Gangnam Industrial Style APT campaign targets South Korea.

Dave Bittner: [00:00:03] Hello everyone, and welcome to the CyberWire's Research Saturday. I'm Dave Bittner, and this is our weekly conversation with researchers and analysts tracking down threats and vulnerabilities, solving some of the hard problems of protecting ourselves in a rapidly evolving cyberspace. Thanks for joining us.

Dave Bittner: [00:00:23] Thanks for listening to the CyberWire's Research Saturday podcast. Today, I want to reach out to those members of our audience who are students or serve in the military. Did you know that the CyberWire has special CyberWire Pro subscription offers just for you? Well, you do now. Because of your student or military status – that's active or reserve military status – you are able to subscribe to CyberWire Pro or CyberWire Pro+ at a significant discount. That means you can unlock access to our Focus Briefings, exclusive podcasts, quarterly analyst calls, premium articles and much more. To learn more, visit thecyberwire.com/pro and click on the "Contact Us" button in the "Academic" or "Government and Military" box. That's thecyberwire.com/pro, and then click "Contact Us" in the box that applies to you, and we'll hook you up. Thanks again for listening to Research Saturday.

Dave Bittner: [00:01:18] Thanks to our sponsor, Reservoir Labs. Reservoir Labs knows that cybersecurity teams need full network visibility to discover new threats, tactics, and behaviors. This is true today more than ever. Reservoir provides solutions based on rock-solid, enterprise-class, high-speed network sensing and spectral hypergraph analytics, using advanced algorithms and mathematics to give experts an advantage, built for critical commercial and government networks. Learn more at reservoir.com/cyberwire. That's reservoir.com/cyberwire. And we thank Reservoir Labs for sponsoring Research Saturday.

Phil Neray: [00:02:02] This campaign was discovered by Section 52, which is our in-house threat intelligence team. This is a team composed of former nation-state defenders.

Dave Bittner: [00:02:13] That's Phil Neray. He's VP of IoT and Industrial Cybersecurity at CyberX. The research we're discussing today is titled, "Gangnam Industrial Style: APT Campaign Targets Korean Industrial Companies.

Phil Neray: [00:02:29] The research that we're going to talk about today was specifically done by a group of folks, including David Atch, Maayan Shaul, Gil Regev, and Ori Perez. And it's a campaign that we first started tracking in the Spring of 2019, a highly targeted spearphishing campaign that compromised more than two hundred manufacturing and other industrial firms primarily located in South Korea. So that's what led us to name the campaign "Gangnam Industrial Style."

Phil Neray: [00:03:03] One of the things that's interesting about this campaign is that it uses high-quality content to make the attachments more believable and realistic – so, to get the users to click on them and actually get the malware installed on their systems. And in that way, it's similar to the Agent Tesla campaign that was recently uncovered by Bitdefender. I'll give you some examples. The emails are requesting firms to bid on projects, so it's RFPs, RFQs. And so, in one of them, in an email that was purporting to be sent from Siemens – of course it wasn't, but it was spoofed to look like it was coming from Siemens, which is a major global industrial engineering firm – it referred to a real gasification power plant in the Czech Republic. To make it even more realistic, it included a white paper as an attachment about the project and a schematic of the power plant. In another example, in an email that was spoofed to look like it was coming from a major Japanese conglomerate, it invited the recipients to bid on a project for a power plant in Indonesia. And to make it look realistic, they included the annual report for the major Japanese conglomerate. Of course, it's an annual report that anybody could get from their website, but that's what they used to try to get the recipients to believe that it was a real offer to bid on these projects and to get them to download the zip file to their desktops.

Dave Bittner: [00:04:47] And how successful was the campaign, in your estimation?

Phil Neray: [00:04:52] Well, we were able to identify over two hundred compromised firms, based on the systems that were compromised and their domain names. Primarily located in South Korea – like, over fifty percent were located in South Korea, over fifty percent of them were in manufacturing. But we did find victims in other locations, like Thailand, Japan, Indonesia, Turkey, Germany, France, Ecuador, and the UK.

Dave Bittner: [00:05:26] And how did you go about discovering this? What was your methodology for uncovering what was going on here?

Phil Neray: [00:05:32] Yeah, so, Section 52, our in-house threat intelligence team, has developed an automated threat extraction platform, which we call "Ganymede." And it supplements the the manual work the threat intelligence analysts do all the time, but it's a much more efficient way of doing things, because Ganymede ingests data from a range of open and closed sources on the Internet and then uses specialized machine-learning algorithms that we've developed to identify industrial-themed content or IoT-themed content. And so we started seeing this, you know, based on the attachments that were about power plants, based on the names of some of the companies, like Siemens. That's how we sort of first caught onto this campaign.

Dave Bittner: [00:06:23] Well, let's walk through it together. Can you take us through exactly how the malware works?

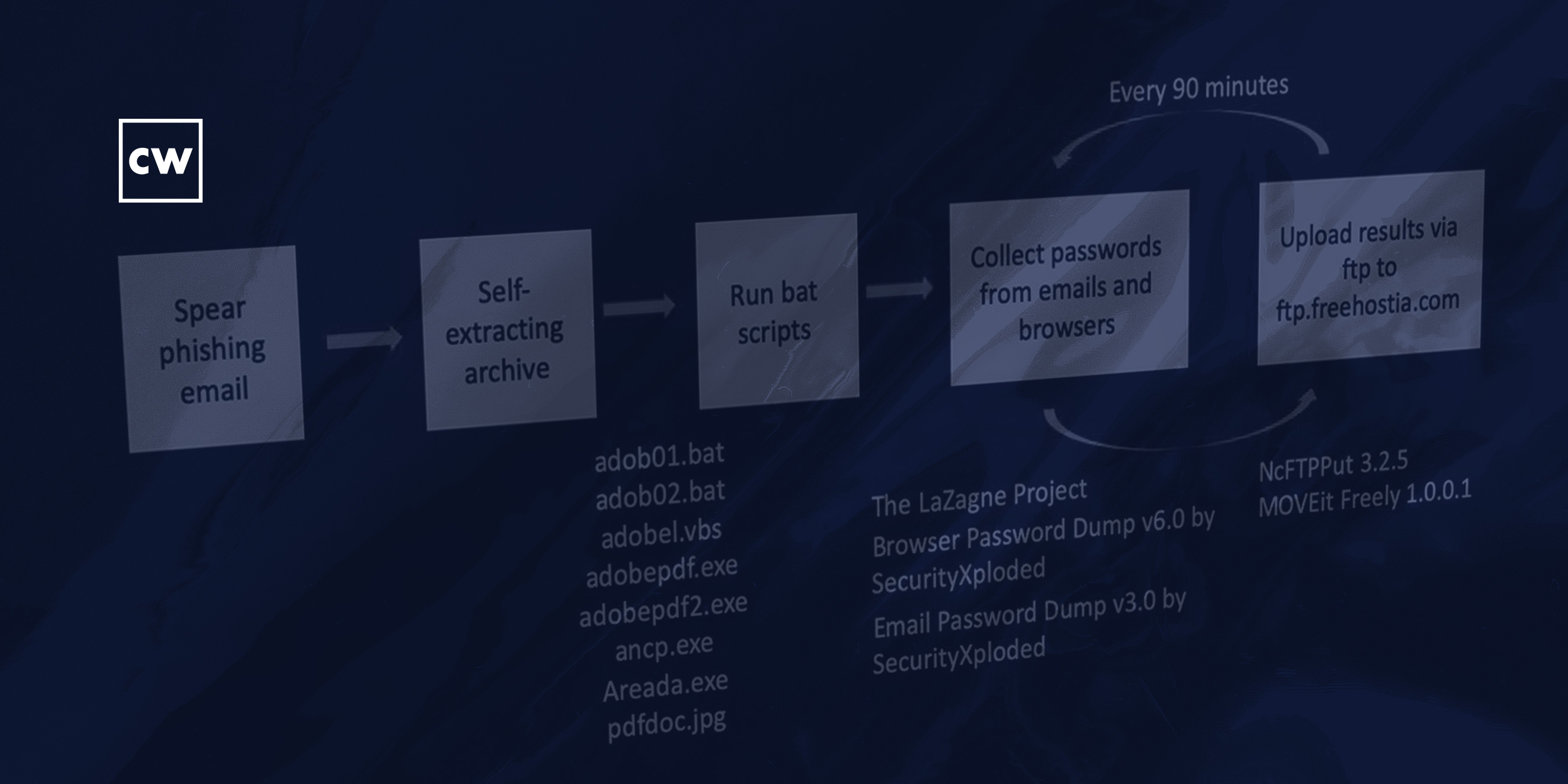

Phil Neray: [00:06:29] Yes, certainly. So, as we said, the recipient gets a spearphishing email, which appears to be very realistic. The email includes, as an attachment, a self-extracting archive, which, when unzipped, results in a number of files being downloaded to the desktop that appear also to be realistic. So, they've got names that look like Adobe files, for example. But in fact, what these files are, are a combination of batch scripts, Visual Basic scripts, some executables, that then install a number of tools, malware tools onto the user's machine. And one of the interesting things about these tools is these aren't highly sophisticated tools, they're not exploiting zero days. This is a collection of open-source tools, most of which are freely available on the Internet, that are used to grab passwords and collect files from the user's desktop. And then every ninety minutes, these tools upload the data that they've exfiltrated from the user's machine to the adversary's command-and-control server, which is located on a free hosting website just to make it harder for anybody to track who these people really are.

Dave Bittner: [00:07:56] So, in order to kick things off, to get things running, they're using a PDF file, or a file that appears to be a PDF but but actually isn't?

Phil Neray: [00:08:08] Correct. So, it has, like, a PDF icon, but it's actually a malicious executable. And then that executable in turn – or a number of executables – are really a series of scripts that were compiled using the quick batch file compiler. And then what those scripts actually do once they start running, is first they run ipconfig, which is a tool to look at all the network adapters that are on the system. They disable the Windows firewall. They start dumping passwords from the browser, passwords from email, and then they start looking for documents with specific extensions. So, the ones you'd expect, like extensions for Word and Excel. But also I found some really strange file extensions, which I had to look up, which were from, like, Czech word processors and things like that. So, a bunch of different files. And then after they've collected the files and the passwords, they upload everything to the to their FTP server – again, using a freely available tool for FTP to do it.

Dave Bittner: [00:09:18] And what do you suppose they're after here? Is it just a broad collection of anything they can grab?

Phil Neray: [00:09:25] We had a couple of hypotheses about what their true intent was. One would be to deploy ransomware into these environments, either on the corporate network side or on the industrial network side. And you can see, obviously, that if you deploy ransomware into a plant or to a firm that's running an industrial network, the cost of the downtime is high and the owners of the plant might be more willing to pay the ransom. Another hypothesis is that they are simply doing cyberespionage to collect information such as sensitive intellectual property about proprietary manufacturing designs or manufacturing processes. Or, if it's a nation-state campaign, that they're collecting information that they can then use in the future to cause some kind of disruption to these factories.

Dave Bittner: [00:10:22] Are there any indications as to who might be behind this?

Phil Neray: [00:10:26] No, we were not able to determine who would be behind it. You know, you might guess because South Korea was the target, that it would be North Korea. We don't really know. This is how I think this campaign is relevant to the Agent Tesla campaign, which was recently talked about by Bitdefender. In the sense that companies are always looking to get new business and an email that comes in saying, hey, we'd like you to bid on this project is likely to be eagerly opened by the recipient. Now, the way I think this relates to Agent Tesla is, in current times, people are even more eager to find new business. And while the Bitdefender folks had a hypothesis that the goal of the Agent Tesla campaign was to find out what countries were going to do about the OPEC deal, an alternative hypothesis would be that, given the current pandemic, companies are really desperate for business, and so they're just using this current situation opportunistically because they think people will be more willing to open these emails without doing any careful scrutiny.

Dave Bittner: [00:11:38] And what sort of recommendations do you have for folks to protect themselves against these sorts of things?

Phil Neray: [00:11:44] The recommendations that we have to protect against these types of campaigns are fairly standard. Number one, raise awareness with your employees about the dangers of clicking on emails from people you don't know or firms that you don't know. Look for spoofing in the email addresses that would indicate that even though it seems to be coming from Siemens, perhaps it's not. And then finally install continuous monitoring in your networks, both on the IT network and the industrial network, so that if any adversaries actually do compromise those networks, you can quickly spot their activity.

Phil Neray: [00:12:23] So, in the current pandemic, what we've seen from our clients that are industrial organizations worldwide is that because more workers are required to work remotely, there's been an increase in remote access to their industrial networks, either by their own employees or by third-party contractors that they hired to configure and maintain the equipment in their plants. And as a result, we think that adversaries are looking for ways to steal remote access credentials, – either from the employees or from third-party contractors – so they can also get into the plants using these remote-access methods, and hoping that they're going to be hidden in this higher volume of traffic that we're seeing now.

Phil Neray: [00:13:13] So, you know, remote access to industrial networks has always been a challenge, in that if you're not using modern methods to enable folks to get to your networks in the factory remotely, such as using VPNs, using password vaults, using two-factor authentication, there's a higher likelihood that a bad guy is going to get those credentials and get into your network without you knowing about it. But we think that in the current pandemic situation, that's become even more of an issue just because there's a much higher volume of remote access traffic to these networks.

Dave Bittner: [00:13:54] Yeah, I'm really interested in your insights there in terms of how things have changed on the ground for folks in these environments. On the OT side of the house, the operational technology side of the house, are there fewer people on-site because of the the need for folks to stay home to keep that that social distancing? Is that an issue as well?

Phil Neray: [00:14:16] Yes, absolutely. There is, in the current situation, far fewer personnel working in the plants themselves. And so, therefore, they're being asked to do their work remotely. So, that work would include monitoring the systems that are going on in the OT side of the house, configuring and maintaining the programmable logic controllers. And in fact, we've gotten requests from our clients who are now much more concerned about the risk of their industrial networks being compromised and are looking for us to be able to remotely deploy our cybersecurity solution to plants. In other words, ship an appliance or a virtual appliance to these plants, and then install it and configure it remotely so that they can monitor this increased remote access traffic and make sure that nothing bad has happened.

Dave Bittner: [00:15:11] Yeah, that's fascinating.

Phil Neray: [00:15:13] So the Gangnam Industrial Style campaign uses a type of malware called Separ – S-E-P-A-R – that has actually been around since 2013 when it was first discovered by SonicWall. But it has continuously evolved over time. And so, this is another trend that we're seeing, which is using, you know, sort of off-the-shelf, freely available tools to perform these types of campaigns, and then over time, increasing the number of tools and the types of things that they can do. So in this case, for example, they're using new tools, and compared to the most recent version of Separ that we had seen, the previous version gathered passwords but did not collect files. So they added the ability to collect sensitive files, or all kinds of files, like Word files. The second thing they did to improve on the previous version of Separ was to use auto-run to enable persistence after reboot. This is a common technique used by malware writers to ensure that after the reboot, the malware continues running. So this is, I think, also something we saw with Agent Tesla, where that malware had been around for a while, but has continuously evolved over time.

Dave Bittner: [00:16:38] Our thanks to Phil Neray from CyberX for joining us. The research we discussed was titled, "Gangnam Industrial Style: APT Campaign Targets Korean Industrial Companies." We'll have a link in the show notes.

Dave Bittner: [00:16:51] Our thanks to Reservoir Labs for sponsoring this week's Research Saturday. Don't forget, you can learn all about them at reservoir.com/cyberwire.

Dave Bittner: [00:17:00] The CyberWire Research Saturday is proudly produced in Maryland out of the startup studios of DataTribe, where they're co-building the next generation of cybersecurity teams and technologies. Our amazing CyberWire team working from home is Elliott Peltzman, Puru Prakash, Stefan Vaziri, Kelsea Bond, Tim Nodar, Joe Carrigan, Carole Theriault, Ben Yelin, Nick Veliky, Gina Johnson Bennett Moe, Chris Russell, John Petrik, Jennifer Eiben, Rick Howard, Peter Kilpe, and I'm Dave Bittner. Thanks for listening.