Digital Innovation and the Next Frontier of Intelligence - with Jennifer Ewbank

Andrew Hammond: Welcome to "SpyCast," the official podcast of the International Spy Museum. I'm your host, Dr. Andrew Hammond, the museum's historian and curator. Every week, we explore some aspect of the past, present or future of intelligence and espionage, a genuine 365-degree view of arguably the world's most misunderstood topic. This week, if you leave a review on Apple Podcast or on some other platform, then send us an email with a screenshot of your review to spycast@spymuseum.org, we'll read out some of the best ones in upcoming shows. These can be accompanied by your real name and where you're from or, alternatively, use a code name and a cover story. Coming up next on "SpyCast"...

Jennifer Ewbank: Some of our biggest risks were the risk of inaction. The risk of not moving in a space where our adversaries are moving aggressively was an unacceptable risk to the agency.

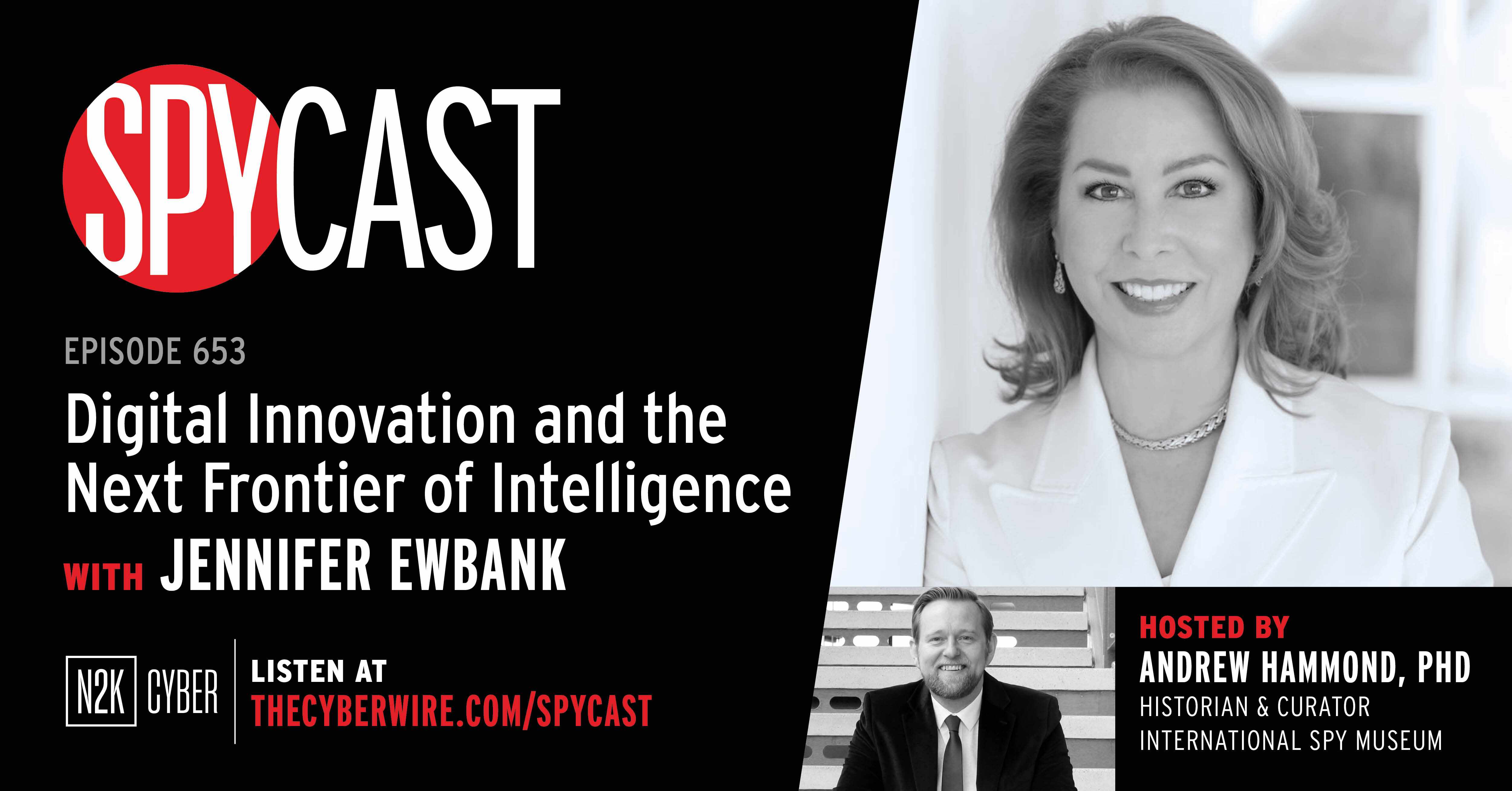

Andrew Hammond: This week, I was joined by Jennifer Ewbank, former deputy director of the CIA for Digital Innovation. Her retirement in early 2024 marked the end of an over three-decades-long career in American intelligence, a journey that took her around the world and to the top of Central Intelligence Agency leadership. Now she has turned her focus to helping best position the United States on the global stage within the private sector. Jennifer joined me to reflect upon her career in intelligence, share lessons in leadership and discuss the integration of technology and the latest innovations within CIA operations and analysis. She was a pleasure to have on the show and she's a loyal "Spycast" listener herself. Very humbling. In this week's episode, we discuss the qualities and skills of great digital leadership; risk management and intelligence; the roles, responsibilities and emotional toll of the CIA chief of station; and how the CIA utilizes the latest in technology and innovation. The original podcast on intelligence since 2006, we are "Spycast." Now sit back, relax and enjoy the show. Well, thanks for joining me. I'm really looking forward to speaking to you.

Jennifer Ewbank: Same here. Thanks for the invitation.

Andrew Hammond: Just to begin with, tell us a little bit more about yourself, who you are and what you've done most recently, which is one of the main reasons why we're speaking just now.

Jennifer Ewbank: Oh, well, thank you so much, Andrew. And thank you again for the invitation to join you today on the podcast. I'm a loyal listener so it's kind of fun for me to now be here. So, my most recent role at the CIA was as deputy director for Digital Innovation. And that is a role where I led one of the five directorates that comprise the CIA, the directorates are Directorates of Operations, many of your re - listeners will know this, Directorate of Operations, Directorate of Analysis, Directorate of Support, Directorate of Science and Technology, but many will not have heard of the Directorate of Digital Innovation, which was formed in 2015 as part of CIA's most let's say dramatic and radical reorganization ever. It was a directorate created in recognition of how digital tech was changing everything about how we live and work outside the intelligence community. And we kind of woke up and realized we better get to work to start bringing in these new capabilities within the intelligence community as well. But your question was broader. And I've been in the national security community for, oh, three and a half decades. And much of that was working in intelligence operations overseas for tours, as we call it, for tours as chief of station and where I led, you know, teams, small, medium and large eventually, in the collection of intelligence and in building partnerships with foreign allies and partners around the world. So, in a way, I guess you could say I came to this role, that I've just recently left, the deputy director of Digital Innovation, in let's say a circuitous path, a non-traditional path, coming from operations to digital tech. But it's been a - it was a great experience, loved every moment of it. And a little disclaimer, I may slip into present tense during our discussions quite accidentally as I've just retired from the agency a couple months ago.

Andrew Hammond: And, so, just for our listeners, just - you know, we don't need to get too into the institutional structure of the CIA, but you've got the director, the directory - the deputy director, sorry, and then underneath them, you have the five directors of the five directorates. Is that correct?

Jennifer Ewbank: Yes. We have different naming conventions. So, the director, the deputy director and then we have five deputy directors for, fill in the blank, the focus, so often called directors as well. So, directors of their directorates.

Andrew Hammond: So, just to put it in context, you were effectively one of the top people at the CIA.

Jennifer Ewbank: Oh, yes, yes -

Andrew Hammond: Yeah.

Jennifer Ewbank: Absolutely.

Andrew Hammond: Yeah.

Jennifer Ewbank: So, yes. And, so, at that top senior leadership level, leading kind of large organization with a globally deployed workforce and partnering with the other deputy directors to kind of deal with all of the big strategic challenges and questions and decisions that have to be made for the agency as a whole.

Andrew Hammond: And help me understand what your priorities were. So, you get tapped for this job, you come in, it's a very dynamic field. Like how does one approach that? So, obviously, you've had leadership positions before as the chief of station and so forth, but what do you do, do you get out a yellow legal pad and start putting down, "Here's the five things I want to achieve in the near term and five things in the longer term," or like how does one approach this type of thing?

Jennifer Ewbank: Yeah. There are lots of different ways. Right? And, so, you know, I came to the role with a sincere, oh, let's say curiosity, an open mind, desire to learn and some humility in that because, you know, I show up as the leader in this digital technology workforce and I don't come with that deep background. I think the first time we met, Andrew, I mentioned that my last coding class, we didn't even call it coding back then, it was programming, but my last coding class was Fortran. Many people wouldn't know what that is. But if you've got like an old industrial control system you need worked on maybe I'm your person, I don't know. But it involved punch cards and then delivering punch cards to a computer center and then, overnight, my compiled program would be delivered on a dot matrix printer printout. And, so, that was obviously not going to be very helpful in 2019 driving digital technology. So, I did come with a real sense of humility. And, in fact, within a week or so of arriving, a directorate had its big annual event and unlike any other part of the CIA or the intelligence community, we had a day-long we called it the DDI Experience in lieu of a traditional government let's say all-hands meeting, where you would come and people would throw up PowerPoint slides and talk about strategy and do a year in review. Instead, it was very much like a tech conference. So, it was visually stimulating, it had great music and we had great tech demos and let's say lightning talk style things. And then I was there as the new leader and said, "Okay, well, now address the workforce." It was a great opportunity. But - and, in thinking about what to say, I just came right out and said it, "You're probably wondering why the heck I'm here," right, "and wondering like what am I going to bring." And, so, just, you know, address that straight up. And then back to the curiosity piece. There was a very intense period of kind of introductory meetings with teams. It's a huge place, it's a huge workforce. We've got, you know, thousands of people, it's all around the world and it covers - and maybe I should just recap that for folks, it's enterprise IT's, global security communications, cybersecurity, data, data policy, strategy, artificial intelligence, machine learning, open-source intelligence, cyber collection, cyber analysis, all the, you know, engineering efforts that underpin these things, plus a training and education role for the entire agency for digital tech. And, so, that's a lot to digest. Right? So, it was a lot of briefings. And I quickly did change the way that we approached all of that because I was not going to be, you know, the technical program manager in that role leading such a large workforce. And, in efforts to provide thorough briefings, I would get, you know, 59 PowerPoint slides and, you know, somebody wants a two-hour meeting to go into a deep dive. And, okay, that's okay sometimes. But what I quickly came to realize is that - and this is where I saw an opportunity to kind of frame how the work would be done, is to really step back and think about two big things. And that was, one, you know, the big why. Like, "Why are we doing this?" Because we're down in the weeds on some tech program that's really important, but it's not really connected to the why. So, why are we doing this, what are our adversaries doing, where - you know, where do we need to be and what do we need to develop to solve problems today, what do our colleagues in the field need right now. And, so, the big why was a piece of it. And then a vision. Like what is it on the horizon - what's our aim point on the horizon, what are we trying to be and how do we get there. And, so, I tried to shift the focus of those discussions at that senior most level to really, you know, emphasize the why and the vision and then, you know, how do you get there. And I think those were two aspects of kind of the change that I sought to bring to the directorate arriving as a let's say operational leader into a technology workforce. That plus, as I've mentioned already, a sense of urgency and a desire to solve problems quickly.

Andrew Hammond: And for people out there that are leading teams at whatever level, I'm just wondering how you approach that as well. So, you came into this job, a very big job, involves a lot of moving parts, a lot of dynamic things going on in the sector. So, like when you come into a position like that, on the one hand, you want to listen to the people that have been there, you want to have some kind of sense of humility, you want to, you know, brief me, get me up to speed, help me get a feel for things. But then, on the other hand, you also don't want to be - you know, you don't want to come across like, "I don't really know what I'm doing, please tell me what I'm meant to know." And then there's also the, "Well, I want to get some quick victories on the boards to inspire confidence in the team that, you know, things are moving in the right direction" versus "I'm going to, you know, not make any major decisions just now until I've got a thorough layout of the field. So, for people that are out there that are leading teams of any size, like how did you approach that kind of tradeoff between listening and action?

Jennifer Ewbank: No, it's a really insightful question because, particularly in a space that's moving so rapidly, right, it's a really dynamic part of the intelligence mission, it is in a constant state of flux. You, frankly, don't have the luxury to wait around until you have perfect information about everything. And, you know, if you do that, you know, if you're standing still at any moment, then you're falling behind because your adversaries are moving really rapidly. So, you have to be able to make decisions and move even while you're refining a strategy and refining your long-term vision. And I found that it really wasn't that difficult for me to straddle that line between humility and a genuine desire to understand and appreciate the important work of the officers who worked for me and to having a vision of where we need to head. I didn't pretend - my vision wasn't let's say I wasn't going to sit down and draw the OV-1 architecture for the CIA's information technology ecosystem for the year, you know, 2030. I was not going to do that. But I had a vision for what that needed to be. It needed to be simplified, it needed to be defensible, it needed to be agile, we needed it to be around the - like I knew what those things were. And, so, it was, in fact, a pretty natural partnership. And one thing that I hadn't mentioned, so, coming to this role, and perhaps it's one of the reasons I was selected, a bit through serendipity along the way, I had the opportunity to lead DDI teams around the world in several locations where I was chief of station. So, leading teams, learning about their work, appreciating them as people and as professionals, but not actually trying to tell them how they're going to build a network or how they're going to conduct a cyber collection operation or how they're going to write their analysis. There's a nice balance in there. And, so, in essence, what I try to do is take that humble personal approach, but with a clear vision for the future and elevate to the larger enterprise level. Is it how everyone would do the job? Probably not. But then, you know, we're all different people and, you know, I'd long since learned that the best thing you can do when you're a leader at that level is to be authentic, really require authenticity to build trust, that if you don't have trust, you don't have anything. So, for me, it worked.

Andrew Hammond: And I'm just wondering if part of the reason why you felt so comfortable doing that was I guess if you're an operations officer or just even working in intelligence more generally, you never have a completely saturated information environment, you always have to proceed on the basis of an imperfect information environment so, therefore, that's kind of second nature. I'm just wondering if you think that fed into it in any way.

Jennifer Ewbank: I think that fed into it a great deal, in fact. And, so, you know, leading whatever team at whatever level at whatever location around the world for the CIA, there are two things that are constants no matter what you're doing. And one is just if you - as you've said, Andrew, is you have to be able to make decisions with imperfect information. Intelligence, it isn't about knowing exactly what's going to happen. I mean, you have those moments, but that's not it. It's about, you know, delivering a decision advantage to our policymakers. Decision advantage doesn't mean that I can tell you precisely what's going to happen and when. You never have perfect information. And, so, you have to be able to move still, you can't be paralyzed by a desire to seek that last detail when, particularly in a digital tech space, like the world is moving rapidly all around you. So, yes, in operations, but I think it extends beyond, it extends to the analytic work, it extends to, you know, support and technology, you have to be able to move with imperfect information. And then, the second piece, and it's really just the flip side of the same coin, which is fundamentally the CIA's work is all about risk at some level, it's about understanding risk, it's about accepting the risk, it's about mitigating the risk, but moving nevertheless. And, so, those two things together, I think when you apply them to the digital tech space, are really relevant. And one thing that I should probably add to this, because it doesn't come up very frequently in literature that I've seen and podcasts, videos of things that I've watched or conferences I've attended, there - of course, there are all sorts of ideas on what is good leadership. Right? We can probably, you know, quote all sorts of fantastic literature about what makes a good leader. All that stuff is probably true. I would add that there are a few things that are necessary for digital leadership. And I have to say, when I came in in 2019, it used to drive me, you know, bananas every time somebody would throw the word "digital" in front of something else because I just thought, you know, "Okay, you're just making stuff up." But, in fact, digital leadership turns out to require a few different kinds of skills in order to be successful. And that was, you know, the ability to think creatively, to not be stuck in some sort of a - let's say the rut that people have created ahead of you, the ability to take risks, to embrace failure as a natural, okay, say, stepping stone towards some big success in the future, the - an inclination - let's say a predisposition to seek integration of capabilities because you have to be able to work across tech silos and you have to be able to work with mission partners in operations and analysis and elsewhere, you have to be able to communicate, you have to have trust, you have to understand what they need. All these things have to come together in a way that's not quite traditional leadership. So, integration and failure and innovation and creativity, all that is really, really necessary in the digital tech space. And it does require some unique skills. And, interestingly, when I reflect on life in intelligence operations, those things really are emphasized in operations. It's about integration, it's about operational creativity, it's about urgency, it's about accepting failure along the way, because you will fail. It's a lot of those things. And I think they had direct relevance to leading in the digital tech space. [ SOUNDBITE OF DIGITAL BEEPING AND TYPING ]

Andrew Hammond: So, you mentioned risk and the inherent nature of risk in the intelligence enterprise. So, here's a question for you as well. So, with risk either as an operations officer or being the director for Digital Innovation, how do you calibrate your approach to risk in those situations because, so, yesterday here at the Spy Museum, the staff had a briefing on our pensions and, you know, the closer you get to eventual retirement, the more money you want out of international stocks and the more you want in bonds, for example. So, bonds, like you could see, for example, CIA leadership saying, "We want someone to come in to be the director of Digital Innovation who's going to be a safe pair of hands. We don't need recklessness, we don't need to lose stuff." But then you could all - but then you also - to just keep your money in bonds, it means that you're not accumulating. So, you could also have an approach where it's like, "Let's get somebody in who's going to take gambles, who's going to really make us surge ahead." But then there's, you know, there's cost to that as well if it doesn't go right. So, how do you - I don't know, either as a case officer or when you were in this role, like what was your approach to risk? Like what would your portfolio be like, if you want to put it like that? Would it be, "I'm going to go for volatile international emerging markets," or "I'm going to stick with bonds" or "I'm going to have a diversified portfolio"? Sorry to put this in pension terms, but -

Jennifer Ewbank: No, it's an interesting framing, Andrew. And, so, it is a different type of risk, but they're - you know, they're common threads. So, if I look back on my life in the operational world, there were moments when it was literally - the risk was somebody's life. And, so, you felt that deeply. And I still feel that today to - with all the people I - all the amazing people I worked with over the years are foreign spies and being responsible for their well-being, potentially their life, that really crystallizes your views about risk and taking every measure you can to mitigate that risk to protect the person that you have sworn to protect. So, that's one kind of risk. Coming to the technology world, it was interesting translating decades of that operational risk management into a very different environment. And, so, I quickly came to recognize, or at least quickly came to articulate and advocate that some of our biggest risks were the risk of inaction and that the risk of not moving in a space where our adversaries are moving aggressively was an unacceptable risk to the agency and to our intelligence mission, which includes our spies around the world and our analysts and our technologists and our support officers and you name it. And, so, here we are trying to do this really critical work and building, in essence, the future of intelligence and every day doing that against the backdrop of very capable, aggressive adversaries. And I'll just name one. Our most capable and our most aggressive adversary in the digital landscape today is the People's Republic of China with, you know, the greatest level of resources, the most sophisticated capabilities, with the strongest support for government, with the most ambitious plans. You know, all of it aligns to represent tremendous, tremendous challenge for the U.S. government. And, so, you know, if I came in one day and said that I wanted to - you know, this translates into programs and people and money and all that at the big enterprise level. Right? And I said, "Well, I'm going to continue spending. Let's take a hundred million dollars a year for some legacy capability that delivered something that was really useful in 1995." What I used to point out to people was that was an active decision to not build the thing you need for the future that's going to win this competition with our adversaries. And, so, you're going to need a better reason than momentum or at least just, you know, kind of maintaining. And, so, I looked at risk I think a little differently than some people in the technology workforce did. They looked at risk, not everybody, but in terms of contract execution, delivering capability that was secure, all those things are, you know, very, very important, but we needed to be secure and deliver things rapidly and we needed to be able to churn and create the next new thing if we wanted to buy down what was the big risk of losing this competition with our most capable adversaries.

Andrew Hammond: And, so, would there be a sense that, you know, the Directorate of Operations and Analysis have been - you know, operations and analysis have been around for quite some time. So, let - you know, let's just think about this as the case officers, the operations officers are the infantry, they're out there they're doing what they've always been doing. And then we have the analyst that's like the artillery, you know, they are sort of a bit more distant, but, you know, it's very important that they do what they do effectively. So, would - is there - was there a sort of sense that the Directorate of Digital Innovation was the - like the invention of the tank, like this is the new place where the battle is being fought, this is the new technology that we have to master? It's not a perfect analogy, but I'm just trying to get a sense of is some of the - a lot of the competition and the action, the other things are a bit more stable because they've just had more time to be settled, but this is a new like the Wild West, this is like kind of a new pla - a new battle ground, a new place where things are being fought over. So, this is actually where a lot of the action is beginning to move as oppo - you know, it's always going to stay in the other places, but it's increasingly moving to this place?

Jennifer Ewbank: It's two things at the same time. So, as you've described, yes, it was the new thing. It's no longer the new thing, but it is the thing. Right? You think about cyberspace and everything that's happening there and everything that's happening with research and development in digital tech. So, artificial intelligence, think about quantum computing, think about, you know, AGI, the future, all this stuff is happening today. And, so, it is the place where, you know, we are competing, we are going toe to toe with our adversaries every single day. So, that is true. At the same time, however, in order to do the operational mission, in order to do your analytic mission well, it actually is an integrated mission now. You can't - it's not something separate from digital tech. You have to have those capabilities and those people sitting side by side in order to succeed in what, you know, one might characterize as one of the more traditional lines of business. So, you know, today, it is more difficult than ever to be a case officer, an operations officer working, you know, in some capital around the world trying to collect secrets about the plans and intentions of our adversaries. And, so, it is super challenging in this world of ubiquitous sensing and big data analytics and all sorts of other things that are working against you every single day. And, so, you have to have every advantage when you hit the street. And that means partnering with, frankly, a lot of people from the Directorate of Digital Innovation, you know, it's data science, it's cyber collection, it's open source. Open source is a huge piece of the CIA's mission now. You have to have all of that stuff to give you every possible advantage. And it's impossible to think of it as separate. It has to integrated. You know, there was a time when, for decades, at the agency where - and I - you know I lived and worked that where I was a case officer, an operations officer, went out to do my thing and occasionally, you know, somebody would come and sprinkle technology over the top of my activity. And that is not the way it can work anymore. It has to be deeply integrated. And that same goes for our analytic work, same goes for - frankly, for business operations, just the business of running a large complex agency. You know, the efficiencies, the automation, lots of stuff that has to happen. It's no longer separate from, it is, you know, integrated with.

Andrew Hammond: You mentioned being a station chief in different places. So, I'm just wondering can you tell our listeners how that works. Does it work like - so, in the State Department, you get some people that become a regional - they're known for being the - a regional kind of ambassador, they could be an ambassador in three different Arabian countries, for example. And then you've got other people that maybe they do Germany, they do the UK, they do Russia, they are known as they're a safe pair of hands and they're sent to different places and there's less geographic coherence, there could be other skillsets that people have. So, like how does that shake out for the CIA? Do you tend to get a regional focus or is it completely random or does it depend on your level of competency? I know it's probably a combination of all of them, but maybe you could just help the listeners understand, you know - I know you can't name the places, but just help them understand a little bit more about how that shakes out.

Jennifer Ewbank: It's a good question. And, so, you know, we tend to grow up in the organization aligned to usually a geographic region, sometimes a functional region - a functional subject. So, our Mission Centers are regional or functional. And, so, officers grow up for a while in that environment. So, naturally, you will tend to gravitate there as you get to a more senior level and you're ready to become a field leader let's say, a deputy chief of station or chief of station at a small place as your first time. So, my first chief of station role was, in fact, in the geographic region where I had spent my time recently. And, so, that does happen. A lot of things come into play. Do you have subject matter expertise on the country, the region, the issues that they face? Sometimes it's the issues less so than the geography because the issues kind of transcend, you know, where a country is. If you are an expert in counterproliferation, then maybe you'd be in lots of different places around the world where that mission is most relevant. If your expertise is in counterterrorism, frankly, that applied almost everywhere. And still does today. So, do you have the subject matter expertise? If you have the language capability, that was always a plus, you know, a leg up. But we are very good about training officers in language. We have I think the best language training program in all of government, at least that I know of, to prepare our officers to be able to do really complex work in a foreign language. It's also competitive. Right? So, it's going to depend on how well you have done your work to date and the reputation you have as a leader. So, it's not a matter of, you know, completing certain prerequisites and then, voila, you'll be a chief of station. It's completing certain prerequisites in order to be considered at the table. And then it is a competition. And, so, any number of officers are going to apply for the jobs. And, as you might imagine, some are going to be a lot more popular and interesting than others. So, it's - it was the case decades ago where people tended to stay in a geographic region for a long time. So, let's say I was an Arabist, it was the case decades ago where I would stay in the Arab-speaking world. I think that's less so today. There's a lot more kind of flow across geography and across subject matter. We encourage people to have broader ranges of experience. Certainly, post-9/11, the terrorism fight drove a lot of that, too, because it didn't matter where you served, you were expected to serve the terrorism mission, too, as we all, you know, wanted to and needed to. So, I think that also contributed to the broadening of the backgrounds for officers going into chief of station roles. But if I reflect on the places where I have been chief of station, they were places where I have geographic expertise and, with the agency's support, good language skills.

Andrew Hammond: Okay. And final question before we flip back to digital transformation. So, I'm just - when you were talking earlier about the foreign spies that you have worked with, that you've recruited and run and so forth, it made me think of this book that I came across years ago called "Sleeping with Ghosts." And it's by a war photographer called Don McCullin. And he used to keep all of the negatives that he shot in boxes under his bed. And he said that, you know, it was almost like he was sleeping with ghosts because all of these negatives followed him around. So, I guess it just made me think is there - you know, this is something I've never heard discussed anywhere. Is there some part of a case officer psyche where you keep these people and, you know, you clearly can't, you know, talk about them and write op-eds about them and so forth, but, you know, it may be you, there may be a very small number of other people that know about them, is there some part of a case officer that carries around all - you know, all of the spies I've recruited, what happened to them, where are they now? You know, I know that I can't probably go online and start like doing open-source Intelligence on them, I can't compromise them in that way. But you're - there must always be part of you that's wondering what are they doing now, are they okay. You know, there's ethical parts involved. So, I'm just wondering, is there some kind of sleeping with ghosts/sleeping with spies kind of analogy that could be made? Is that something that case officers discussed? The - maybe not the names, but maybe just the general sensibility.

Jennifer Ewbank: I love that question. And you're right, I haven't heard that discussed much. I jotted down the name of the book here because now I'm going to go read it. But, absolutely. Right? It's interesting because you carry those people with you for a lifetime and the commitments that we make to our sources, spies in common parlance, those are commitments for a lifetime. It's a commitment to do everything we can to protect them as they've agreed to do something very important and potentially highly risky in order to help the United States. You never forget that. And, so, it is true, you think about them from time to time for a lifetime. You wonder, "How is he doing?" You know, "Where is he? Has he retired from, you know, his secret career? Did he retire and leave without being compromised? Is he happy? Does he have a family?" All these things. And the second part of that is that no officer will ever, I don't know, lose - get over the sense of heartache they feel when a spy is captured and executed. And there have been a number of those over the years, as you would know as a historian. And what's lost in that story is the personal relationship, the personal piece. There are officers who feel it deeply who will never lose that feeling. They feel it deep in their heart just the heartbreak of that tragedy. And, so, that feeling is what propels officers, particularly those who've experienced that horrific tragedy, somebody else in their orbit. Right? If they've experienced that, as you can imagine, their commitment to the mission, commitment to compartmentation, a commitment to security, their commitment to everything, which was already at a - conducted at a very high level, is only intensified. And, you're right, you could never go online and Google someone's name because, of course, that has potential to compromise that person. And they're - you're always left wondering. I will share one quick vignette. I had the unique opportunity in my career to go back many, many, many, many years later and see a source that I had worked with, you know, intimately, closely for a number of years early in my career. And had the opportunity to go back and meet him at one point. And it's - the intensity of that is - was really striking on both sides, on his side, on my side. It was like seeing a close family member again after many, many, many years. And, you know, just being able to recount, you know, everything that happened in our lives and, you know, our families and the rest of it, it was - it's intensely personal, something deeply, deeply felt. So, I guess that's a really long way of saying I suppose we do sleep with ghosts for the rest of our lives. Yeah.

Andrew Hammond: And that's something that you think about, you can remember your first, your last, your favorite, the most difficult one, the -

Jennifer Ewbank: I think I remember them all. [ SOUNDBITE OF DIGITAL BEEPING AND TYPING ]

Andrew Hammond: Let's pivot back to digital transformation. So, I think it would be interesting here to - you know, if we try to go through each component of what you were overseeing and trying to drive, it would probably be, you know, redundant. So, I think it could be interesting to focus on one or two examples. Maybe we could look at AI or something like that. Like tell us what's going on. So, we spoke about it maybe at a higher level, but, tangibly, like what would that involve? Like what would you do? Like help us understand what you would do with your job.

Jennifer Ewbank: Oh, yeah, goodness. Well, it's like leading any large organization, there's going to be a lot of, you know, people and resources being on your calendar most days. And one of the wonderful things about the role was that I oversaw officers who themselves were very senior enterprise leaders for the agency. So, the chief information officer, the chief information security officer, the chief data officer, et cetera, and their counterparts leading other parts of our mission who themselves had authorities and responsibilities for the agency as a whole. So, it was a really unique dynamic. But I'll maybe pull the thread on a couple things. One, let's say open-source world. And, so, you know, the open-source world's been really fascinating. And it's the subject of a lot of discussion these days, certainly with industry, certainly with academia and, you know, just interested people out there track such things. And it's a great example of successful digital transformation because open-source intelligence in the intelligence community today, and the CIA is the leader there, it's really all about advanced digital capabilities today. So, years ago, it - we had, you know, people all around the world who would listen to radio broadcasts and watch television broadcasts and read the newspapers and translate things and then, you know, send that material back to Washington and Washington would compile it and then we would deliver, you know, in essence, kind of open-source newsletters each day to ambassadors and to political officers and others who were serving around the world and embassies and then, of course, to policymakers in Washington. And that worked extraordinarily well. We had unparalleled subject matter expertise. But, again, with this transformation as of 2015, it was a realization that that was never going to scale with the way open-source information was now being - was then being made available in - on digital platforms and digital capabilities. We would just never be able to scale because the volume was going up literally, you know, an exponential curve. You know, so, we could never hire people at an exponential curve to manage that flow of information. And, so, it became the ground for experimentation, for development of new capabilities on rapid timelines and doing so in an environment that was relatively, I would say, more secure. Because it was open source, we had less risk involved, if you will. And that allowed a lot of experimentation and the occasional failure and the ability to move really rapidly. And, so, open source led the way in terms of applying artificial intelligence and machine learning to every step of the process that you could imaging. So, let's say a - finding that open-source material on a digital platform somewhere. So, ingesting that, transporting that, identifying a language, doing machine translation, doing summarization, applying the same sorts of things to radio and TV. So, it's, you know, audio to transcript, transcript to translation, translation to summarization, whatever it might be. You've got all these steps in order to deliver information on a rapid timeline to consumers. And, so, at the very beginning of, I would say, the big large language model explosion, right, so everyone remembers 2022 ChatGPT hit the press and, you know, the most rapid adoption of any new technology in history is any new digital technology, you know, the numbers of people who signed up within the first six months, which is just extraordinary. Right? But we were right there in the mix in the open-source world playing with large language models and generative AI. And, on a very rapid timeline, I think unfathomable in government, developed a capability that was called Osiris and it's been written about publicly that helps analysts and others digest and consume massive amounts of information. I mean, the downside to having so much information available and so much information then presented through automation and AI is that you have so much information presented you can't even possibly consume it. You can't work the same way you worked 20 years ago and come in each morning and read every article about, fill in the blank, your topic because you just could never do it. You couldn't have the capacity. So, there needed to be a new way to consume that information to make sense of it so it's not just a flood. Right? And, so, this capability really did an amazing job of, A, summarizing events, things that are happening with just massive amounts of reporting behind each event and then allowing analysts or others to engage with that information through a chat bot to ask questions, you know, to help refine our thinking, to challenge our thinking. And, so, all of this really fantastic capability that was to our understanding the most advanced use of a large language model anywhere in - certainly in government and potentially in industry at the time, And that's the story of open source these days. It's really that - you know, how do you make sense of it all? And, so, I used to use this phrase quite frequently in speeches and in presentations because everyone talked about data, data, data, data, data, data. Right? Data's the new oil, data's the new this, a colleague had "data's the new bacon." I never really understood that one. But data's fine. You could drown in the data. But data's not information and information's not insight. And, so, the magic was in taking data and creating insight. And, for us, that really required human machine partnering and AI with machine learning. And, so, open source is where, you know, we are really able to play with the new capabilities and move quickly and do some extraordinary stuff on rapid timelines. And, all of that, all of that experience informs and enables the stuff we're then able to do in more secure environments after that.

Andrew Hammond: Wow. And I'm just wondering - in this, let's just stick with the example of open source so we've got one to hang our hats on. With the example of that, would there be like generational differences in how open people were to this type of stuff? Or what you were saying to me earlier was that actually you would be surprised. There's also some people that see that this is necessary for the mission so they actually - they might not be digital natives, but they kind of get it. And help me understand, you know, if there were any, you know, generational dynamics at play here.

Jennifer Ewbank: Absolutely, there were differences there. And, so, on both ends, on the open-source production end and on the user end, so the consumer end. So, within open source, of course, there were those who were quite wedded to the legacy way of doing work. And there - and, trust me, I loved it. I was one of the most avid consumers and I just loved the expertise resident in the amazing people who worked with us all around the world. And, so, I felt lost, in a sense, when that approach changed dramatically and we emphasized technology instead, which helped us scale. Right? We never would have been able to scale. And we never would have succeeded during the pandemic had we not already done this hard work of moving largely to a technology-based capability. But, on the consumer end, it was also the same because, today, we talk about open-source intelligence, so INT, you know, OSINT as the INT first resort. We talk about that a lot. And we used to say that, but I think it was never realized that way. There was still - for decades, there had been a bias toward secret information. Somehow, if it was secret, it was better. Somehow, if it was secret, it was just more relevant. And, so, we never presented intelligence that way. We never said, "Oh, well, here's a secret report, therefore, you should believe it." But it tended to have a lot more weight than the open-source information. And, so, with that dynamic for decades, of course, there was a certain sense that it was a secondary capability. Unfair, completely unfair. But, again, just as I was describing earlier with this dynamic between, say, operations and digital tech or analysis in digital tech where the complexity of the mission is driving that integration, driving organically the partnership that has to happen in order to achieve success, the same thing is happening in open source because, again, think about how hard it is to collect real secrets today. It's really hard. So, what's the natural thing you need to do? You need to maximize the exploitation of open-source information to narrow the range of secrets. You have to go out and collect. And, so, you know, no one wants to do high-risk, high-cost collection, whether it's espionage, human espionage or technical collection, in a secret way if that information is available somewhere openly. And a lot of information that used to be collected clandestinely in the old days is available openly if you know how to find it and if you have the expertise to present it. And, so, again, the mission is driving this organic expansion of the role of OSINT. And that is a wonderful thing because the expertise that is out there in the OSINT communities is really just unparalleled. And I hope others would agree that we have finally achieved the vision of OSINT being the INT of first resort.

Andrew Hammond: Mhm. And how did - you know, because you were still in your position when the war in Ukraine breaks out. How - as much as you're able to tell, you know, lots of stuff has been released in the public domain and so forth. So, as much as you're able to tell us, how did that affect what you were doing or how did that accelerate some of these revolutionary or evolutionary changes or how did that affect the nature of OSINT or emerging technology? You know, a huge open-ended question. Interpret it whatever way you think is the best way.

Jennifer Ewbank: Well, let me frame it one way and then I'll pull the thread on a few of those capabilities. So, in my role as deputy director for Digital Innovation, there was no major challenge, no major issue around the world, to say one of our priorities where DDI was not at the table literally for, you know, every update, for every conversation, for every strategy meeting. And, so, whether it was Russia/Ukraine or Israel /Gaza or what's happening - you know, the tensions in the Taiwan Strait or, you know, the latest terrorist threat or, you know, et cetera, et cetera, et cetera, et cetera, et cetera, whatever is the priority on the calendar is going to get the senior leadership's attention and time because you need to understand how things are evolving and you need to guide the collection and the analysis and the rest of it. So, DDI was a critical partner in all of those discussions. And, specifically looking back on Russia/Ukraine, there was a lot of talk about the role that cyber would play in that conflict. And, certainly, we've seen this in any number of publications I'm sure, but there was an expectation that Russian cyber capabilities would play a larger role that ultimately they did. Now, to be fair, I mean, they did a lot and they continue to do a lot in cyber space to undermine Ukrainian capabilities. They've constantly - the Ukrainians are constantly under attack, one kind or another, in cyberspace. Certainly, Russian collection has posed, you know, a threat as well to military plans and intentions. But I think it's fair to say that analysts and observers expected it to play a slightly larger role than it did. And, in a way, that's also a testament to the success of Ukraine's partnerships with a number of allies. You know, I won't name everyone and maybe go into specifics about what we have and haven't been able to share with them. But those partnerships that helped Ukraine develop really exceptional defensive capabilities and analytic capabilities to understand what's happening. And, so, has digital technology played an important role in Russia/Ukraine? Yes. Has - have, you know, intelligence service - allied intelligence services done their part to help? Yes. Open source is really interesting. And I'm sure you were thinking of this when you asked the question, but - and I'm happy to - I'm always happy to be proven wrong because I'm sure I'm wrong quite regularly. But it may be the first conflict on the world stage that everyone worldwide was able to watch unfold through open source. Right? So, everything from people's cell phone videos to the data collection and analysis that was released publicly, do - you just name it. And it almost didn't matter, if you had a cell phone in connectivity somewhere on Earth, you could see this conflict take place. And that's an extraordinarily different environment. And, so, of course, our open-source enterprise and partners across U.S. government are, you know, mining that and, you know, collecting and synthesizing information, just this flood of information, which is also giving really rich insight to analysts in - on a really rapid timeline that you never were able to do in the past. No conflict in, certainly, my tenure in the intelligence community you could ever do that. It's been an extraordinary capability and it has enriched our collection and analysis in pretty exceptional ways.

Andrew Hammond: And there's so much other things that we could dig into, but we're out of time. So, final

Jennifer Ewbank: Ohh.

Andrew Hammond: Quest - final question. So, Charles de Gaulle used to like to quote the Greek poet Aeschylus who said to wait on - you had - you have to wait until dusk to see how splendid the day has been. So, you have to wait until the darkness comes. So, that just makes me - I bring this up because I'm just wondering you have recently concluded a long career in intelligence and I know you've managed to take a break and take some time off and so forth. So, I'm just wondering is there any kind of like insight or clarity or focus that you have been able to get on your career now that it's concluded? I mean, it's a new chapter in your life and your career, but I just mean your career within like the CIA, for example. Is there anything that you've - that sort of came to you when you were, you know, I don't know, hiking somewhere or just taking a break? Is there any kind of like insight that you've derived?

Jennifer Ewbank: Yeah. It's an interesting question. And I take the quote maybe as an opportunity to reflect on the career, you know, that I had the honor of pursuing. And, you know, I came to the careers through kind of, you know, almost accidental channels. It wasn't something I had planned, you know, and sort of fell into it. And I found something that was really special and great for me. It really tapped into so much of what both my mind and my heart wanted in life. You know, I wanted purpose. I think everyone needs purpose. And to feel that sense of deep purpose is special. And I'm not sure that everyone gets to do that in their life. And, so, I'm grateful to have had that opportunity to feel that what I did and what, you know, my colleagues continue to do every day actually does make a difference, it makes a significant difference. And, of course, you know, there's the whole standard thing that people say, you know, our mistakes are public and no one ever knows about our success. And that's okay. You know, we hire for people who don't require a lot of external validation. I didn't need people for 30 years to tell me, you know, that I was successful or exceptional or - in any way. I had the satisfaction of seeing our success and knowing that I made a difference. And, so, you know, leaving a career that you love and, by any standard, a career that you might call an extreme career, something that is just very high levels of, you know, adrenaline and dopamine, you know, all the stuff in your system, leaving that when you do have it as one of your deepest loves in life is hard for people. It is very hard for people. That separation can be very difficult. And, so, for me, what I focused on, it was just, you know, time for me to try something new. Right? And, so, what I've focused on is just gratitude and appreciation for all the opportunities I've had, for the extraordinary people that I've met, both in the service and all around the world. I mean, you know, I've met people on six continents in this line of work. And just extraordinary opportunities that I never would have had in life. And, so, when I think about my career, it's really just, at this point, with a deep sense of gratitude and humility that I had the opportunity to do something so exceptional and meaningful for me for so long. Not everyone gets that opportunity in life.

Andrew Hammond: Hmm, wow. This has been such an enjoyable conversation. Thanks ever so much for your time, Jennifer. I really appreciated that.

Jennifer Ewbank: Well, Andrew, I really appreciate the opportunity as well. I appreciate the invitation. I really love the work that you do there with the podcast. And I will continue to be a loyal listener. Although I probably will not listen to my episode.

Andrew Hammond: But you must.

Jennifer Ewbank: Thank you again, Andrew.

Andrew Hammond: Yeah. Thanks so much. [ SOUNDBITE OF DIGITAL BEEPING AND TYPING ] Thanks for listening to this episode of "SpyCast." Please follow us on Apple, Spotify or wherever you get your podcast. Coming up on next week's show...

Unidentified Person: Both the House and the Senate Select Committees on Intelligence is that we are the people's eyes and ears on some very potentially controversial activities. That's who we are.

Andrew Hammond: If you go to our page at thecyberwire.com/ podcast/spycast, you can find links to further resources, detailed show notes and full transcripts. I'm your host, Andrew Hammond, and my podcast content partner is Aaron Dietrich. The rest of the team involved in the show is Mike Mincey, Memphis Vaughn III, Emily Coletta, Emily Renz, Afua Anokwa, Ariel Samuel, Elliot Peltzman, Tré Hester and Jen Eiben. This show is brought to you from the home of the world's preeminent collection of intelligence and espionage related artifacts, the International Spy Museum.