Phishing campaign takes the energy out of Chinese nuclear industry.

Dave Bittner: Hello, everyone. And welcome to the CyberWire's research Saturday. I'm Dave Bittner and this is our weekly conversation with researchers and analysts tracking down the threats and vulnerabilities, solving some of the hard problems of protecting ourselves in a rapidly evolving cyberspace. Thanks for joining us.

Ryan Robinson: Instead of targeting an embassy, in this case it was communication pretending to be from an embassy, and then that's kind of how we got down the rabbit hole to where we are now.

Dave Bittner: That's Ryan Robinson. He's a security researcher at Intezer. The research we're discussing today is titled "Phishing Campaign Targets Chinese Nuclear Energy Industry."

Dave Bittner: Well, let's go through it together here. Exactly what's going on with this campaign?

Ryan Robinson: From a high level this campaign is the Bitter APT are targeting organizations in China which is normal, but what's slightly different about this one is that we actually have the emails that were sent. You know, to the victims. So we have, you know, essentially the social engineering lures. And also who the potential victims are. Yeah. This allowed us to sort of analyze the social engineering tactics that were used and obviously the payloads and stuff. What this campaign tried to do was Bitter APT pretended to be an attache from the embassy of Kyrgyzstan. It invited the recipients to join some sort of conference or round table relating to their field or topic, and then along with an attachment that starts the malware chain of infection.

Dave Bittner: And you mentioned this is -- seems to align with the Bitter APT. What do we know about them?

Ryan Robinson: So as we say on the blog, they're a South Asian hack group and commonly they target energy sort of government sectors, particularly Chinese government departments and scientific research institutions, but they've also been known to target Pakistan, Bangladesh, and Saudi Arabia, quite a few countries. To be more specific than South Asian, other organizations, not us, have attributed them to be from India, where kind of like the base clay of this comes from is that a couple of years ago Kaspersky researchers had noticed that in some code that was created by Bitter APT they noticed an exploit that was -- it essentially came from an exploit broker from a Texas based company called Exodus Intelligence. And then Forbes went in and done an investigation in this and started speaking to a few people. From that, they found out that essentially someone from either an Indian government personnel or a contractor, you know, was able to take this code and somehow that made its way -- and that made its way into Bitter APT code. Bitter APT is much better documented in Chinese sources than I would say in kind of western English based sources.

Dave Bittner: Interesting. Let's dig into the actual phishing lures here. How are they coming at these people?

Ryan Robinson: Okay. So we can divide it up in to a few topics. So we can first talk about who they were specifically targeting and then go into who they chose then personally and what kind of lures they were doing. So when it comes to who they were choosing to target, it was mainly after specific people and institutions. And so the email that we show in the blog, it targets multiple people inside what is a consortium of Chinese nuclear institutions mainly for sort of research and development and then to get this into applied nuclear technology. But what I think they specifically really wanted to target for was the Institute of Nuclear Safety Technology. And there's a big overlap between this sort of semi government institute and academia as well. So what you'll notice in some of the emails is that some of the people that they target are in both institutions. It's kind of like they will target both the institutions a bit more broadly, but then also specific people inside them of which some of those people are in both so they are. So I can't quite tell whether, you know, like the chicken or the egg, they chose the people, then the institutions first, or the institutions, then the people. But what I would say about some of the people is that they're quite prestigious. You know, their own kind of Wikipedia pages now, and they'd be probably well known in their respective fields internationally, not just in China. When it came to how they tried to, you know, bring them on board, kind of social engineer them, lure them and stuff the merger basically emerged around invitations to conferences and kind of round tables. That sort of thing. So the basic structure of the lure would be you got an email. It comes to your inbox. It pretends to be from one of the embassy in China, but more specifically the embassy of Kyrgyzstan. In the bottom of the email it then it sort of throws in a few terms. Okay. You're invited to this conference and, you know, it's along with the embassy and other kind of think tanks and stuff like, oh, the China Institute of International Studies and then and we want to talk about maybe nuclear doctrine or the International Atomic Energy Agency, the IAEA. I'll also point out that some of the people targeted have either worked in the IAEA or they've worked kind of with them. So it would be quite a familiar sort of topic for them. And from that kind of social engineering lure it says, "Hey, like check out the invite." Or the attachment. And that there's an invitation in there. And, you know, that's the start of the malware chain. But when it comes to other lurers we saw is that some builders can have additional decoys then. So when you do download and open, some of them kind of have nothing inside them, but then other sort of more updated lures they put kind of a decoy so you're not just kind of with nothing and confused. So yeah. They'll put sort of more kind of details when you open that up. One thing I'll also kind of say is that when the emails are singed off they're kind of in an open ended fashion. So it kind of leaves it that if you want to reply to them, you can't. You know maybe in that case they get one of their specific targets maybe replying them like, "Hey, I wasn't able to not tell and stuff." They're able to further engage with them, maybe send them a few more things and all, but then what's also interesting and kind of the last part of this social engineering lure type of thing is that they also impersonate specific people. Like I said, they're pretending to be the embassy in Kyrgyzstan. So they've signed off the email about them with the name of an actual attache in the embassy, but I want to point out they're not using this person's email or anything. The email is being created anew. And so what I found is that it's very easy to find this information online. You know, if you go to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs website to Kyrgyzstan you can find the names of these attaches and what their jobs are. Even for Linked In you can find their profiles. So what I think the group have been doing is that, you know, I wouldn't really call this sophisticated, but it's very, very for those so, you know, they've managed to choose who they want to target, who they want to pretend to be in sending these, and they'll even get all that through open source information just by using search engines, Google, Linked In, what have you.

Dave Bittner: Let's talk about the actual payloads and how they're delivered. How are they choosing to go about that?

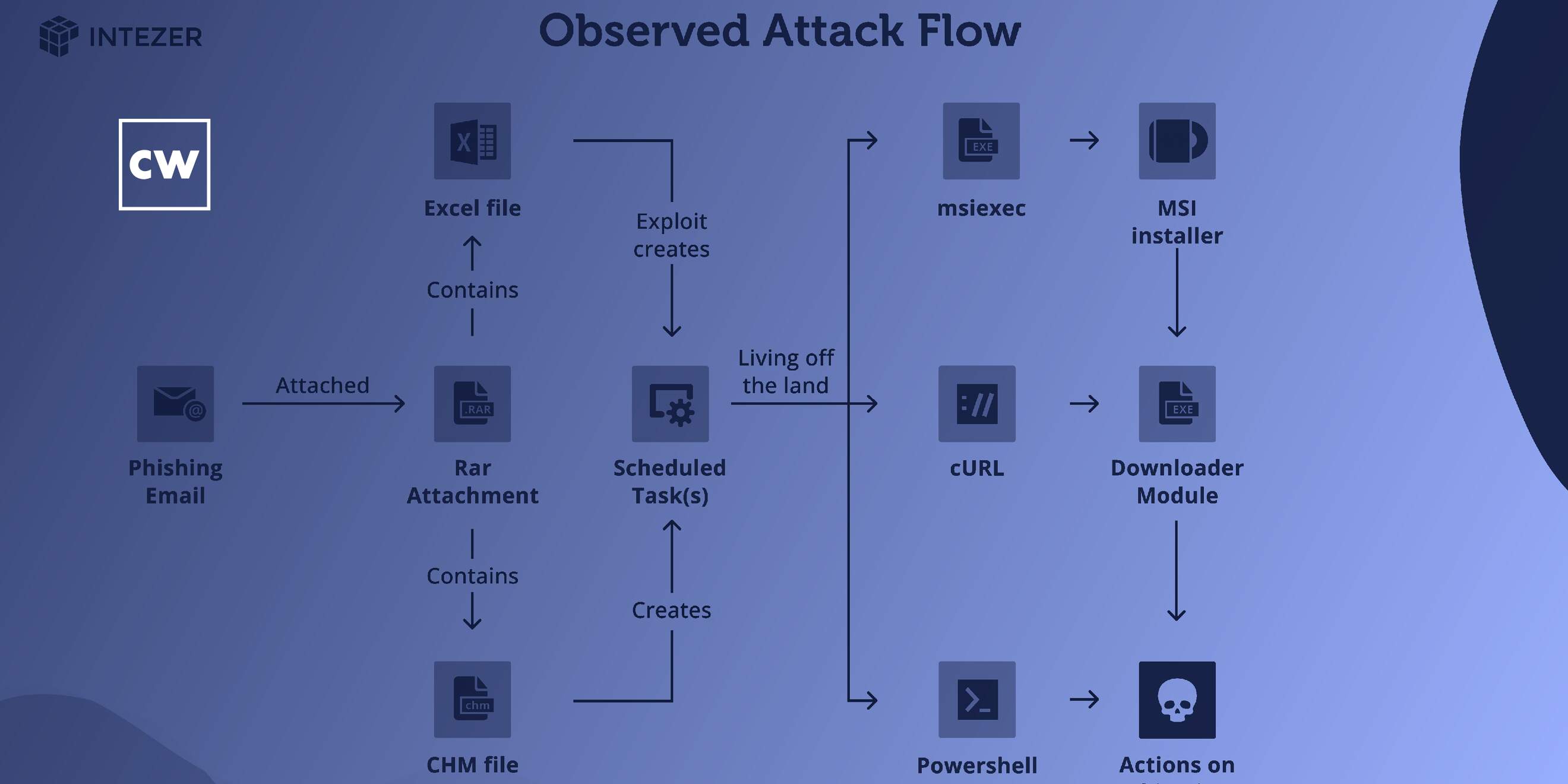

Ryan Robinson: So as I sort of said before, they're an attachment within the body of the email, and first of all they're in a RAR attachment and a RAR is -- it's kind of like a zip file. So just a way of compressing the payload. And, you know, what's nice about a RAR file is that since it compresses the payload it for some static based kind of malware defenses it's not able to analyze that without taking extra steps, i.e with taking the attachment and then decompressing and then grabbing the payload there and then continuing. And so inside that RAR attachment there are a couple of routes which you could take. There is either an Excel file, and that Excel file has what is quite a common exploit inside it, and then that exploit creates a scheduled task which can start the next stage. If they go in to overwrite instead of an Excel file what they'll really commonly use is what's called a Microsoft compiled HTML help file or a CHM file. It's kind of something that's not really used that much anymore like kind of legitimately, but it's something that you might remember if you were using kind of Windows back in the day of like XP or like Windows -- Windows kind of 95 or 98 or something. It's when you click on the help button it sometimes kind of brought up what kind of looks like a web page, but it's not a proper web browser. Those types of files you can still execute code on them, and again that creates the scheduled task. So those scheduled tasks, they're either going to do one of a few things depending on what sort of right the payload has got. Very commonly it uses MSI exact to basically download a remote MSI file and then execute that. And that one's -- and that one's very, very common. That's kind of been documented over blogs and like techniques that they've been using for years. In other cases it uses Carol, so quite a common sort of like command line based sort of HTTP client. So you can essentially make kind of basic web requests and then do what you want with the downloaded data. Or in the later versions we said there's something kind of new. We notice that they've moved over to using PowerShell instead after that, and then once the scheduled task that used these kind of living off the land techniques download, that's where you'll get a kind of downloader sort of module. And then from there extra payloads are sent over depending on what like the task kind of needs. They're known to use like sort of a vast kind of tool set. After that it really depends.

Dave Bittner: How do you recommend that folks best protect themselves against this?

Ryan Robinson: As I maybe said before, that it's not what I would call sophisticated, but they were quite for, so they were, so I would honestly recommend this like a basic level is that, you know, if you're an employee inside a company, energy company, and you have essentially any org, it's that you should probably have a good standard of security awareness around phishing emails. And the reason why I say for this is that the lures themselves can be quite convincing. Like I said, they're referencing organizations that are highly related to the people or, you know, that they've even worked with them before or that they'll be familiar working with. And then they sign off in them like real people. So if you were to say look for the name of that person you'd go, "Oh, yeah. That person's real. That's fine." But it's not from that person. So just because the email says something doesn't mean it's true. Therefore security awareness is good. And when it comes to after that, protecting your computer -- so say, you know, your first stage of awareness fails after that I'd probably recommend just a good sort of EDR/XDR kind of endpoint security, you know, for your computer so if the first stage fails and then you go on to click on one of those files you're going to want to hope that the next levels of security are going to then capture that for you, you know. So if one of like the scheduled tasks is created there are security products that realize that maybe that's not a normal scheduled task. It's pretending to be something else. It can masquerade. It might detect that and block it. So basically I would say awareness first of all, and then, you know, don't get hit. But if you do get hit, make sure you have extra levels kind of of defense and depth strategy.

Dave Bittner: Your blog post mentions that Bitter APT have been around for a while now, for a few years. What's your senses in terms of their sophistication?

Ryan Robinson: You know, in this case the activity that we've seen here isn't particularly sophisticated. You know, it's not hard to understand what's going on and what the chains are. And honestly in this case maybe they don't have to be since it's the first stage. You know, they -- you know, they only have to be lucky once, you know, whereas if you're being targeted you have to be lucky each time. So I don't think maybe they care too much about getting caught in that regards, but where they have been more sophisticated is that in other attacks we've seen like kernel level -- kernel levels as zero day exploits being used. You know, that would suggest quite a bit of sophistication. You know being is up. But, like I said before, it's that they haven't managed to develop these exploits themselves. They've managed to get them off a broker that sells exploits. So while sometimes the skills they themselves might not be too sophisticated, they can still get their hands on essentially a sophisticated tool kit on, you know -- because essentially that's just a money problem. That's all it is. Yeah. I would say they aren't being that sophisticated, but I wouldn't underestimate them. You know, they can -- they can pivot something that hasn't been seen before just because they can buy it.

Dave Bittner: Our thanks to Ryan Robinson from Intezer for joining us. The research is titled "Phishing Campaign Targets Chinese Nuclear Energy Industry." We'll have a link in the show notes.

Dave Bittner: The CyberWire research Saturday podcast is a production of N2K Networks, proudly produced in Maryland out of the startup studios of Data Tribe where they're co-building the next generation of cybersecurity teams and technologies. This episode was produced by Liz Irvin and Senior Producer Jennifer Eiben. Our mixer is Elliott Peltzman. Our Executive Editor is Peter Kilpe. And I'm Dave Bittner. Thanks for listening.