes next?

Mikko Hypponen: I don't see any big shift happening right now. The techniques they have at hand at the moment seem to work fine. Why would the attackers change their tactics when they're making so much money with their tactics right now? It's really hard for companies to avoid the problems which cannot be fixed by backups. The early single-step ransomware where they simply encrypted your files - I mean, it was easy enough to just make sure your backups are good enough and frequent enough and quick enough to restore that even if you get hit by ransomware, who cares? But now, with these multiple mechanisms where they run the leak sites and not only threaten, but actually do follow their threat of leaking the information if you don't pay, that's hard to solve. And I know this because I've spoken with many companies where my advice and our advice was not to pay the ransom, and they ended up paying the ransom anyway. And it is understandable. A very typical reason why executives in a victim organization make the decision that they will pay money to criminals is not about losing, like, business plans or pricing information or patent applications. They could live with all of that. What typically - I mean, example of what makes them decide to pay the ransom is that they realize that if their email archives are leaked online, it includes all kinds of confidential personal information - for example, their own employees exchanging emails with the corporate health care about private health issues.

Perry Carpenter: Yeah.

Mikko Hypponen: And when they realize that that's going to be on the public internet, they simply can't do it. And the only way they can avoid it is by paying money to criminals. Another great illustration on how bad and how difficult these choices can be is that we know of at least two cases where law enforcement agencies have been hit by ransomware, and they ended up paying the ransom. So we have cops paying money...

Perry Carpenter: Yeah.

Mikko Hypponen: ...To criminals. That's how bad it is.

Perry Carpenter: I'd really like to get your perspective then because our advice, like yours, is don't pay. But we do empathize with people that end up paying. And then we see kind of a regulatory move to say if you pay, then, you know, you're kind of not in the - you're not in the right in that. You're - we may even fine you on top of that. So how do we try to solve for this as an industry when we all acknowledge the fact that we kind of live in the mental space of the victim and we understand why they would have to pay, and yet we know that it is the fact that we do pay that continues to incite the criminals to do this more?

Mikko Hypponen: It is a game of cat and mouse. Whatever new safeguards we try to throw out there to make it harder for criminals to do ransomware attacks, they'll just find ways around them. Or they'll just find easier targets. The problem is, the attackers go after the low-hanging fruit, and the internet is like a massive garden full of low-hanging fruits.

Perry Carpenter: Yeah.

Mikko Hypponen: If we provide guidance to companies and they're able to secure their data better so they don't get hit, that's fine for those companies. But there's a thousand other companies which are still vulnerable. And the best way to really see this is to browse through the leak site for LockBit or Alpha or any of the big ransomware gangs and just look at the companies, look at the victim companies, because there's such a massive variety from all walks of life, all industries, big and small, from all countries. Like, right next to each other, you have a furniture outlet from Denmark, then you have a meat cutting company from Mexico, and then you have a telecommunications specialist company from Tokyo. Like, the variety is so huge, and it really opens your eyes to how crime has changed.

Perry Carpenter: Yeah.

Mikko Hypponen: Before the internet, we were fighting local crime. Before the internet, if you or your company became a victim of a crime, it was a local criminal living in your city. Now, just browsing through these sites just underscores the point how there are no borders. And these crimes happen on the internet, which means there is no geography.

Perry Carpenter: So if you were put on the spot and somebody that could make a significant change said, Mikko, if there is a technology-based change, a process-based change, a regulation-based change or an economic-based change that we could make that would stem the tide of this, is there a bit of advice that you would give?

Mikko Hypponen: All right. Regulation. Let's think about that. Whenever industries fail in solving problems, decision-makers and politicians like to use regulation to make sure things get fixed. I've been thinking about that a lot regarding ransomware and ransomware payments and all that, and also about IoT and connected devices because that's clearly another area where regulation is often brought up. And I'm not a big fan of regulation. And actually, I'm really divided about the whole idea of making software companies liable for the problems created by their products. As a security and privacy expert, I love the idea that software companies are liable for the problems they create. Then again, as someone who gets his monthly paycheck from a software company...

Perry Carpenter: Yeah.

Mikko Hypponen: ...I hate the idea that we would be liable for bugs in our code, because we have bugs in our code. All software companies have bugs in their code. But you could argue that at least for IoT devices - especially for consumer devices, like, you know, your washing machine - we already regulate tons of things about other kinds of safety, like fire safety and electrical safety. We don't regulate anything about software safety, and maybe we should.

Perry Carpenter: OK. One more rabbit hole real quick. You talked a little bit about the fact that we see indications of cyberwar with Ukraine. Can you give a little bit of color on that?

Mikko Hypponen: Well, I'm coming to you right now from Helsinki, which means I'm three hours away from the Russian border. Finland, my home country, has had a very long and very complicated history with a very unpredictable and very big neighbor. It's the biggest country on the planet. Both my grandfathers fought the Russians in the Second World War. Yet, I was surprised in February when Russia invaded Ukraine. I really wasn't expecting that. And I have friends in Ukraine. They weren't expecting it, either. This is quite remarkable and quite strange. And the main reason why we weren't expecting land invasion was it was so obvious that Russia wasn't ready to do it, and they did it anyway.

Mikko Hypponen: And clearly we were right. Russia wasn't ready to do it. And they tried supporting their land invasion with cyberattacks. But most of the cyberactivity really happened before the invasion or in the first weeks of the invasion. The Industroyer2 attack which they tried cutting power again in Ukraine happened in April - so two months into the invasion. But I would have expected much more cyberactivity from Russia than what we've actually seen. And the best theories that I have why we haven't seen more is that the current generation of Russian generals believe cyber matters more during times of peace than during times of war. So when missiles start flying and bombs start dropping, cyber takes the back seat. And that seems to be the way they think about it.

Perry Carpenter: Let's shift gears, talk a little bit about IoT and some of the premise of if it is smart, it's vulnerable, and then talk about ways that we can frame our approach to future thinking.

Mikko Hypponen: So the Hypponen Law is, if it's smart, it's vulnerable. And I think I first said it on stage during some talk I did years ago, and it just hit the chart. People kept repeating it. And it eventually started getting repeated so much people started calling it the Hypponen Law. I believe it even has a Wikipedia page now. And it is a very simple and a very pessimistic law, but it's also true. Like, when we add functionality and connectivity into everyday devices, they become smart. But at the very same time, they also become hackable. They become vulnerable. If you take a traditional non-smart device like a wristwatch - mechanical wristwatch - it's unhackable (ph). Then when you look at smartwatches with added connectivity and added functionality, they might be hard to hack, but, of course, they are hackable. When you have connectivity into devices which run code, people will find ways to hack them, one way or another.

Mikko Hypponen: And I am worried about security of smart devices. I spend a lot of time in my book describing why they are vulnerable and how it's a hard problem to fix because the main selling point for home consumer technology is price. Like, when people buy washing machines or dishwashers or what have you in their home, they're not asking questions about cybersecurity. They're asking questions about price - like, how much is it? - which means the vendors, which invest money into making their devices more secure, get no benefit from it. Instead, they're just more expensive than their competitors, which means the worst product wins in the marketplace.

Mikko Hypponen: And even more than worrying about smart devices, I'm worrying about the near future of connected dumb devices - so not smart, but dumb devices - which means the devices where they are online, but the users don't know that they are online. So there's no functionality that the user gets from the connectivity at all. There's no app. There's no nothing. And the reason why this is going to happen - it's really not happening yet, but it will - is simply that when it's cheap enough to put any device online, the vendors will put them online because they know that data is money. For the simple reason that they want to know where their customers are, they will be putting devices like, I don't know, kitchen mixers online. Obviously, you don't need an app for your kitchen mixer, but that's going to be online one day when it's cheap enough to do that because then the kitchen mixer maker knows where their customers are. And that's valuable information because then they know where they should be marketing more.

Perry Carpenter: Yeah. So it's valuable information. It's also valuable intelligence for someone who can gather that information and a potentially valuable attack path. So can you trace a few of those trails for us?

Mikko Hypponen: Sure, sure. I absolutely agree. It's quite clear that data is being collected by both commercial interest, but also by nation-states. The biggest companies on the planet used to be oil companies. Today, the biggest companies on the planet are data companies. So it's no wonder we keep repeating the mantra that data is the new oil. You look at the billions in profit companies like Google make every quarter, and it is actually more profitable than oil business never was. However, if you were in oil business, you have to worry about oil leaks. If you're in data business, you have to worry about data leaks. And then there is the part about nation-states and the fact that governments can monitor and control their own citizens in a way which has never before been possible. And foreign nation-states can do the kind of espionage and data collecting and profiling which has never before been possible, including influence operations, including voting influence operations, as we've seen over the last 10 years. And all of this is just a flip side of the very same technology which we've been building for profiling purposes.

Mikko Hypponen: So one anecdote I mention in my book is when I was setting up the first website for our company in 1994 and we were having a discussion in our lab about how this might become a big thing. This web might be successful. There might eventually be a lot of websites and all kinds of services on this new internet. But then we were left wondering how all of that would be funded. Like, why would newspapers bring their news to the web without being able to somehow collect money from it? Or how - why would the weather report be available online if there wouldn't be a way for paying for the weather report? And, of course, we had no idea in 1994 how all of the finance in online systems and online content would be built. But we assumed that browsers would have a built-in payment button, that I would like to see tomorrow's weather forecast - click - two cents. Here's the weather forecast for you - or half a cent, something like that - micropayments. That's how we thought it's going to work. That was in 1994.

Mikko Hypponen: Now it's 2022, and we still don't have the payment button in our browsers. And instead, we ended up with this completely different way for paying for content, which is that these gorillas of the Silicon Valley profile everything about our lives, build profiles around us and then sell that information to the highest bidder. And that is the main reason why privacy died during our lifetime. And that's why I'm worried about the kind of influence operations we've seen because the information which has been collected by companies like Facebook and Google for ad purposes - when that's being bought, for example, for election campaigns, that's really dangerous 'cause the kind of information which tells what people like, what people hate - when that's used in, like, tailor-made targeting, which is completely different for every recipient, we end up with risks to our democracy which are hard to predict. And I'm worried about that.

Perry Carpenter: Yeah. I mean, just thinking back over the history that I've seen - so I think we were all around when AOL and CompuServe started. And they did kind of have that equivalent of you pay a microtransaction to get access to Time magazine or something.

Mikko Hypponen: True.

Perry Carpenter: And then we get the more democratized version of that that exists in browsers today. And people have been conditioned to believe that everything should be free to the point where if you download a game or something and there's a microtransaction in it, that people consider that evil, and they rail against it online. So how do we put the genie back in the bottle and get it to where we have more control and autonomy over our data? - because it seems to me that unless everybody does it, the water is going to run to the path of least resistance, which is going to be free for a vast majority of the population.

Mikko Hypponen: I have bad news. We are not going to put the genie back into the bottle. We've lost this fight. Privacy's dead, and we will not be able to revive it. And we will forever be remembered as the generation which killed it. You and me - we killed privacy. People live their lives online. We carry mobile phones on our persons throughout the day. We even sleep next to it. And through this technology, through mobile phones, through the internet, we get great benefits. But the trade-off is that we have no privacy, and we can be tracked from cradle to the grave. And it's not going to change. This is undoable. And it's a bit sad. But I don't see any way of reversing that.

Perry Carpenter: Yeah. I remember - I was working for a telco back when location-based services started to first become a thing. And I remember us, internally - of course, the marketing teams were very happy about it - but I remember us, internally, in the security team saying, oh, if we are now tracking people and making this data more accessible about what John Doe is doing 5 of 7 days out of the week, and then two nights a week, his phone is near this other person's phone for eight hours. Then all of a sudden, lots of inferences can come from that. I would love - without trying to be overly alarmist - if you can paint a picture of what this forsaking of privacy looks like in the smart device world.

Mikko Hypponen: Today's machine learning functions can infer things about our lives just based on data - location data, communication data, what we type, how do we use our machines. They can infer the kind of information that we might not be aware ourselves yet, that they might be able to figure out, you know, how we will be thinking about something which we haven't actually even thought about yet. Or they might simply be aware of things that no one else knows.

Mikko Hypponen: A very practical example of that is that today when you have some embarrassing or very private thing, the first party you ask about it is Google. Like, you - before you ask your friend or spouse, people Google for things. And this is quite remarkable. We volunteer the kind of private information we wouldn't tell to our spouse to a company in California. Isn't that a bit weird? But it has become the norm. And this is - I mean, we know this from our everyday lives, but it's startling how it happens everywhere. For example, law enforcement - of course, forensic examination of devices of suspects has become such a crucial part of investigations because murderers Google for things like, how do I hide the murder weapon? No joke. That's what they do. And it's such a valuable information for law enforcement, for investigations that, you know, if it applies there, it applies everywhere else as well.

Perry Carpenter: Of course, the other thing is writers also Google that because as you're trying to think about how you have your murderer in your plot hide the murder weapon, that's the first thing...

Mikko Hypponen: Is that your is that your excuse, Perry?

Perry Carpenter: Yes, that's my excuse.

Perry Carpenter: Welcome back. Before we get back into the interview with Mikko, I've got a couple quick asks for you. If you haven't yet, please go ahead and rate and leave a review in Apple Podcasts or Spotify or any of the other apps that allow you to do so. That would really help me out as I try to continue to build brand awareness and trust for the "8th Layer Insights" podcast. It would also really help me out if you recommend this show to a friend or a colleague or somebody else in your network. And that could be as easy as doing a recommendation on LinkedIn or Twitter or just sending a friend a text message right now. So I really appreciate your help with those things. Those would really help me out a lot. Thanks. And let's get back to the interview with Mikko.

Perry Carpenter: So the thing that most people will think - and they'll come in and they'll say, oh, I - it's fine for me to give this information away because it is one very small data drip in a very, very large bucket. And to somebody like Google, I'm a nobody. So what is the actual danger for the, quote-unquote, "normal citizen" that believes that they're not important enough to be vulnerable in this way?

Mikko Hypponen: It might not be a question about, do we have anything to hide? Maybe it's more a question like, do we have anything to protect? When people tell me that they're not worried about, you know, their data being available to parties like Google and Facebook because they have no secrets, what I'm hearing is that I shouldn't tell this person anything confidential because, clearly, they don't - they are not able to keep secrets. Privacy is a human right. Privacy is included in the declared human rights. And the fact that we can give it away easier than ever before is no justification for us doing it.

Mikko Hypponen: If people knowingly and willingly are doing a trade-off that they get a service in exchange of volunteering their information, that is their decision. But right now most of us are making that decision because there is no alternative. And what I mean by that is that when you take in to or use a new application or a new service, you sign up for some website, they give you this end-user license agreement. And we all know that those 30 pages of legalese contain horrible things that we wouldn't agree on. But it's not really a negotiation situation at all. You have two options - agree and use the service, disagree and don't use the service. Like, if you don't agree to Google's license agreement, you're not allowed to watch YouTube videos or to make Google searches. And you can't live without these things anymore. I know because I tried. So it's not really something we choose 'cause there is no alternative. And that's what worries me.

Perry Carpenter: In a second, I want to have you give some thoughts about the future. But I think before we do that, I've got one other question about the book. It seems like as you were tracing the history of computer security and IT, one of the tools that you used was personal stories. And I forget if it was Code Red or WannaCry, but I do remember the story about the fact that you were having to deal with this situation in the middle of what would have been a holiday for you. And so me, as a reader, I started to understand a little bit about the impact that this has on the lives of people who are trying to deal with these kinds of situations as they arise. Can you talk a little bit about that and why that was part of your decision on your approach for the book?

Mikko Hypponen: You're right. The book contains lots of stories because that's the kind of books I like to read myself. We humans like to listen to stories told by other people or like to read stories by other people. And when I was working on this book, I was thinking about the books - the best books I've read myself, the books I like to read, the kind of books I prefer. And the kind of books I really like to read are the kind of books which contain both hard facts but then stories illustrating what it really means. So that's why I tried to put in as many stories as I could into the book - going through things I've seen or cases I've worked with or stories of success, stories of failure. And that's the best feedback I've been getting on the book is that people tell me that...

Perry Carpenter: Nice.

Mikko Hypponen: ...You know, they just, you know, love the stories. Tell me more. And maybe one day I'll write another book, and I will have even more stories in that.

Perry Carpenter: Well, you know, the thing it does is I think it takes this abstract topic of security and vulnerability and all the stats, and it humanizes it - even to the point where, yeah, we're thinking about the human effects that it has on the victim in these circumstances, but also the human effects and stories that it has for somebody like you that's sitting in the middle of it reacting and having to say, how do I deal with this situation that's emerged? So, yeah, I really appreciate that. As we think about how to end this, I would love your thoughts on, as you try to project yourself into the future and think about the next big threat or the next big trends that are coming, how do you build a framework for thinking accurately about the future and being able to predict what's to come?

Mikko Hypponen: Yeah, it's not easy. I mean, forecasting the long-term future of technology is easy. I know it sounds a bit weird, but that's pretty obvious to me. It's not very useful to us because I'm speaking about the long-term future - decades into the future. And that's easy to see when you look at the longer timelines. Computers have been getting faster and faster with more and more storage and bandwidth for decades, and they've been getting cheaper and cheaper - illustrated by the fact that we're carrying iPhones in our pockets, which have the computing power of a Cray-2 supercomputer from the 1990s or even more, which is just crazy 'cause, you know, Cray-2 required a power generator, and these are running on batteries. But it's just what's happening. So the end game, based on that, will be that eventually - in 30 years or so - we will all have access to unlimited computing for free. So massively fast computers with massive memories, massive storage, unlimited bandwidth, and they are free - or almost free. That's the future where we're headed. But like I said, that's maybe too far for - to us to make anything practical on.

Mikko Hypponen: The near future - what's going to happen in the, you know, next three years or so. For years, I've been running programs inside F-Secure and now WithSecure, where we try to forecast the near future. We call this TRAP (ph) - the threat assessment process - where we try to forecast what the enemy will be doing. And it's hard. I mean, we've had success stories. We were, for example, able to point out that rootkits will become a big problem before they did. But then again, we've had, like, big mistakes. For example, we estimated mobile malware to become a real problem maybe eight years before it really happened. So we were way ahead of the real threats. But if I would have to name something right now, for the next three years, that's going to be AI. And not AI for defense, because we've been doing AI for cybersecurity for 15 years or more, but AI from the point of view of the attackers.

Perry Carpenter: So by that, are you leaning into more AI as far as profiling and building better, more personalized spear phish and then running those at scale or are you thinking about deepfakes? What aspects of AI?

Mikko Hypponen: All of those that you mentioned are possible. But I think the first steps will be much more mundane. I think they will simply optimize their existing operations to run automated, without humans in the loop. If you look at the typical malware campaign - for example, ransomware campaign - today, it's actually pretty one-sided. What I mean by that is that the attackers are, you know, manually creating new malware. Then, let's say they are sending it out over emails which contain malicious links. They create those emails and the servers where the links point to manually. And then they start spamming them out, monitoring how we, the defenders - how we react. And the reactions from security companies are largely automated. We are running all these canneries and honey nets and honeypots, which will detect these automatically and collect the samples automatically and automatically decode them and cross-reference them and build detections and test the detections and deploy the detections, which means the reactions are very fast because it's automatic. And then that creates a reaction at their end, which is manual. Humans - criminals realize, OK, we're getting blocked. Our websites are on blacklists. Our malware binaries will not run on end point. We have to modify them. And then they modify them by hand, which takes a lot of time.

Mikko Hypponen: All of that could fairly easily be replaced with automation frameworks or simple Python script or TensorFlow instance or machine learning mechanisms which would detect what we do and adjust automatically - recompile the binaries, change the code, rewrite the ransomware, register new domains, create new spam emails with similar messages. All of that could be done by a machine. And it's not done yet. We know, because it's just so slow, that it's clearly done by humans. And this will happen soon. It's going to happen in the next two years, I'm sure. And then we will see that the only thing which can stop a bad AI will be a good AI.

Perry Carpenter: If you were to decide to write a science fiction novel today that had a cybersecurity bent to it that was set 10 years in the future, what types of threats and what types of plot points would you want to bring out?

Mikko Hypponen: Oh, that's a great question. I've never written fiction of any kind, even though I read quite a bit of fiction.

Perry Carpenter: Right.

Mikko Hypponen: I think I wouldn't be able to top some of the technological science fiction that I've read. I guess my favorite in this area would be Daniel Suarez, maybe best known...

Perry Carpenter: Yeah.

Mikko Hypponen: ...for "Daemon," which is a great example on how someone like Daniel, who understands the technology, who has a technical background, who's a coder himself - when he uses his real-world knowledge to combine what could be done, what...

Perry Carpenter: Right.

Mikko Hypponen: ...Could happen in the near future. And if I would write a science fiction book, it would be something along those lines. And in "Daemon," there's a superhuman or super intelligent entity created by a coder who died and left it behind and it goes haywire. That's a great premise. I love the book. I'd probably try to clone it, something like that. Try to top it if I could, and I'm sure I couldn't.

Perry Carpenter: Oh, yeah. That was - that's, like, five or six years old at this point.

Mikko Hypponen: Yup.

Perry Carpenter: And there's not been a lot...

Mikko Hypponen: It should be happening already.

Perry Carpenter: It should. It should. And he talked about even like fMRIs and everything else. I remember it kind of bridged a lot of gaps that most people didn't think about when they thought about computer security. All right, one more thing you may or may not want to comment on. What do you think about the state of disinformation and our ability to perceive truth over the next few years?

Mikko Hypponen: When the internet came around, parents were warning their children that, you know, don't believe everything you read online. That was 25 years ago. I think today it's the parents who are the problem because, you know, the younger generation, they've grown up with the internet. They know exactly that, you know, you can't trust everything that's online and, you know, fake news and all kinds of operations and disinformation. But it's the parents who seem to be buying into all these crazy conspiracy theories and falling for all kinds of scams. That is a problem, but maybe it is a problem which will fix itself. You know, the older generation, which hasn't been brought up with the internet, who doesn't intimately understand how to live online, is going to grow old. And the next generation, well, they'll be much better equipped to handle all of this.

Perry Carpenter: And with that, thanks so much for listening. And thank you to my guest, Mikko Hypponen. As usual, you can check out the show notes for all the relevant links and references to the topics that we covered today. If you've been with me for a while and you haven't yet, please consider rating and leaving a review in Apple Podcasts, Spotify or any other platform that allows you to do so. Ratings, reviews and word-of-mouth recommendations really do help people trust that this show is worth their most valuable resource - their time. Of course, if you haven't yet, please go ahead and subscribe or follow wherever you like to get your podcasts. And if you want to connect with me, feel free to do so. You can find my contact information at the very bottom of the show notes for this episode.

Perry Carpenter: This show was written, recorded, sound designed and edited by me, Perry Carpenter. Artwork for "8th Layer Insights" is designed by Chris Machowski at ransomewear.net - that's W-E-A-R - and Mia Rune at miarune.com. The "8th Layer Insights" theme song was composed and performed by Marcos Moscat. Until next time, I'm Perry Carpenter, signing off.