Google Drive used for malware?

Dave Bittner: Hello everyone, and welcome to the CyberWire's "Research Saturday." I'm Dave Bittner, and this is our weekly conversation with researchers and analysts, tracking down the threats and vulnerabilities, solving some of the hard problems of protecting ourselves in a rapidly evolving cyberspace. Thanks for joining us.

Jen Miller-Osborn: We were actually following up and along with some other activity that this group - we call them Cloaked Ursa. They're also known as APT29, Nobelium or Cozy Bear, depending on which nomenclature you're more familiar with.

Dave Bittner: That's Jen Miller-Osborn. She's deputy director of threat intelligence with Palo Alto Networks' Unit 42. The research we're discussing today is titled, "Russian APT29 Hackers Use Online Storage Services, Dropbox and Google Drive."

Jen Miller-Osborn: They're one of the more dangerous APT groups that are out there. They have long been considered to be affiliated with the Russian government. And they are responsible for some very long-range impact attacks such as SolarWinds - has been attributed to them. And even before that, the hack of the United States Democratic National Committee in 2016 was also attributed to this group. So it's one that we pay a lot of attention to. And this use and abuse of different cloud and social media hosting services 0 we've been seeing them use quite a bit, especially in the last year or two, in an effort to try to use the reputations of those services to get past potential blocks on where their malware could be hosted or pulled down from because as a general rule, a lot of these services are - they're just - they're blanket-trusted if it's coming from there, and everyone uses it for so many things. And it requires a secondary component for really scanning kind of what the different potential packages could be.

Jen Miller-Osborn: But we found this follow on with Dropbox as we've been following them because they had been very active this past year. They're actually still active. There's been some recent activity attributed to them even since we were talking about it. It was more of a natural evolution kind of, as we were following them to see them abusing yet another cloud service. And we wanted to make sure that as - when some other organizations discovered them abusing other services, that that was highlighted because it is something they're using to try to take advantage of those trusted reputations.

Dave Bittner: Yeah. And I suppose just to make it crystal clear here, I mean, it's - is it that it's difficult for an organization to block, you know, Google Drive or Dropbox or, you know, Microsoft Azure - any of these big cloud services because they are so broad and so vast, and indeed, folks rely on them for a lot of the business they do day to day?

Jen Miller-Osborn: Exactly. And that's why we're seeing these attack campaigns, especially some that are more technical, where they can, you know, encrypt their payloads or make them look more legitimate. So that makes it a challenge even for those services to find this malware. And it's - yeah, to your point, it's impossible to have, as an organization, even as a person. Just trying to operate, I think, on the internet in this day and age, you have to access Google Drive and Dropbox and Azure. That's just kind of - I don't want to say the cost of doing business but just the reality of, you know, this increasingly interconnected world.

Dave Bittner: Well, let's go through what you all were tracking here together. Can you walk us through the campaigns?

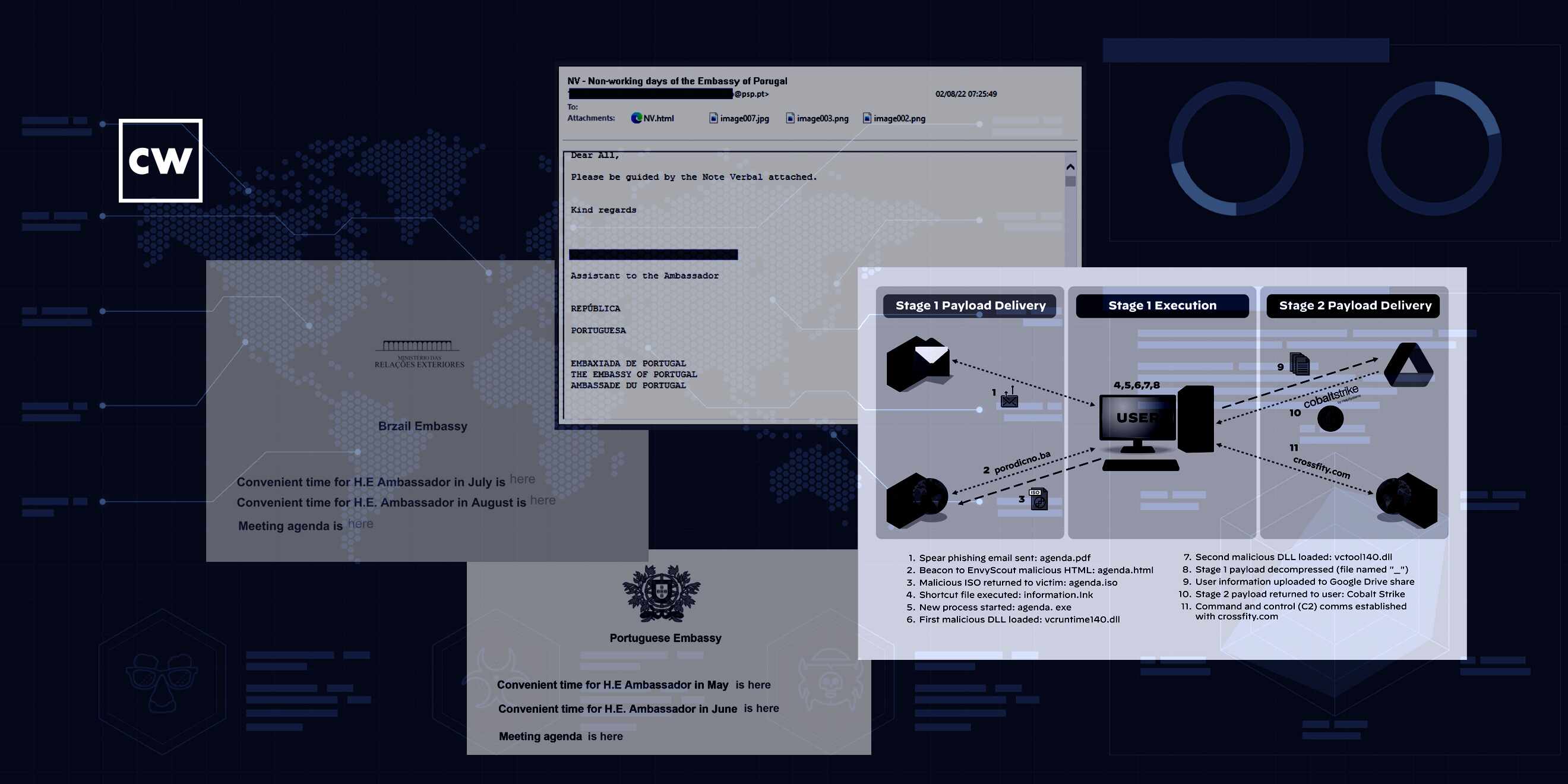

Jen Miller-Osborn: Sure. So we've been tracking a couple of campaigns, as well as some other organizations. And when we started pivoting around, looking for some similar ones, that's where we stumbled upon what we found. A few weeks after another organization reported on them abusing Dropbox, we identified them doing another campaign. This time, this was targeting a NATO country in Europe, and they were using what appears to be a legitimate invitation that they found for an upcoming meeting with an ambassador in Portugal. Interestingly, we saw them send the same attachment twice, which isn't something that we see necessarily. The one only real key that this was honestly not legitimate, obviously, was there was a typo in the email for how it would've been addressed for the actual common parlance.

Jen Miller-Osborn: But we saw them still abusing and continuing to abuse Dropbox. And they're also being attentive to the malware that they're using that's being served. For the one - the case that we observed, in particular, the malware that was served to the victim was last modified only about two hours before the actual spear-phishing message was sent to the target. So you can see they're paying close attention and doing some level of customization and also making it difficult to detect these. You know, they're not letting their malware just sit out there for people to find or researchers to potentially poke at. They're being very judicious about when it's actually available for a victim to pull down.

Dave Bittner: Yeah, I mean, talk about, you know, spear-phishing, indeed. That's highly targeted, it seems.

Jen Miller-Osborn: Yes. And they are known for being very highly targeted. This is kind of their bread and butter, in particular with diplomatic missions. They have been targeting diplomatic missions since at least 2008. So they've had a lot of time to work on their social engineering.

Dave Bittner: So let's dig into some of the details here. I mean, let's say, you know, I'm someone who they're targeting here, and I'm going about my day minding my own business. And I get this email that that seems to come from the Portuguese Embassy. And that's something that I think I'm interested in. What happens next?

Jen Miller-Osborn: So if you opened the email with the weaponized attachment, it would install itself on your system. And then it would start to begin looking for the second stage to pull down, which would be calling out to a Dropbox or a similar kind of cloud-hosting provider. So there's that level, still, of removal where the first-stage malware is on a system, so now to get the second stage, there has to be a successful interaction with the C2 server before that will then be pulled down. And we see that quite a bit. We're increasingly seeing that across all attackers, but we definitely see that a lot with more espionage-motivated attackers, where they try to be careful that it's not a researcher like me that they've accidentally compromised or has somehow gotten in the way so I can get more of their custom malware. They've checked to make sure that it's the victim that they wanted before serving it, you know, because the harder it is for researchers to get ahold of custom malware, the more difficult it is for us to signature it. And with some of the really advanced groups we see, especially for their second- or third-stage malware, they're very, very careful about when they serve that out because they want it to last as long as possible.

Dave Bittner: So if I get that second stage sent to me, do I need to interact with it to get it to run, or is it all happening automatically behind the scenes?

Jen Miller-Osborn: Oh, it's all automatic at that point. Once you open the email, they are off to the races without any help from you.

Dave Bittner: And what are they after here?

Jen Miller-Osborn: In this case, it looks like typical long-term compromise for, you know, sensitive diplomatic missions and potentially negotiations that are going on, which is a target that we have seen them go after consistently over the years. The interesting things that we have seen is it looks like we saw a bit of a shift towards some Western diplomatic missions between May and June, but when you look at the geopolitics between May and June, that also would make sense from a prioritization and a targeting perspective where you'd expect to see an actor that is serving the Russian government targeting areas and diplomatic missions where there's a lot of, you know, tension or potential activity going on during those time frames.

Dave Bittner: One of the campaigns that you all outline here seems to be going after folks in a foreign embassy in Brazil. It caught my eye that I guess on the main page of this email, they misspelled Brazil. That would strike me as a red flag to Brazilian citizens, but perhaps I'm getting ahead of myself.

Jen Miller-Osborn: Nope. Little things like that, yeah, we just continue. And that points to that there are humans involved in this, right? Sometimes, they make mistakes, or there'll be a little typo. It was the same with the other one where it was one little thing. And that was a key to us that, oh, that doesn't look quite right, and same - if it's coming from your embassy, and they're misspelling your country? Or it's coming from any embassy, and they're misspelling their own country? Yeah, I think that would be something worth checking into, maybe, before you clicked on everything.

Dave Bittner: Yeah. I mean, it's sort of a fascinating contrast, isn't it? Because on the one hand, we can see how deliberate and careful and targeted they are, and yet something like this slips by.

Jen Miller-Osborn: Yep. And sometimes that's because there's different people responsible for it. You know, the people that are carrying out the technical access components are not necessarily the people who are crafting and sending the spear-phishing messages. So there can be a gap in ability there.

Dave Bittner: One of the things you highlight is a tool called EnvyScout. What exactly is going on with that?

Jen Miller-Osborn: EnvyScout is essentially a dropper for additional malicious files that they might want to install on a network, and it can be customized to install or beacon out to install whatever the attackers want. So it's very - it's a very lightweight, very small piece of malware, and it's a great way for the attackers to be able to customize and potentially change out what the actual malware is that they deliver to the network. In this case, we also saw them using the perennial favorite of all hackers, it seems, these days, which was Cobalt Strike. And that's definitely something that's making it more difficult for defenders because we see everyone from, you know, ransomware actors all the way through these sophisticated nation-state attackers like Cloaked Ursa all using that same tool, Cobalt Strike. And that - from a defense perspective, until we can get additional malware, another second stage, another third stage where it's more customized to a group, this could be anyone. And it makes it very difficult for defenders to prioritize how they're going to respond to it because getting Cobalt Strike beacons from your network is becoming increasingly common.

Dave Bittner: Right.

Jen Miller-Osborn: And you don't have any way of telling unless you have the additional malware, who is this? Is this Cloaked Ursa, where I need to pay attention immediately because if they have Cobalt Strike on one of my machines, they could - within the next 10, 20 minutes, they could own an entire, like, domain server? Or is this a coin miner, where yes, I want to get to it, but I don't need to call people in over the weekend to do it?

Dave Bittner: Yeah, that's fascinating. Are there any other technical aspects of this report that you think are worth pointing out or drawing attention to that people should know about?

Jen Miller-Osborn: In particular, Cobalt Strike that, for those that are still struggling with defenses against that, it is just - it's critical. It's not something that organizations can kind of look at as something to be down the road. There's too many different attackers all exploiting it for it to not be prioritized at this point because much as the current environment is very similar to, it's not really an if. It's a when you're going to be compromised. When it comes to seeing Cobalt Strike in your environment, it's not really an if. It's a when you're going to see Cobalt Strike. And hopefully it will be for something that isn't incredibly serious. It won't be a group like Cloaked Ursa. But it could be. And that's going to be a very bad day for any of those organizations.

Dave Bittner: You know, usually, we talk about protections and mitigations - and we'll do that - but it strikes me that when you're dealing with an organization that is this targeted, that is this specific in their targets, does that even apply? What are the odds that, you know, someone at any random organization is going to find themselves in a group like this's crosshairs?

Jen Miller-Osborn: It depends on the organization. If you fit their kind of targeting and profile, then if you haven't already. Hopefully that's accurate (laughter).

Dave Bittner: Yeah.

Jen Miller-Osborn: And if you have, then you've already recognized how very sophisticated some of these groups are such as this and how very quickly they can move around an environment. And you recognize that it's something you need to be protected against. This is - this group is another reason we really talk a lot about the zero trust concept. As that term comes around again, becoming increasingly critical, because you have groups like this who are incredibly technical, who will take advantage of supply chain and your trusted relationships, who will take advantage of legitimate cloud-hosting services and social media platforms and who can get away with it successfully because they are very technically skilled. And you need to recognize that from the defense standpoint and be able to react accordingly. And in some cases, it can be as simple as, do you need access to all of these different applications in your corporate environment? With a lot of the cloud services, you can argue no. But, you know, for some of the social camp, the social media ones where it's - like, we saw them abusing Trello - or, you know, historically LinkedIn and Facebook have also been abused. That's something that people need access to at work. You know, some of those are things that you can kind of shut down, at least potentially, from a work network. But then you also have to recognize there's others you can't, like Dropbox. And how are you going to make an effective business protection decision knowing that you have to allow that access into your environment?

Dave Bittner: Yeah. It also seems to me that, you know, cloud services like Dropbox or Google Drive or - they're practically the poster children for Shadow IT because, you know, if you get in the way of someone trying to do their job and they feel as though they need to access Dropbox, they're going to find a way.

Jen Miller-Osborn: Exactly. And that then becomes its own problem of people doing it, that you aren't aware of it. And that just opens up all sorts of issues for a company for a potential sensitivity. That's one of many reasons I have been recommending lately people try to do attack surface management scans or have a plan to get an organization - a company that can do that kind of service for you to give you an idea of what an organization's - your actual organizational footprint looks like online. You know, what ports are potentially open? What isn't passed? What things like that do we discover that are tied to your organization that aren't officially tied to your organization? Or, you know, that dial-up modem that someone used 15 years ago that no one ever turned off that's tied to a printer that's still, you know, connected into the production network - little things like that. And those are the same things that attackers are looking for when they're looking at an organization.

Jen Miller-Osborn: And people need to increasingly move to viewing themselves from that same global viewpoint of, what do I look like as a potential victim? What do I look like as a target from someone who can only view what they can find on the internet about me? And then use that to make informed decisions. Every time I've been involved, organizations have invariably found a nontrivial number of devices that they didn't realize were still operational or were still connected to their network because, you know, device and network management is a challenge. And the older and larger an organization you are, the more of a challenge that is.

Dave Bittner: Any other recommendations here in terms of protecting yourself or mitigating this sort of thing?

Jen Miller-Osborn: The only thing I would add - and it's not necessarily related to this. It's related to some of the things that we've seen recently in the press - is smishing and two-factor authentication are becoming increasingly critical as we see attackers working to defeat them - and not sophisticated threat attackers, like, teenagers looking to defeat them. So organizations need to have an effective policy. A, they need to have multifactor authentication in place, period. And then they might need to look at some other policies for how they handle if someone is spammed with requests to constantly try to authenticate. Does that trigger a behavioral rollover? Or, you know, maybe it temporary locks out an account. Maybe it flags it. Things like that to address what we're already seeing with attackers trying to get around some of the mitigations that we've put in place.

Dave Bittner: Our thanks to Jen Miller-Osborn from Palo Alto Networks for joining us. The research is titled "Russian APT29 Hackers Use Online Storage Services, Dropbox and Google Drive." We'll have a link in the show notes. The CyberWire podcast is proudly produced in Maryland out of the startup studios of DataTribe, where they're co-building the next generation of cybersecurity teams and technologies. Our amazing CyberWire team is Rachel Gelfand, Liz Irvin, Elliott Peltzman, Tre Hester, Brandon Karpf, Eliana White, Puru Prakash, Justin Sabie, Tim Nodar, Joe Carrigan, Carole Theriault, Ben Yelin, Nick Veliky, Gina Johnson, Bennett Moe, Chris Russell, John Petrik, Jennifer Eiben, Rick Howard, Peter Kilpe, and I'm Dave Bittner. Thanks for listening. We'll see you back here next week.