LockBit's contradiction on encryption speed.

Dave Bittner: Hello, everyone, and welcome to the CyberWire's "Research Saturday." I'm Dave Bittner. And this is our weekly conversation with researchers and analysts, tracking down the threats and vulnerabilities, solving some of the hard problems of protecting ourselves in a rapidly evolving cyberspace. Thanks for joining us.

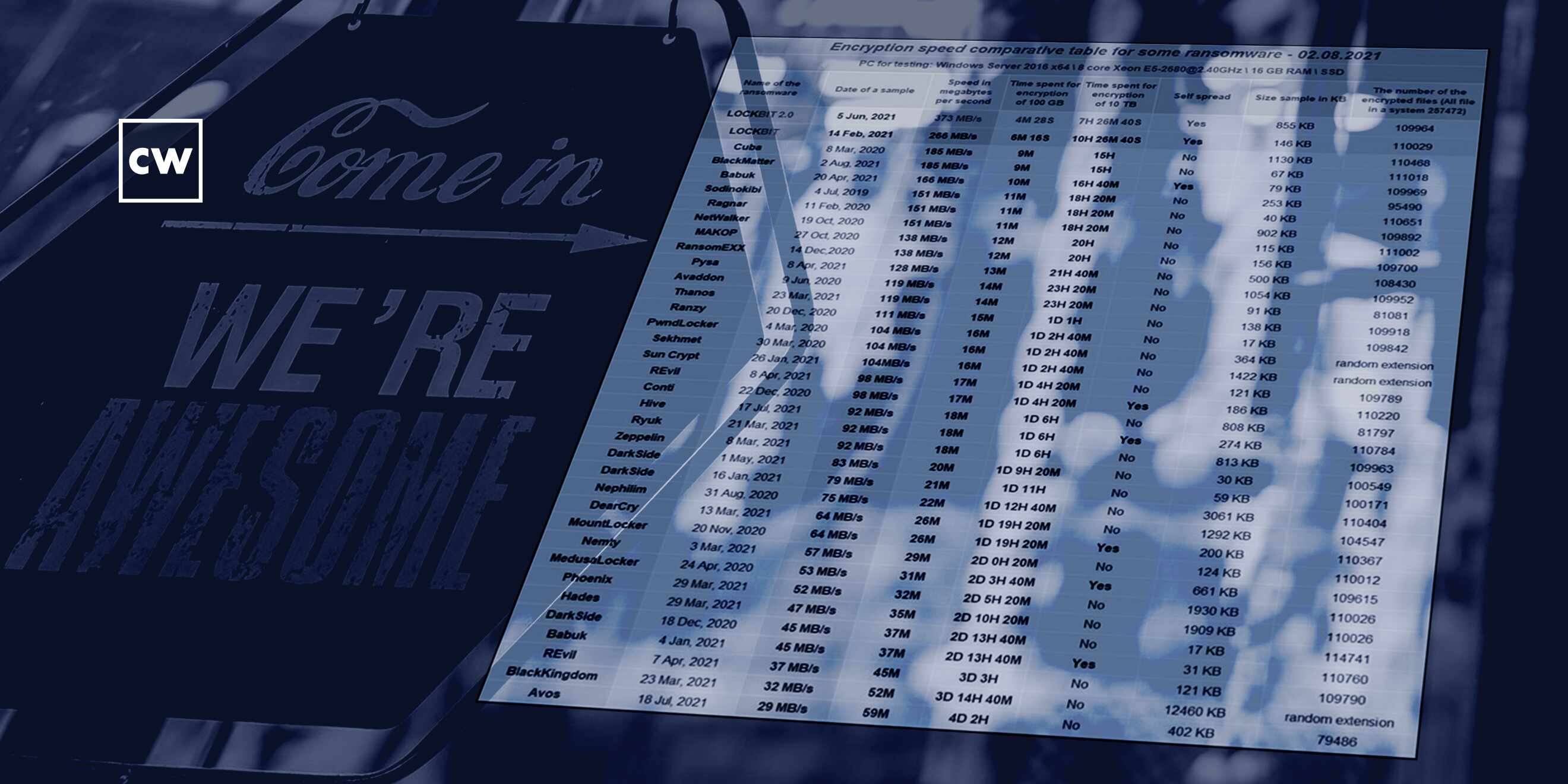

Ryan Kovar: And we had one question that we kept asking ourselves was - how fast does ransomware actually encrypt? And we couldn't really find anyone who had conclusively answered that. And the only people who had, from what we could tell, was actually the LockBit ransomware group.

Dave Bittner: That's Ryan Kovar. He's a distinguished security strategist and leader of SURGe, a blue team security research team at Splunk. The research we're discussing today is titled "Truth in Malvertising?"

Ryan Kovar: Earlier this year, one of my employees, Shannon Davis, had started looking at ransomware. And, you know, when we went through ransomware, we always do a literature review for every project that SURGe works on, and we really found that most of the work had been kind of clumped around a couple big areas, the first being ransomware groups - so working on, you know, who are these people, what are they doing, really diving into the threat actors. And we said, great, there's been a lot of work done, probably don't need to keep going into it. The second thing we found that people had been working on was around the actual way people are paid for ransomware and the motivations - you know, bitcoin or different currencies and clawing back that money. And we said, great, there's been a lot of work done there.

Ryan Kovar: And then the final part that we've seen a lot of work done on was detections. And we said, OK, that's a little bit more interesting. But what's something that hasn't been worked on? And we had one question that we kept asking ourselves was - how fast does ransomware actually encrypt? And we couldn't really find anyone who had conclusively answered that. And the only people who had, from what we could tell, was actually the LockBit ransomware group.

Dave Bittner: (Laughter).

Ryan Kovar: It turned out that they had actually written up a very nice, scientific-looking document explaining why their ransomware was so good. So we said, OK, this is super interesting. Let's put this to the side. But let's actually do our own scientific analysis. And we did that, and we released a white paper and blogs and presentations and stuff like that earlier this year. And then we came back, and we said, OK, well, let's actually look at this LockBit work. And that's how we ended up with this "Truth in Malvertising?"

Dave Bittner: Well, help me understand here. I mean, why is speed of encryption something that matters if I am someone offering a ransomware service here?

Ryan Kovar: So twofold - one, what we found was it was a advertising angle. And I found this fascinating because there's been a lot of work done - and, Dave, I know you've talked about it - just this concept that ransomware organizations are greater than just cyberattacks. They are an actual business. They have 24-by-7 help desks. You know, they have increasingly better bug bounties than many commercial organizations. And one part that we hadn't really thought about was the marketing aspect. And what this page, which was actually on their Onion Router website - so you can actually visit it - showed was that there is a move where they were seeing competition from a crowded marketplace - so, you know, Adam Smith's invisible hand is actually at work here - and they are seeing that, like, oh, man, there's a lot more ransomware groups than there used to be. People are actually selecting different ransomware services. We need a way to actually explain why our ransomware is better than others.

Ryan Kovar: And so they created this - like I said, this table which clearly showed, at least in their eyes, that their ransomware was the fastest to encrypt. And the reason that could be a value is - and actually, why we also did our primary research - was the question was - what can a network defender do once ransomware starts? And, you know, we found that it took anywhere from something like four - or 3 1/2 or 4 hours for some ransomware to execute over 100,000 files. But ransomware from LockBit might only take 4 minutes and 30 seconds. So if you're looking at this from a network defender point of view, I can't stop 4 1/2 minutes or 5 minutes. I might be able to stop some ransomware encryption in 3 hours. And I think LockBit is kind of looking at this the same angle of, if you're trying to make sure that you're selling a service that people will get their money out of, you know, faster is better. And that's what they're selling.

Dave Bittner: Right. So it's more likely that we'll be successful in encrypting the files on some - on a victim's system here before they are onto us. And that's the advantage that speed gives us.

Ryan Kovar: Correct 100%.

Dave Bittner: Yeah. So you all, I think, wisely, did not trust the marketing angle of the LockBit folks themselves and decided to dig into it. How did you go about that?

Ryan Kovar: So we had created a testing harness for our original work that was much more around the - a concept of scientific method. But we actually had most of the details there because LockBit, once again, in a surprising bit of we'll prove it to you yourself, you know, take-it-home, 30-day warranty, they actually gave a lot of evidence and details of their testing, including the ransomware samples that they tested on. So thanks to LockBit, we were able to actually take the same samples. They provided a general idea of how large of a file they had to encrypt, a hundred gigs or 10 terabytes. And they also said how many files they encrypted and the sample and the ransom - so they gave a whole bunch of evidence. So we kind of took that. We had to adjust our rig, which, like I said, actually was all by Shannon Davis. He was the primary investigator for this bit of work. And he adjusted the rig and then reran it through using the parameters that they were actually advertising. And we did that on different scale systems and a whole bunch of different areas to try to determine how they came across.

Dave Bittner: And what did you find?

Ryan Kovar: Yeah. We found that, you know, ransomware from LockBit said that LockBit 2.0 was the fastest, LockBit 1.0 was the second fastest. And then third place was Cuba ransomware. So when we ran the same bit of work, we found slightly different. We found that LockBit 1.0 was the fastest. Second place was a ransomware family called PwndLocker. Third place was LockBit 2.0. And then last place, just like LockBit, was a ransomware family called Avos. So we found LockBit 1 and 2 were Top 3, but maybe not the one, two, three orientation that they had called out.

Dave Bittner: Do you have any insights as to what is going on under the hood in terms of, you know, why would one family be faster than another? Are they rolling their own encryption here? Are they using, you know, preexisting libraries? What - any thoughts there?

Ryan Kovar: You nail on one of the most interesting things that we found. So we went in with a lot of hypotheses that either all the ransomware families would have similar encryption speeds or that they would be, frankly, completely different. And we started seeing that they were kind of grouped, to be frank. And for LockBit - at least LockBit 2.0 and LockBit 1.0 and even PwndLocker, they have a similar encryption method in that they only encrypt the first portion of the file. So LockBit 2.0 only encrypts the first 4 kilobytes of a file and remains - you know, leaves the remainder untouched. What's interesting about this is if you're dealing with a plain text file that's a terabyte and you only lose the first 4 kilobytes of it, that might be perfectly fine. And, heck, with Windows Word, you know, that might be just the header.

Dave Bittner: Right.

Ryan Kovar: But for a database file or a bitcoin, if you lose the first 4K of that file, you've lost every single bit of that file. And so their method of only encrypting a little bit, especially when you start scaling that to terabytes of data, is actually a very smart idea because you ruin enough of it where you still need to pay for the decryption. Other encryption families encrypt the entire file. And they may use stronger encryption. Or they might use weaker encryption. But they're encrypting the whole file. We also found that - you know, we had some ideas that memory or disk speed might impact the encryption speed, which - disk speed would have an impact, but it wasn't the most significant. The largest was actually the CPU. So the faster the processor, the faster an encryption, which then makes quite a bit of sense because, obviously, doing encryption is completely math. And that's what a processor does on the system. So...

Dave Bittner: Right.

Ryan Kovar: We would see some variance there, which is also why we tested every bit of these ransomware on the same system with the same operating system, with the same memory, with the same hard drive speeds and everything like that.

Dave Bittner: You know, as I was reading through your research and what you mentioned, you know, of only encrypting the first 4K of a file, for example, it made me wonder, could that be of use to - to a victim's advantage in their recovery process? If you know that you've been hit by an organization that only encrypts the first, you know, 4K of a file, could you - could that speed up your recovery process, because now you only have to pull the first 4K of the encrypted files and, you know, graph them together? I'm sure I'm oversimplifying it here. But is there anything to that line of thinking in your estimation?

Ryan Kovar: It's an interesting area to go down. The problem that we had was in order to get a decryption key for these ransomware is you actually have to pay the ransomware families. So that's a step that we weren't willing to go into for our research. So we're not - we haven't done a lot of work on the decryption, sadly, just because that would actually involve putting money back into the ransomware ecosystem for their next nefarious purpose.

Dave Bittner: Well, and that actually leads me to my next question, which is, is there any importance on the decryption side? I mean, we've certainly heard anecdotal stories about how different strains are faster or slower in the decryption side or even more or less successful in the decryption side. If I'm investing my money in trying to get my files unlocked, you know, it seems to me like that would be something where there would be a competitive advantage as well.

Ryan Kovar: Yes, absolutely. I often say that the choice to decrypt is kind of like your choice of whiskey. It's a very personal decision. I've had a lot of questions from people asking, like, should I decrypt? Should I not decrypt? Should I pay the ransom? Should I just restore from backups? And that's not something I can really give a lot of guidance on. What I can say is it would appear to us, based off our preliminary testing, that financially these ransomware families are not geared towards making money from the people who are being victimized but rather the people who are doing the victimizing, the actual people who are buying their service as - ransomware as a service.

Ryan Kovar: So I would say if we go back to Adam Smith, the economics are that they're very concerned with making sure their primary customer, as a ransomware as a service, who are the actual criminals who are sending off the spearphishing emails with the ransomware links - they're more concerned in the speed and quality of encryption rather than the speed and quality of decryption. So that is kind of my belief on this area - that the - from a financially motivated development point of view, these families are trying to make their customers happy. And in this case, their customers, the ransomware as a service gains, are the people who are buying the ransomware service to actually, you know, attack another organization. So the best part of this ransomware is definitely the encryption. And, you know, anecdotally, it does not feel that the decryption is quite to the same level of sophistication.

Dave Bittner: Right. So we're looking at the big picture here. You know, based on the information that you all have gathered, what are your takeaways? What are the recommendations to the defenders out there?

Ryan Kovar: The recommendations that I have - and this kind of goes back to our original research - is you don't have time to stop ransomware once it starts. And frankly, you know, I put out some numbers there of, you know, three, 4 1/2 minutes to four hours. I would really challenge any SOC in the world that can effectively respond to a global ransomware endemic of, you know, even a three-hour ransomware. And so what our work was primarily when we first started and then also as we've continue down this research is to give data back to network defenders of - if you have to spend your cybersecurity dollars, if you have to spend your cybersecurity time, where do you prioritize? And probably the place that we would recommend is trying to stop ransomware from starting. And so really move left of that boom, the boom in this case being the actual ransomware infection, and try to find and detect ransomware before it gets on your system.

Ryan Kovar: The interesting thing about that in our research and after talking to a lot of ransomware defenders and consultants is that ransomware binary itself, the actual thing that we call ransomware, is actually the very last thing that most ransomware groups put on a system. Anecdotally, one person we talked to said they were seeing that the time from the ransomware binary entering the network to actually being executed was only two minutes or three minutes but that the adversary had been on the network for 4 1/2 days. And what's nice is if you think of it like that, you quickly realize that the life cycle of a ransomware adversary is almost the same as a nation-state adversary or an APT adversary, which many of us have been working and defending against for many years.

Ryan Kovar: So if you change your perspective and stop thinking of ransomware as something that's so terrifying but rather the final aspect of a chained life cycle advanced attack, you can really start looking at this in a different angle and adjust your defenses better and duplicate effort in places. Or rather, you don't have to duplicate your efforts because you're already looking for spearphishing emails. You're already looking for lateral movement. You're already looking for persistence. You're already looking for exfiltration of data. And these are all things that happen in a ransomware attack. They're all these things that happen in a nation-state attack. So as long as you're looking for both, you'll be able to find ransomware before you have to deal with the encryption schemes.

Dave Bittner: Our thanks to Ryan Kovar from Splunk for joining us. The research is titled "Truth in Malvertising?" We'll have a link in the show notes.

Dave Bittner: The CyberWire podcast is proudly produced in Maryland out of the startup studios of DataTribe, where they're co-building the next generation of cybersecurity teams and technologies. Our amazing CyberWire team is Rachel Gelfand, Liz Irvin, Elliott Peltzman, Tre Hester, Brandon Karpf, Eliana White, Puru Prakash, Justin Sabie, Tim Nodar, Joe Carrigan, Carole Theriault, Ben Yelin, Nick Veliky, Gina Johnson, Bennett Moe, Chris Russell, John Petrik, Jennifer Eiben, Rick Howard, Peter Kilpe, and I'm Dave Bittner. Thanks for listening. We'll see you back here next week.