What malicious campaign is lurking under the surface?

Dave Bittner: Hello everyone. And welcome to the CyberWire's "Research Saturday." I'm Dave Bittner. And this is our weekly conversation with researchers and analysts tracking down the threats and vulnerabilities, solving some of the hard problems of protecting ourselves in a rapidly evolving cyberspace. Thanks for joining us.

Israel Barak: The research was exposed during an incident response, 2021. And it was super interesting for us because as we did a number of different IR engagements across manufacturing, health care organizations and a couple of other verticals, we noticed similarities in the patterns of behavior.

Dave Bittner: That's Israel Barak. He's chief information security officer at Cybereason. The research we're discussing today is titled "Operation CuckooBees: Cybereason Uncovers Massive Chinese Intellectual Property Theft Operation." Well, let's walk through it together. Can we go through, you know, step by step of exactly who these folks are and the methods that they use to do the things they do?

Israel Barak: So absolutely. The data that we have basically shows that this campaign that we dubbed CuckooBees and we're attributing to a Chinese state-sponsored actor that is called Winnti or APT 41 started at least on 2019 and specifically targeted manufacturers in the United States, in Europe and in Asia - and specifically in the defense and aerospace, energy, biotech and pharma sectors, where the operational goal of the campaign was basically stealing sensitive documents, blueprints, formulas, manufacturing-related proprietary data. Some examples that we've seen during the incident response and the investigations include design and manufacturing information related to specific engine parts and airplane parts. So that was the overarching goal of the operation.

Dave Bittner: Well, can we walk through some of the techniques that they're using to get into systems?

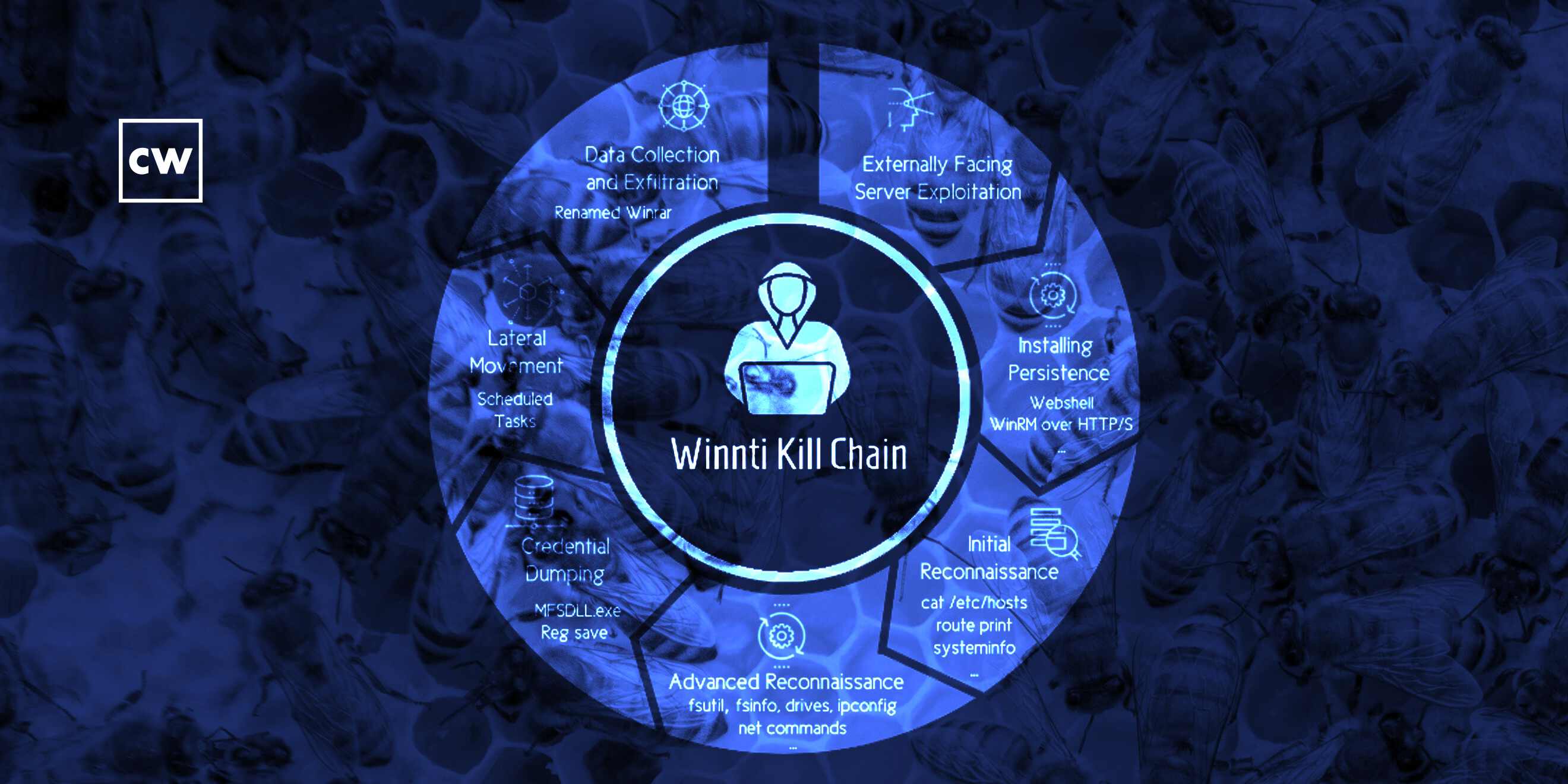

Israel Barak: The first thing that we identified as we sort of untangled the process here is that the initial access that was done into these target networks was typically through the exploitation of vulnerabilities in a popular ERP solution. Some of these vulnerabilities at the time were known vulnerabilities that were just unpatched by the users of the ERP solution. Some of them were unknown or zero-day vulnerabilities at the time. When they were able to compromise that ERP system, they were able to gain that initial access into the ERP system, the next stage was usually to establish some sort of persistence or mechanism that would allow them to kind of keep coming back in and out. The most common technique that we observed was the use of a JSP web shell that they basically embedded in the ERP web application servers. So they created the facade of them communicating from an external network with a legitimate web application, the ERP. But basically, they were able to send commands to those systems that that system then executed for them in the target's environment. That was the way to get back - to get in and out. That was the interesting thing for us. I think it's - you know, we often think about the different ways attackers like Winnti - right? - or APT 41 are able to find that initial access. And sometimes, you know, it's targeting individuals. Sometimes it's targeting the supply chain. And here, I think we see another common example of how an adversary like that, that is a state-sponsored adversary, is developing proprietary zero-day software vulnerabilities that enable them to gain that initial access into organizations where that software is being used.

Dave Bittner: Can you give us a little bit of the background on Winnti themselves? I mean, does this align with what we're used to seeing from them? And what sort of tools do they have in their arsenal?

Israel Barak: It does align with the overarching method of operation that we're used to seeing from Winnti. Winnti is - as a group existed or at least have documented record since at least 2010, and they believed to be operating on behalf of Chinese state interests. And they specialize specifically in cyber espionage and in intellectual property theft. That's sort of - they're known in the industry as sort of the princes of technology secret theft. The techniques that they used in this operation, some of them were known techniques - the use of supply chain attacks, software vulnerabilities, web shells, etc. - for this group. Some of them were lesser-known techniques. So, for example, one of the things that they used to sort of fly under the radar inside the target's network and to stay - or evade detection for a long period of time - this operation continued in some of those target networks for almost three years. And so one of the techniques that they used to sort of fly under the radar and evade detection, which we haven't seen from them before, is a rare abuse of the Windows CLFS, which is a common log file system feature. Basically, it's a feature in Windows that is primarily designed to hold system logging and application logging information. And they use that mechanism to store the payload of the attack - right? - the piece - different pieces of malware that they were using in a way that most security technologies or in an area where most security technologies actually don't really scan or don't really look into.

Dave Bittner: Oh, interesting. So this is a - I don't know, an area where the system keeps some logs. And so by putting their own stuff there, to the scanners it was, nothing to see here.

Israel Barak: Exactly. Exactly. And that was so - that was a - that wasn't - that's a fairly rare technique to see. That's really something that we haven't seen from this particular group in the past. But there was enough - I think there were - there was enough similarity between some of the techniques that they used in operations that they ran in the past for us to be able to attribute that operation to that group with a very fairly high level of confidence.

Dave Bittner: You mention that this group was able to stay within networks for multiple years in some cases. What ultimately led to their discovery in this case?

Israel Barak: And so in some of these engagements that we got called into, some of these incident responses, one of the things that ultimately triggered the suspicion of the organization was the amount of data that was being exfiltrated from the system. And so over the years, this adversary was able to collect from some of these organizations hundreds of gigabytes and sometimes more of intellectual property - design documents, manufacturing procedures, blueprints, etc., etc. And in some cases, it raised the suspicion that something is happening that the organization or the defender was just not aware of. We got called into these engagements and were able to sort of unravel that whole chain of events that led to it.

Dave Bittner: What are your recommendations then? I mean, for organizations to best protect themselves from an ATP group like Winnti, what sort of things should they have in place?

Israel Barak: So it's a great question because on the one hand, the first thing that we recommend, you know, is always - we always all need to get better - right? - in doing the basics - right? - in making sure that we know our networks and we understand what assets we have, what the status of security hygiene is in our networks. And we do what we - you know, the best we can to maintain good security posture and good security hygiene. And it's always, I think, the best practice, regardless of what type of threat or rescue trend mitigate. But at the end of the day, when you're dealing with a threat actor like this, which is a far more sophisticated adversary than what you would typically find in the ecosystem, they always have a way to find initial access into an organization, right? And whether it is compromising an individual that has access to the network, whether it's compromising the supply chain, this is a type of adversary that spends weeks, months, sometimes years trying to get initial access to their targets. Eventually, they make it in despite our best efforts in security posture and security hygiene.

Israel Barak: One of those things that we need to really get better in is proactively hunting for these threats, right? This is this sort of a low and slow operation. And so we need to adopt this proactive threat hunting approach, right? We need to be able to look across the data - all right? - across the data in our enterprises - right? - endpoint data, network data, identity and access and other types of security data, and proactively look for patterns of behaviors - right? - chains of behaviors that may, you know, in and of themselves look legitimate. But when you look at the chain of events over time, they expose a chain of events that is indicative of a malicious activity. And that's something that oftentimes evade real-time detection or prevention mechanisms. But when you adopt a threat hunting mindset and you analyze data and patterns over time, specifically looking at those chains of behaviors, you're able to expose those low and slow operations relatively early in the attack lifecycle and avoid the majority of the impact of them.

Dave Bittner: Is that something that is available to those small- and medium-sized businesses out there, you know, who are dealing with limited budgets? Are there ways that they can use those kinds of approaches?

Israel Barak: There is. I think today there are a number of segments in the market that offer these type of capabilities when you look at detection and response technologies in the EDR space, or the Endpoint Detection and Response space, or in the XDR space, the Extended Detection and Response, I think you're seeing a growing number of technologies and solutions that are focused on automating the vast majority of this proactive rounding process and augmenting it with people that are experts in analyzing that data and understanding what it means from a threat perspective. I think the other resource that is becoming very, very accessible for enterprises of all sizes is an analysis done by the MITRE organization. So on an annual basis, basically the MITRE organization, which is a non-for-profit organization, primarily a DOD contractor, they basically run an annual exercise that is emulating very sophisticated adversaries and is evaluating different approaches and technologies in the market and their ability to detect those minute changes in behaviors and change their behaviors and expose that type of malicious operation in progress. And so all that information is publicly available on the MITRE website that essentially describes what their observations are and what technologies and capabilities can enable enterprises, really of all sizes, to adopt this type of approach.

Dave Bittner: It really is an interesting situation we find ourselves, isn't it? I mean, a group like Winnti, they're not going anywhere. They're well-funded, you know, globally insulated. It's something that we're going to have to deal with for the foreseeable future.

Israel Barak: I agree. You know, one of the things that I think is interesting in this incident that we reported on is - and we briefed the FBI and the DOJ on the investigation. And if you recall, the FBI in their China 2025 report from 2019, they called out the Chinese aggressive state-sponsored intellectual property infringement strategy. And I think one aspect of the CuckooBees incident is that it shows that despite that diplomatic and other efforts - right? - to curb that behavior, exactly as you say - right? - at least as it pertains to our domestic economy, you know, that aggressive intellectual property theft and infringement strategy may have not really changed much. The other thing I think is interesting to note about these type of adversaries is that we need to reframe what a win strategy is; that is, defenders against these adversaries. Because - and I think you hit the nail on the head. This type of adversary will not stop trying to get into a particular target's network just because that target has good security in place, right? The reason is that they have no motive - right? - to stop doing it. That target has something that they want. There's really no price or no risk for them to pay for trying again and again and again. So there's no reason why they wouldn't continue to try it until they make it.

Israel Barak: And the interesting thing - and when when you try to counter the operation, from a defender's point of view, when you try to counter that type of adversary, is that the win strategy is not to make sure that they, you know, they never come back. But the win strategy is to make sure that you increase the time intervals in which they come back. So instead of - after you push them out the first time, usually what you'll see is that they come back after a couple weeks and try again. And you push them out a second time, they'll usually try to come back after a couple weeks. But if you operate the right program and the right strategy, what you'll see is that you can dramatically increase those time intervals. And then instead of coming back, you know, every couple weeks, they'll come back every couple months or every year. The reason is when you get very, very good at exposing what they're doing in your network, you create a price for them to pay. Because when you expose their method of operation - by the way, that's part of the rationale behind us making this information public - when you expose the method of operation, you dramatically increase their price. Because now they need to rebuild things in order to start executing again. And that is expensive, right? It's something that they do. Every threat actor does it. But there's an expensive price to pay for targeting a target that is a sophisticated target that can expose - right? - that operation, that impacts other operations that they have in flight. And so when you run an effective operation for detection response investigation, you're able to create a certain form of deterrence against the threat actor like that that will manifest itself in the increase in the time intervals in which they will come back. They'll make sure to build, be very meticulous in what they build, before they come back and try to target the network.

Dave Bittner: Our thanks to Israel Barak from Cybereason for joining us. The research is titled "Operation CuckooBees: Cybereason Uncovers Massive Chinese Intellectual Property Theft Operation." We'll have a link in the show notes.

Dave Bittner: The CyberWire podcast is proudly produced in Maryland out of the startup studios of DataTribe, where they're co-building the next generation of cybersecurity teams and technologies. Our amazing CyberWire team is Rachel Gelfand, Liz Irvin, Elliott Peltzman, Tre Hester, Brandon Karpf, Eliana White, Puru Prakash, Justin Sabie, Tim Nodar, Joe Carrigan, Carole Theriault, Ben Yelin, Nick Veliky, Gina Johnson, Bennett Moe, Chris Russell, John Petrik, Jennifer Eiben, Rick Howard, Peter Kilpe, and I'm Dave Bittner. Thanks for listening. We'll see you back here next week.