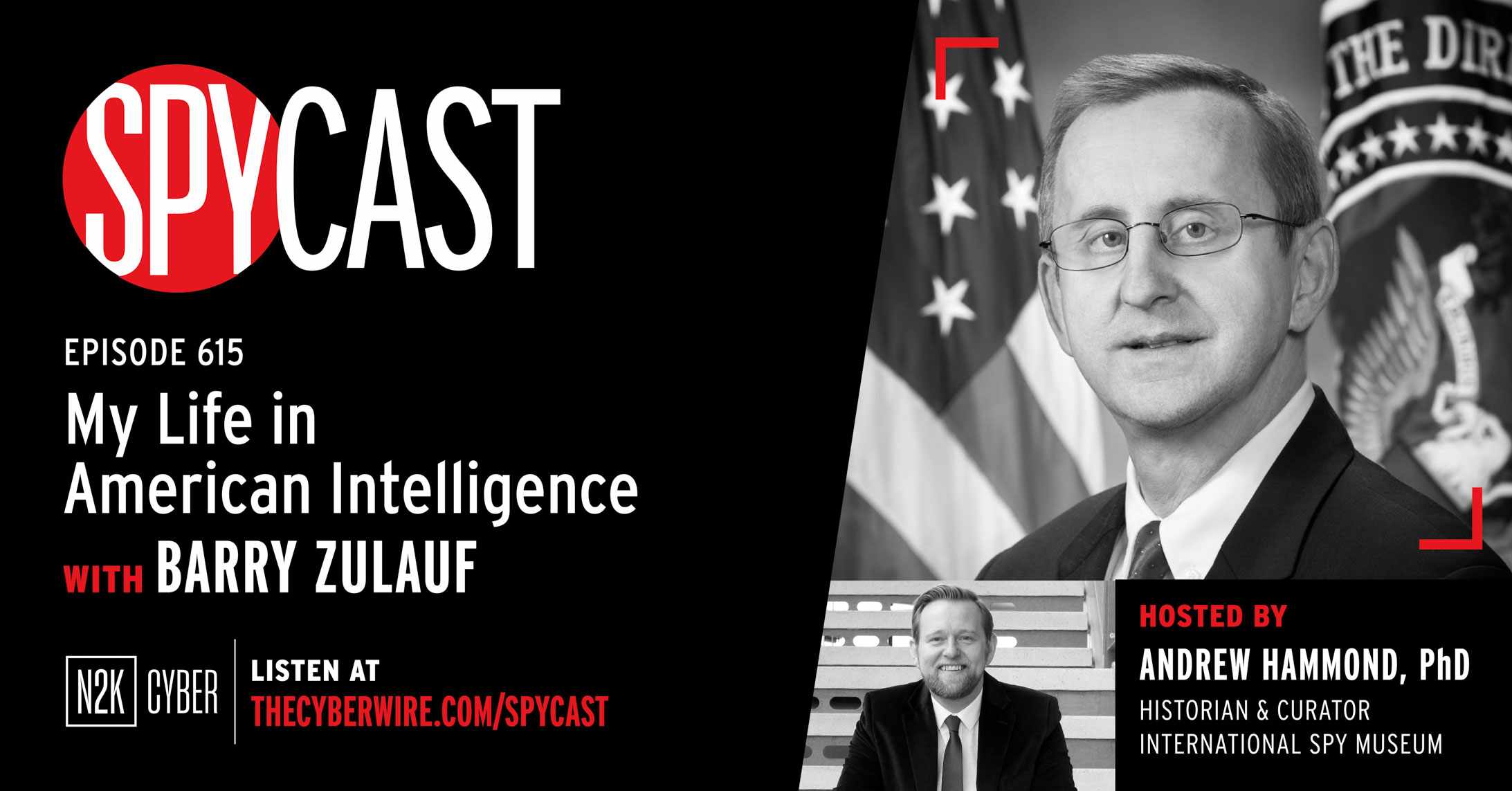

“My Life in American Intelligence” – with Barry Zulauf

Andrew Hammond: Welcome to SpyCast, the official podcast of the International Spy Museum. I'm your host Dr. Andrew Hammond, the museum's historian and curator. Every week, we explore some aspect of the past, present, or future of intelligence and espionage. Please support the show for free by giving us a five-star review on Apple Podcasts. If you could leave a single sentence, it will help other listeners find us. It can literally take less than a minute. Thank you. Coming up next SpyCast: '

Barry Zulauf: I had -- I had to sit down with some management there afterwards, and I was -- I was told, "Well, you're never going to be the Chief because of what you did." [ Music ]

Andrew Hammond: This week's guest is Barry Zulauf, who has worked all over the U.S. intelligence community, from Naval Intelligence to the DEA, and from the National Intelligence University to the Office of the Director of National Intelligence. As he puts it, "I speak cop, Navy, Intelligence, and Defense." He currently works for the Department of Defense as the Defense Intelligence Officer for Counternarcotics Transnational Organized Crime, and Threat Finance. He also has a PhD from the University of Indiana. But if you'd like to find out more about Barry or this episode, go to our web page or the cyberware.com/ podcast/spycast for extended show notes, links to further resources, and a full transcript. In this episode, Barry and I discuss what is the intelligence community? How American intelligence is organized. The establishment of the Office of the Director of National Intelligence, and the intelligence components of the Drug Enforcement Administration, or DEA. The original podcast on intelligence since 2006, we are SpyCast. Now, sit back, relax, and enjoy the show. I'm so pleased to speak to you, Barry. We met last year, and it's always been in the back of my head. I really want to pick your brains about a few things. So thanks for coming into the studio to allow me the opportunity to do so.

Barry Zulauf: I appreciate you bringing me here. As, you know, historian to historian, this this is a great opportunity to talk about all things past. I do need to say before we get started, though, I'm speaking in my personal capacity today as a professor at various places and as the President of IAFE, the International Association for Intelligence Education. I am a senior executive in the intelligence community, but I'm not speaking for the Director of National Intelligence or any organization or the Department of Defense or the Boy Scouts or the Lutheran Church in America or anyone. Just me.

Andrew Hammond: Okay. Okay. That's good to know. I think that you're one of my favorite guests, and we haven't even done the interview because last year you sent out a tweet saying "I've just discovered this superlative podcast called SpyCast."

Barry Zulauf: Oh, yeah.

Andrew Hammond: So I just want to thank you for that, and I can promise I never paid you off or anything.

Barry Zulauf: It's not a paid advertisement here. I'd have to return it if you -- if it was a paid advertisement.

Andrew Hammond: Just before we get going, and know that your role every morning on the Potomac River.

Barry Zulauf: Yep, yep.

Andrew Hammond: Can you tell the listeners just a little bit more about that? One of the things that we try to do on the show is humanize intelligence professionals. So tell us a little bit about more about that, and did you row here this morning?

Barry Zulauf: I did. In fact, this morning at, you know, 5:00 a.m. For local listeners, if you're crossing the Key Bridge between 5:00 and 6:00 a.m., you will see us down there. I'm a Master's Level rower, which doesn't necessarily mean I'm very good. It just means I'm old.

Andrew Hammond: Okay.

Barry Zulauf: And it's a sport that I got into 12 years ago when my knees started to give out because it's sort of a low-impact sport, and it's a great metaphor for working in an intelligence organization because you have to know where you're going in the dark sometimes. And it's if -- what I do is I row in a -- in a crew of eight with a coxswain, and we all have to row exactly the same together for an hour and a half. If anybody makes a mistake, the boat -- the boat slows down. And I believe even though I'm a -- I work in my mind either as a professor or as an intelligence analyst, having a healthy body is important, too. I see so many people in my line of work that are physical wrecks because they spend the entire life in the office eating pizza for -- nothing wrong with that, but you -- you have to. You have to work the pizza off the other way. In corpore sano mens sana.

Andrew Hammond: I know that you've had various jobs in and around the intelligence community over the years. So I want to explore a few of them but I wonder, just to begin with, this idea of the intelligence community, can you just in a couple of sentences, tell our listeners what that is?

Barry Zulauf: Well, the intelligence community has a formal definition in law now. Since the National Security Act of 1947, it specifies specific agencies that have legal authority to carry out espionage, or spying, against other countries or agents of foreign powers, and to analyze that information, keep it secret, where -- usually secret. Sometimes it's not. We can talk about that later, and provide it in an objective and unbiased manner to decision makers. People like the President of the United States or the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff. That these agencies are the only ones that have that authority, and they have money set aside specifically to enable them to do that. They have -- they have special authorities. Some of them are in the Defense Department, most in fact, three-quarters. And these are organizations that maybe you've heard of like NSA, National Security Agency. They do signals intelligence, National Geospatial Intelligence Agency, they do geospatial intelligence, imagery, and some you haven't heard of. For example, there's or organizations inside the Justice Department. We'll talk more about this later, but the one that I was most formative in, which was the Drug Enforcement Administration, has its own intelligence community agency. There are 18 of them now, and they are ranged, some of them in the Defense Department, some of them in State Department, some of them in justice. And they're a community because they all have this mission of pulling together intelligence and supporting decision makers. It's a -- community is kind of a misnomer, because it implies that we all cooperate 100% on everything that we do, and we don't. But we all have departmental responsibilities. I'll do a little history here. There's a there's a similar concept, the Holy Roman Empire of the German nation. There's a historian joke. It's wasn't holy. It usually didn't have Rome as part of it. It wasn't much of an empire; it was more like a confederation, and it was only part of it in Germany. So the intelligence community is similar. It's -- we have common responsibilities, but we have -- we have differences as well.

Andrew Hammond: Good old Voltaire, I think about.

Barry Zulauf: Yes. That's -- yes. Yes, indeed. That was Voltaire's joke. One of his jokes.

Andrew Hammond: So it's, obviously, existed for some time. We've got the CIA in 1947, the FBI which comes out, even further back, 1908.

Barry Zulauf: Yes.

Andrew Hammond: So the community has existed. When did it first be thought of as the IC, the intelligence community? Is it when it was written into law, or was there some other moment of creation that we can point to?

Barry Zulauf: Well, the first actual mention that I can find of the term "intelligence community" exists in something called the Hoover Commission. Former President Herbert Hoover was asked in 1955 to look into the structure and function of the government in the United States, and there was a subcommittee that looked at intelligence organizations. And that was the first place that I can find that the phrase "intelligence community" was used, 1955. It existed without that actual name in law, as you said in 1947, when the CIA was brought into existence, and there were a handful of other organizations. State Department had intelligence. Navy had intelligence and since then, it's much bigger. Eighteen organizations now, and the most recent legislation that specifies all of that was the Intelligence Reform and Terrorism Prevention Act, IRTPA, of 2004, which created the current structure of the intelligence community. It exists in law. I'll just say, you know, the "roots" of the intelligence community -- we'll put that in quotes -- in the United States, go back to President Washington, actually to General Washington, who he, himself, led the intelligence capabilities in the Continental Army: Personally paid spies, gave them orders, consumed the information that they were able to give, and he continued that when he was President of the United States. So there was a very tiny intelligence community then, but it did exist. In English-speaking world, it goes back at least as far as Sir Francis Walsingham, who was Queen Elizabeth I's Intelligence Chief. And from him, we get the responsibility of doing what is very, very distasteful for some intelligence professionals, and that is telling the boss what he or she does not want to hear. His job, as some listeners will know, was he had to convince Queen Elizabeth of something that she didn't want to hear. She did not want to know that her cousin Mary was plotting against her, but he was able to give the intelligence, show that information. So the roots of "intelligence community" go back at least 500 years.

Andrew Hammond: For the listeners, as well, so these 18 agencies, so just help them understand how that all fits into the government. So there's a certain amount that are in the Department of Defense. There's certain ones that are civilian, that report to our Secretary, our Cabinet Secretary. There's ones that report to the President. Help our listeners understand where all of these -- where all of these agencies go back to? Where do they flow back to in terms of the government?

Barry Zulauf: You know, this is part of the problem. Why we -- why community is maybe too strong a word. More like coalition.

Andrew Hammond: Confederation.

Barry Zulauf: Confederation. Yeah. Most of the agencies are inside the Department of Defense as we've said, and that helps because that's very clear. Their responsibility is providing intelligence to the military leaders of the United States. They are mostly military organizations, though not entirely. Some civilians work in them. They have a military chain of command. Their responsibility is to provide -- the term is combat support, combat support intelligence to military entities. And that's -- all the Armed Services have their own intelligence organizations. The newest one is now Space Force. I thought that they were going to call it, you know, like Starfleet Intelligence. But they didn't. They ended up calling it space -- Space Force Intelligence. So that's the vast bulk of the intelligence organizations. Then there are what we'll call departmental organizations. That's in places like Treasury Department, for example, is responsible for dealing with monetary policy inside the United States. It's a regulatory agency, and there's a very small office, a few hundred people, Treasury Office of Intelligence Analysis. And so, Treasury has one like that. State Department has one like that. There's two inside the Department of Justice. DEA I mentioned. FBI is the other one. Those organizations are amphibians. Let's call it that way. They have a departmental role to serve the Secretary or and the Justice Department, the Attorney General, and also, they respond to the rest of the intelligence community, and I'll get back to the top leadership in just a second. The odd one out, they would probably object to me calling them odd, but anyway, CIA does not belong to either the Defense Department or any other department. There's no cabinet secretary that CIA reports to. They report by law, especially for clandestine operations, to the President of the United States directly. So that's a mess. That's eighteen different organizations, and they all are pulled together since IRTPA, that I mentioned before, the Intelligence Reform and Terrorism Prevention Act, to an organization called ODNI, Office of the Director of National Intelligence. It's a -- we say it's small. Some people think it's too big. It's about 2,000 people. It's the staff that's responsible for formulating the intelligence budget, the National Intelligence Strategy, integration across all the different agencies. Then the head of that is the DNI, the Director of National Intelligence. Currently, that's Avril Haines, the first female Director of National Intelligence. She is a direct appointee from the President of the United States, and she sits in the Cabinet of the United States. So she's co-equal with the Secretary of Defense or the Secretary of State, whatever the case may be. So that's how we're all pulled together from various different threads that are pulled together from different cabinet agencies.

Andrew Hammond: Just for our listeners, so you mentioned 2004. You mentioned the Office of the Director of National Intelligence. Can you just briefly tell listeners how much that ties into the 9/11 Commission Report.

Barry Zulauf: Well, it grew -- it grew directly out of the 9/11 attacks in the United States, which were seen as an intelligence failure, the failure of the intelligence community, a member of "intelligence community" to be able to pull together all the different bits and pieces of intelligence that we might have had leading up to 9/11 and the -- potentially the ability to prevent 9/11 attacks from happening. That's another argument we can have, whether that -- whether it was actually preventable or not, but there was a commission, a Blue Ribbon Commission, called together to examine that problem and see what can be done to fix it. Sort of parallel to that, shortly thereafter, there was another Commission, the Iraq WMD Commission. WMD is Weapons of Mass Destruction. As listeners may remember, when the United States and allies went to war in Iraq, a big part of the excuse for that was we thought that there were weapons of mass destruction in Iraq, and that was based on intelligence that was provided to the government and also shown to the Congress, who voted to support the war and shown to the United Nations in a very visible presentation by Secretary Powell, where he laid the intelligence information out. Very, very similar to what was done by then-UN Ambassador Stevenson in 1962, laying out the case for the Cuban missile crisis. You know, showing the images of the missiles. Clear that the architecture of the room and the sort of choreography was very similar. Clearly, they were trying for that same sort of effort. The trouble was, the intelligence information about weapons of mass destruction in Iraq was not nearly as firm as it would have liked to have been. There was a, you know, mistake there in being able to specify what the sources were, how reliable they were, how many sources we were. So for those two reasons, those two commissions, the 9/11 Commission looking into the failure to predict 9/11 and the WMD Convention not getting the intelligence right on weapons of mass destruction in Iraq or lack -- or lack thereof. Each one of those said we need to have over and above, the Director of Central Intelligence, who, since 1947, was both the head of CIA and the leader of the intelligence community. We need to separate those jobs. Leave CIA to be CIA, and have a separate person whose responsibility is just bringing the intelligence community together. It was -- it was too much of a -- it was too much of a job for one man. John McLaughlin, former Director of Central Intelligence and the 2004 Acting Director of Central Intelligence in the 2004 time frame -- a fraternity brother of mine, by the way. He told me once, "You know Barry, I spend 50% of my time briefing the President of the United States. I spend the other 50% of my time running CIA, and I spend the other 50% of my time leading the intelligence community." It's just too big a job for one person. So that -- so that was -- that was separated. That's why there's a Director of National Intelligence whose job is to lead the whole community and let CIA manage human intelligence, clandestine operations, and all source intelligence analysis. And the DNI now has the responsibility for pulling everything together and reporting directly to the President. [ Music ]

Andrew Hammond: You have just heard Barry speak about how in 2003, then-Secretary of State, Colin Powell, echoed an earlier presentation by then-U.S. Ambassador to the United Nations, Adlai Stevenson in 1962. Stevenson, a two-time presidential candidate, said to the Soviet Ambassador, Valerian Zorin, "I want to say to you, Mr. Zorin, that I do not have your talent for obfuscation, for distortion, for confusing language, and for double talk, and I must confess to you that I am glad that I do not. " "Well, let me say something to you, Mr. Ambassador. We do have the evidence. We have it, and it is clear, and it is incontrovertible. And let me say something else: Those weapons must be taken out of Cuba." Stevenson was of course, referring to what would become known as the Cuban Missile Crisis, the attempt by the Soviet Union to place nuclear weapons on the island of Cuba. Stevenson went on: "All right, sir. Let me ask you one simple question: Do you, Ambassador Zorin, deny that the USSR has placed, and is placing, medium and intermediate-range missiles on sites in Cuba? Yes or no? Don't wait for the translation. Yes or no?" Zorin replied "This is not a court of law. I do not need to provide a yes-or-no answer." Stevenson followed up. "I want to know if I understood you correctly. I am prepared to wait for my answer until hell freezes over if that's your decision, and I am also prepared to present the evidence in this room." Stevenson then went on to present a series of photographs proving that the Soviets were, indeed, intending to place offensive weapons on the island of Cuba. We shall pick up this thread in the second interlude. [ Music ] [ Typing ] So we've had a guest on previously, and they were saying, you know, after 9/11, the FBI came into the intelligence community, but actually, there's a bit more to it than that, isn't there? The specific changes that happened, but there's certain things that are already in place. Can you just help our listeners understand this with regards to the FBI?

Barry Zulauf: FBI goes back to 1908, right, the Bureau of Investigation. And it had been responsible for counterespionage and counterintelligence for the for the whole government during much of its existence. It did so, and I hope I won't offend my FBI friends when I -- when I say this, but for clarity, I'm going to say that it did so primarily as a reactive police organization looking for a violation of a crime, investigating it right? So someone was carrying out espionage against the United States. We discovered that. We investigate it. We take that person into court and get that person arrested. Reactive, right? One of the -- and one of the other things that came out of 9/11 was just mentioned in the WMD Commission report? No, it was just a 9/11 was FBI needs to modify itself from being just a -- and again, apologies, reactive police organization to a proactive intelligence organization. To do more, to look toward the future, to try and identify threats, counterintelligence threats, or since 9/11 in particular, counterterrorism threats, before they happen. And that required something of a cultural and organization -- a massive organizational and a considerable cultural change on the part of FBI to create an intelligence service. They had an intelligence branch inside FBI from -- from the -- from the beginning, but their responsibility was supporting law enforcement investigations primarily and including counterespionage and counterterrorism investigations. They had to learn from the rest of us in the intelligence community, more specific ways to be proactive, forward leaning, sharing information better, do some forecasting, which they really, really weren't used to doing. Then they established -- it went by various names, the National Security Branch, Intelligence Branch. It changes and gathered leadership and training and help and education from the rest of us. In the immediate 9/11 period, only that intelligence branch, whatever it was called, was inside the intelligence community, and it was a small part of FBI. My understanding is now that FBI considers all of itself to be inside the intelligence community, at least in terms of its mission. All the money that's another way of think -- we didn't talk about money, but we talked about organizations. If I can go back for a second. Some organizations, like CIA, get all of their money from the intelligence budget, and it's all classified. It's passed by the Intelligence Authorization Committees. Other organizations like DEA, DEA gets most of its money from the regular Justice Department, unclassified appropriations, the tiny bit that's inside the intelligence community that classify money. So as far as I know, the FBI, their intelligence branch, that's the only part that's funded by intelligence money. The rest of it is ordinary Justice Department money. But my understanding is they -- they consider themselves in total now to be part of the intelligence community.

Andrew Hammond: And when you mentioned cultural change there, culture is always a very difficult thing to change. So I'd be interested to hear more about your role in bringing the DEA into the intelligence community. So maybe we could go into that to give us an example of how this type of thing happened. So I believe that it became the 16th member. What was it previously? Is it similar to the FBI that you just spoke about in the sense that, of course, it always utilized intelligence for law enforcement purposes, but it was mainly preventative. Now it's more proactive. Yeah. Help us understand why it was brought in, how it was brought in and -- and all of the mechanics and logistics of this.

Barry Zulauf: Well, any law enforcement organization, whether it's the sheriff's department on a local basis or a federal law enforcement organization, to be successful, has to rely on intelligence. You have to figure out where the bad guys are. I mean, at minimum. And it could be a small intelligence capability, or it can be a large one, right? It depend -- depending on the size and the focus. DEA, Drug Enforcement Administration, just like any other law enforcement organization, we have to have intelligence. Who are the drug dealers? Where are they coming from? What kind of drugs are they? Where is the money going? In order to -- in order to -- to prosecute the criminals and bring them to justice. That's the issue for law enforcement. The all -- the focus, and including the DEA's focus, is we want to put drug dealers behind bars. So if somebody breaks the law, they sell drugs, they get arrested. They get taken to jail. That was the -- that was the whole purpose. Now I came to DEA in 1996 from Naval Intelligence, and they brought me over because they wanted someone -- they -- DEA. They wanted someone who could speak to the intelligence committees in the Congress about intelligence issues, which is what I did. So I talked to members of Congress and staff about the information that DEA was able to bring to the fore, and we used information to prosecute drug dealers. But we also found information -- by the way, we weren't looking for it, but by the way, where drug money was going to support terrorist organizations or where individual terrorists would own shipments of drugs. Osama bin Laden, himself, owned some shipments of drugs coming out of Afghanistan to the West. And we were able -- we knew from an intelligence perspective, that there was a significant overlap between drug law enforcement and terrorism, but it wasn't DEA's responsibility. It wasn't our mission. DEA, at that time, wasn't part of the intelligence community, just wanted to be a law enforcement organization. So I was trying to proselytize about that for a while, and no one wanted to -- no one wanted to do anything about it. The incident -- the beginning of what led to DEA coming into the intelligence community was on September 12, 2001. Listeners may remember that telephone service was down, for quite some time, in the Washington D.C. area. My cell phone, surprisingly, rang on the morning of September 12th, and somehow this was the General Counsel and the Chairman of HIPSCI, House Intelligence Permanent Select Committee on Intelligence, somehow were able to get a call through to me. They said, well, okay, you know, we need to do something about what you've been telling us about drugs being used to fund terrorism. Yeah, I think you're right. And it's time to push now to get DEA into the intelligence community, and I agree. I mean that -- that was -- that was the right thing to do. So that was September 12, 2001. That's -- you mentioned cultural change. Nobody wanted to do that in DEA. The special agents didn't want to do it. They want to put people in jail. General Counsel didn't want to do it because they didn't have -- have the legal authority to do it. The CFO didn't want to do it because it would complicate his mission of being able to just get a single stream of funding. The facilities people didn't want to do it because they knew they would have to build a secure facility in -- inside DEA. Everyone come up -- came up with all kinds of objections to why, why we shouldn't do this. That's why it took from September 12, 2001, until February of 2006 to get it done. Because we had to overcome all of these cultural objections. By the time 2006 came around, we were the 16th, and at that time, the smallest organization inside of the intelligence community. I was the first chief, acting chief. And they used to call me Mr. Twelve, because we had $12 million. That's an unclassified number, which is a tiny amount of money for the intelligence budget. That's all we were.

Andrew Hammond: Wow. So like, let me back up for one second. So who is the chairman on September the 12th, 2001, that phoned you?

Barry Zulauf: Porter Goss.

Andrew Hammond: Porter Goss, okay.

Barry Zulauf: He became the head of just CIA, the Director of CIA, and this is after the creation of DNI. So he was not a DCI --

Andrew Hammond: He's the very first who's not DCI, who's just director of the CIA, right?

Barry Zulauf: Right.

Andrew Hammond: Yeah.

Barry Zulauf: Yeah.

Andrew Hammond: Yeah, wow. And tell us a bit more about your current position. So Defense Intelligence Officer for Counternarcotics, Transnational Organized Crime, and Threat Finance. Help our listeners understand that, but the first part is Defense Intelligence Officer. Yeah. What does that job entail? Who do you report?

Barry Zulauf: Again, I'm again in my personal capacity not --

Andrew Hammond: Yeah, for sure, yeah.

Barry Zulauf: But, so, at the national level, there are national intelligence officers and they -- they report directly to the Director of National Intelligence. And they are geographically focused, and some of them are -- are functionally focused. Like there's one for Russia. There's one for China. There's one for terrorism. There's one for emerging technologies. Those are national intelligence officers. You can go to Intel.gov; Who We Are. That's a little button that you can click on, and it will -- it'll show you what the dividing line is. So not every country has one. Those are national intelligence officers. Now the defense enterprise, which, as I said, is, you know, three-quarters of the of the intelligence component, also has defense intelligence officers that are responsible for pulling together information. Some of them are regional. Some of them are functional. The Defense Intelligence Officer for Counternarcotics, Transnational Organized Crime, and Threat Finance, by the way, is one of the functional ones. For 25 years, the government has been largely focused on chasing Salafi terrorists around the world. So, and kind of looking the other way about counternarcotics. That's changing now. There's renewed focus on counternarcotics, in particular on fentanyl, f-e-n-t-a-n-y-l. And 70,000 people in the United States every year die from fentanyl overdoses. That's more than kidney disease. That's more than traffic accidents. It's as if there was another 9/11 every week to 10 days in the United States. That's a national security threat, and it's on the basis of chemicals that are brought into the United States from China, precursor chemicals, manufactured into fentanyl inside Mexico, and then smuggled into the United States. That's what makes it a foreign concern, not just a domestic law enforcement concern. So the reason I'm being sent there, precisely right, because of where I came from, because I came from DEA. I have that background. I can speak cop, as they say. I can speak Navy. I can speak defense. So, the task would be to be able to pull -- build bridges, pull together organizations, law enforcement organizations, military organizations who don't necessarily want to work together well, but this is going to be another challenge I need to convince them that, yep; this is important to do this. Seventy-thousand people a year is horrendous, and we need -- we need to do something about that.

Andrew Hammond: So what does being a Defense Intelligence Officer entail? Do you have an office and people working for you as -- how do you spend a lot of your time?

Barry Zulauf: So spending a lot of time talking to people, building bridges, visiting other organizations. I'm a -- I'm a big believer, even during COVID to the extent that I could, going places and seeing people face to face to be able to talk about ideas; to be able to share thoughts for how we can bring disparate bits of information together and try and come up with a solution. Just fentanyl, just this one drug, that involves diplomacy with the Chinese. That involves dealing with Chinese companies trying to figure out which ones are sending -- sending the -- the chemicals. It involves dealing with the shippers who put the -- who run the container ships that go back and forth across the North Pacific. It's dealing with the Mexicans at the diplomatic and law enforcement level. It's border control, because the stuff gets smuggled across the border into the United States. And then, on and on, through distribution inside the United States on down to, you know, public health issues. It's an enormous, enormous problem, and no single organization, even as big as the Defense Intelligence enterprise, can deal with it alone. So it -- it's going to be a lot of diplomacy and a lot of building bridges, convincing people to do the right thing.

Andrew Hammond: So let's move onto your time at ODNI. So tell us what being the ODNI reference for the center, for the studies in intelligence, what did that entail? >> Yeah. So that's my previous job I had for a year before going over -- over to DIA. So CIA, Central Intelligence Agency, has an organization called the Center for the Study of Intelligence that dates back to the 1950s, and it's a remnant of when CIA, headed by the director of Central Intelligence, ran the whole community. So this is -- it's a think tank that does lessons learned. It looks at future trends. There's an oral history program, and there's a -- there's a sort of a written history program, and also, the museum. CIA has an excellent museum. Unlike the Spy Museum, where anyone can come here, the CIA's Museum, unfortunately, is -- is behind gates, guards, and guns. You have to be able to get into the CIA to get there, but trust me it's an excellent museum. There the referent term is a -- is a term of art. That is, a person who's identified from another organization to be able to represent that organization's equities at the Center for the Study of Intelligence. Most of those, in fact, all of those, other -- other than yours truly, are from various parts of CIA. There have been, from time to time, people coming from other -- other agencies. So the purpose for that is, all right, so here's a question about intelligence in Africa. There's a referent from the Africa Center in CIA. So that person would be responsible for going to the organization and trying to find the people responsible, pulling together the information, you know, writing it up and being able to take that forward. My role for the past year has been as the ODNI referent. So anything that has to do with ODNI leadership of the intelligence community, intelligence integration; you know, pulling those, those -- those sorts of issues, the thing that I've been talking about. The person that that does that -- so my -- a better explanation would be I'm the ODNI historian. Term of art is -- is referent. So some of the things I get to -- I get to do, I mean, I get to meet all the incoming employees, and I get a whole 45 minutes with them to be able to talk, you know, 400 years of intelligence history in 45 minutes. To give -- give them a sense of why the organization looks the way it does, where we came from, explain the legislation that underlies ODNI. Give them a brief walk through the museum. So this is everybody that joins the CIA or everybody that goes to the ODNI?

Barry Zulauf: ODNI.

Andrew Hammond: Okay.

Barry Zulauf: Yeah. Most, if not all, organizations have a similar function for themselves. I don't think they all have a historian briefing them, though. CIA does. I know, because I watch them. I watch them do their -- do their onboarding is what they call it. I'm a professional historian, and I find that Americans are among the most ahistorical people in the world. We either actively do not care about history, where we came from, or if we know a little bit about it, it's often -- it's often wrong. And that's -- that's a terrible problem. I think that leads to a lot of mistakes that we -- that we make where we don't know our history. We can't learn from our history, and we're doomed, George Santayana, had the famous quotation. Right? If you -- if you don't know your history, you're -- you're doomed. You're doomed to repeat it. I would amend Santayana's quote: If you don't know your history well, you're doomed to repeat it. I've often seen people draw inappropriate historical parallels. So I'm trying to fix that a little bit by identifying where we've come from as an -- as an organization. [ Music ]

Andrew Hammond: In the last interlude, we spoke about Adlai Stevenson's famous speech before the UN in 1962. Fast forward, 40-odd years, and Colin Powell would address the UN in the run up to the US invasion of Iraq in March 2003. "My colleagues, every statement I make today is backed up by sources, solid sources. These are not assertions. What we're giving you are facts and conclusions based on solid intelligence." He was referring to Iraq's WMD, or weapons of mass destruction, program. That is, nuclear, biological, and chemical weapons. Powell continued. "Ladies and gentlemen, these are not assertions. These are facts corroborated by many sources, some of them the sources of the intelligence services of other countries." Secretary Powell was probably the most trusted member of the George W. Bush administration globally. So the fact that he put his reputation on the line to provide a rationale for the war convinced many people. There were, in fact, however, no weapons of mass destruction as he had claimed. An interesting postscript to these two interludes is that in 1962, Ambassador Zorin was in the dark. He hadn't been kept in the loop with regards to offensive missiles in Cuba. The year before, meanwhile, in 1961, what is often forgotten is that Adlai Stevenson again went before the United Nations, but this time to state that the U.S. had, in fact, no involvement in the Bay of Pigs invasion of Cuba that year. But, in fact, it had. Later that day, he would state to a friend. "I did not tell the whole truth. I did not know the whole truth." And he worried that, "My credibility has been compromised." Powell, meanwhile, had wanted to vet the intelligence for his speech himself. This leads to many other questions which we don't have time to go into within the scope of these two interludes. There's no great takeaway here other than the next time you see a policymaker or ambassador at the UN, make a speech in the middle of a major crisis, think about how much they really know, and think of Zorin, Stevenson, and Powell. [ Music ] [ Typing ]

Barry Zulauf: Part of what I do is, as President of IAFE, the International Association for Intelligence Education, we did some research, and we called it Project Universe. It's somewhat conceded on our part. That we wanted to know. It started with a question: Well, what's the total universe of -- of universities that we're looking at? So I have a spreadsheet, and also, we're in the process of expanding that now to other countries. It's not going to be nearly that many. IAFE, International Association for Intelligence Education. Our website is iafie.org, if anyone wants -- wants to look at that. We are almost, quite literally, every intelligence educator in the Western world. From Poland to New Zealand, from Japan to South Africa, 400 of us. It's a lot, and there -- there are some people who work in the field of intelligence who do not belong to IAFE, but that that -- that's fine. You know, they're superstars on their -- I won't name names. I won't embarrass anyone. But you know, it's they -- they feel they don't need us. But one of the things that we do is provide, as a service, this kind of information where the schools are. And if anyone out there is interested in pursuing a either an undergraduate or graduate-level program in intelligence analysis, we're happy to share information. We have -- we have student members, as well. There's a big debate, by the way, Andrew, between whether an intelligence program in undergraduate school, or graduate school for that matter, is worth anything or not, and there are people who think strongly on both -- on both sides. There are people who think it's worthless because you're learning something from someone who might never have been in the intelligence community. It's probably wrong anyway, and anything that you learn about how intelligence analysis is done, I'll have to unteach you and teach you my way of doing things. That's one extreme. I don't share that view. There's another view, another extreme view, is that if you don't have an education in intelligence studies, you're no good as an intelligence analyst. You have to do it through a university education, and, oh, by the way, it has to be mine because, you know, mine is the best program. I don't share that view either. I think -- I think there's a mix. There's a place in the intelligence community for people who come from Mercyhurst University with a degree in intelligence. There is room for people who come into the intelligence community with a degree in data analytics from Penn State University, and they can't spell intelligence, but they know how to do data and everything in between. I am -- I do think that, based on my own personal experience, I was not able to get any of this when I was an undergraduate or a graduate student. In fact, in the 1970s and 80s, there was a strong bias against the intelligence community among academics. The one time I caused my PhD advisor to cry, literally cry, was when I told him that, you know, I'm not going to go into academia. I'm going to go into the intelligence community, and he teared up because he was a leftist, you know? "Why are you going to do that? You have such a great mind. You're going to go to work for those bastards?" But that's what -- that's what I wanted. So the existence of intelligence education programs in places like Mercyhurst or Johns Hopkins, or wherever they may be, can give people, early on in their career, knowledges and experience that I wasn't able to get in academia when I when I was growing up. So I like to think when I teach at these places that I'm helping people avoid a lot of heartache that they don't have to go through this. They'll know what it is, and we -- there are also people who come into these programs. They want to be James Bond or they want to be Jason Bourne, and for anyone that's out there, there are a few James Bonds. There are a few Jason Bournes, but not many of them. If you really want to know what life is like in the intelligence community on a day-to-day basis, watch The Office. That's a lot more what it's like. So if you -- if you aren't interested in dealing in a bureaucracy with quirky human beings, you're probably in the wrong -- in the wrong business. So I've steered some people away -- away from professions in intelligence, as well.

Andrew Hammond: So can you just tell us a little bit more about your -- your time in the Navy? So 22 years, so were you full-time, part-time, reservists? Did you join up to do intelligence in the Navy from your PhD?

Barry Zulauf: Well, I knew I wanted to do the Soviet Navy, which in the -- that sounds -- there's no Soviet Union now. So what's so important about that? In the 1970s and early 1980s, that was the thing, right, that I wanted to do. That's what made Bernie Morris cry, because I wanted -- I wanted to go to work for Naval Intelligence. So that -- that was my first job as a civilian in Naval Intelligence. I spoke Russian. I did my dissertation on Soviet foreign policy and that -- that's really what I wanted to do with my -- with my life. So I started as a civilian. Then I was -- this is going to -- sounds like a joke, a professor and an Admiral walk into a bar. Right? So I was working for the then-Director of Naval Intelligence, DNI, the real DNI, as we like to say, and we were coming back from a ship visit to the then-Soviet Union. We walked into a bar, and he was talking to me, and so, I looked the part. But I had the short haircut and everything, and he asked me so where did you do your military service? And I said I have never been in uniform, Admiral. And he looked at me like I had fallen off a turnip truck. And really? And he called his aide over and whispered something into his aide's ear, which I couldn't -- out of earshot, and his aide took out the little black book -- booklet -- notebook. That's never good, by the way. Right? And so, when I got back to my office, there was an order on my desk. You will report to -- to Naval Processing Center Baltimore -- or I'm sorry -- Military Entrance Processing Center, Baltimore and got a -- got a commission as -- as a reserve officer in in the Navy part time, right, which was absolutely fantastic, because I was a civilian working for Naval Intelligence. Now part time, you know, weekends and two weeks in the summer, I'm going to be in the Navy. My Naval Intelligence bosses thought this is fantastic because he's going to learn what the Navy actually is. The Navy bosses thought it was fantastic because they've got somebody, a strategic asset, who's on the Admiral's staff. Everybody's happy, and whenever I asked for opportunities to take time to go on a -- on a -- on a reserved tour somewhere, everyone said yes, yes, yes, go, go, go; enjoy it. And I learned a lot how to be a naval officer and be a better -- a better intelligence officer as a result of that. Including up into when, as a 50-year-old reserve officer, I volunteered to go on active duty to go to Afghanistan, as they needed -- they needed targeters to be able to target insurgent leaders. So I volunteered to be able to do that. I'm not sure what motivated -- no, I am sure what motivated me to do that. Because I knew that it was a -- it was a mission that needed to be done. They didn't have the people with the right skills in order to be able to do that. And if I can go there as a naval officer, then some army colonel who can actually break things can go out in the in the countryside and use, you know, military force better than -- better than I could. And it was a great opportunity. I got to go so many places, above the Arctic Circle, all around the world, in and out of uniform. And it was a great opportunity to be able to serve.

Andrew Hammond: And did you ever get to go to Murmansk?

Barry Zulauf: Yes.

Andrew Hammond: Yeah. I've been there once. It was kind of weird because the local radio station gives you a daily radiation report, just like you get a daily weather report. Interesting place.

Barry Zulauf: Yes. I've been there. I haven't seen you. Okay, so another short story. So I was there over 4th of July. The Soviet Union was still in existence. It was -- it hadn't quite fallen apart yet. So we were there on 4th of July, and the Northern fleets decided they were going to have a BBQ for us Americans, and it was going to be on a -- it was on the Kirov, which we discovered at the -- was no longer able to operate at the time. It couldn't operate because the propellers, the screws, had been sent back to the machine shop for repair, and some criminal elements had taken them, melted them down for scrap metal and sold the screws. So Kirov was not able to move. So we had to go out there. They were hosting us for a BBQ 4th of July at midnight. Now it's above the Arctic Circle. So the sun is still shining. The midnight sun, 4th of July. It's snowing. They're giving us a proper American cookout with hot dogs and hamburgers on the deck of a Soviet missile cruiser, and the Northern Fleet band is playing God Bless America at the same time. What a -- what a study in contrasts.

Andrew Hammond: Wow, well, that must have been quite an experience.

Barry Zulauf: That was fun.

Andrew Hammond: And just as a final question, is there anything that you would like to pass onto our listeners? Was it 37 years in intelligence now?

Barry Zulauf: Thirty-seven years.

Andrew Hammond: So is there -- is there anything that you would pass onto them or any -- any words of wisdom from 37 years in the intelligence business?

Barry Zulauf: Yes. So intelligence gets a bad rap these days, I think, and it's somewhat deserved, somewhat -- somewhat undeserved. We get accused of somehow being unamerican or that we're that we're undermining civil liberties or something like that, and it's really not deserved. Intelligence exists as a great function of state. In the West, we're the only great function of state that only exists for the reason to tell bad news to the boss. Or to tell the boss something that he or she doesn't want to hear. Everybody else is inherently political. They want -- the Navy goes to see the President of United States. They want another aircraft carrier or everybody wants something. Now we do have opportunities when we go to our congressional committees, as you mentioned. We want money, right? We want our budget. But every other time when we're giving substantive intelligence, we don't want something. We don't have an agenda. We exist for the purpose of providing objective and unbiased intelligence on the basis of the best information that we can come up with on the basis of analysis and forecasting to the best of our ability, given -- given our training. And no matter what that is, to give it to the decision maker, even if it's not what they don't want to hear. Even if it's well, sir, your favorite program is not going to turn out the way you think it's going to turn out. And these are -- these are the reasons why. And that's a vital function to keep our republic operating. Somebody has to be able to do that, to tell decision makers what they -- what they don't want to hear. And if the intelligence community doesn't do it, nobody else is going to. Everybody else is either validly partisan. I mean Republican/Democrat partisan, or biased in some way, plus or minus whatever their institutional requirement is. And it's an -- it's an honorable profession. I'll leave you with a last thought. I have three kids. They're all in their 20s now, and I remember them asking me when they'd seen me put on my uniform and go to work on a weekend, they'd asked me. "Daddy, are you a good guy or a bad guy?" And I've always been able to tell them I'm a good guy. So that's what I would want to leave listeners with.

Andrew Hammond: Well, thanks ever so much for your time and for passing on your expertise and experiences in the field. Thank you.

Barry Zulauf: Well, thank you, Andrew. It's been -- it's been a lot of fun and -- and thanks to everybody for hanging out with me. [ Music ] [ Music ]

Andrew Hammond: Thanks for listening to this episode of SpyCast. Please follow us on Apple, Spotify, or wherever you get your podcasts. If you have feedback, you can reach us by email at spycast@spymuseum.org or on Twitter @intlspycast. If you go to our page at thecyberware.com/ podcast/spycast, you can find links to further resources, detailed show notes, and full transcripts. I'm your host, Andrew Hammond, and my podcast content partner is Erin Dietrick. The rest of the team involved in the show is Mike Mincey, Memphis Vaughn III, Emily Coletta, Afua Anokwa, Emily Rens, Elliott Peltzman, Tré Hester, and Jen Eiben. This show is brought to you from the home of the world's preeminent collection of intelligence and espionage-related artifacts, the International Spy Museum. [ Music ]