CSO Perspectives is a weekly column and podcast where Rick Howard discusses the ideas, strategies and technologies that senior cybersecurity executives wrestle with on a daily basis.

Introducing the cyberspace sand table series: The DNC compromise.

When I was a young captain in the U.S. Army, I was the signal officer for a field artillery battalion at Fort Polk, Louisiana. That’s the same Fort Polk that the Army created back in the early 1940s to train its famous commanders (Eisenhower, Clark, Bradley and Patton) and the soldiers that served them, to get ready for WWII. Camp Polk, as it was known back then, was a real-life physical training environment where military units could actually maneuver on the ground, make mistakes, and make adjustments to correct those mistakes, before the bullets started flying for real in Europe.

As a field artillery signal officer in the 1980s, I was in charge of all the communications systems among the five battery commands, the battalion staff elements (admin, logistics, operations, and intelligence) and the higher commands at the brigade and division levels. By then, the Army had moved its training environment to Fort Irwin, California, at a place called the National Training Center (NTC), and they routinely ran all of its units through there to get evaluated.

Your career was made there. If you did well at NTC, regardless of your position, you were likely to get promoted. If you didn’t, well, there were plenty of insurance and car sales positions open just outside the base. As my editor, John Petrik, says, "The Carthaginians used to crucify unsuccessful generals. We make them sell real estate."

On our trip to the NTC, after two weeks of hard training, we were on our last task. We were supporting an infantry brigade on a night mission defending the back end of a valley with two mountain ridges on both sides. We knew exactly where the enemy was going to attack us from, right down the valley’s middle, and we deployed many devious surprises designed to convince them to turn around and run away. We were ready.

And then, we were overrun. At zero dark thirty on the second night of the defense, I was startled awake from my sleeping cot as enemy tanks and personnel carriers drove around and through our position. All of our MILES equipment (“multiple integrated laser engagement system”—think laser tag for Army people) lit up like a Christmas tree. We were all dead and we had no idea how the bad guys got through our defenses.

Hours later, blurry eyed at the NTC evaluator’s “Hot Wash,” all the battalion leadership gathered to get our collective butts chewed and to discover what we did wrong. The briefing officials directed our attention to a sand table stood up in front of the tent. It was a three dimensional model of the valley we were supposed to defend complete with all of our weapon systems placements and those devious surprises we were so proud of. And then we all saw it, collectively, at the same time. There was a skinny dirt trail that ran alongside the valley’s left mountain ridge that we all had completely ignored. The commander of the NTC world class opposing forces (OPFOR) drove a brigade of tanks and infantry, single file, down that trail. The side of the ridge we were on totally screened their noise and movement. They popped out of the trail on our brigade’s left flank, without opposition or early warning, and rolled up our side. The fight was over in 20 minutes.

For me, the good news was, despite everybody being dead, all the radios continued to work. So, I had that going for me.

Cyberspace sand tables.

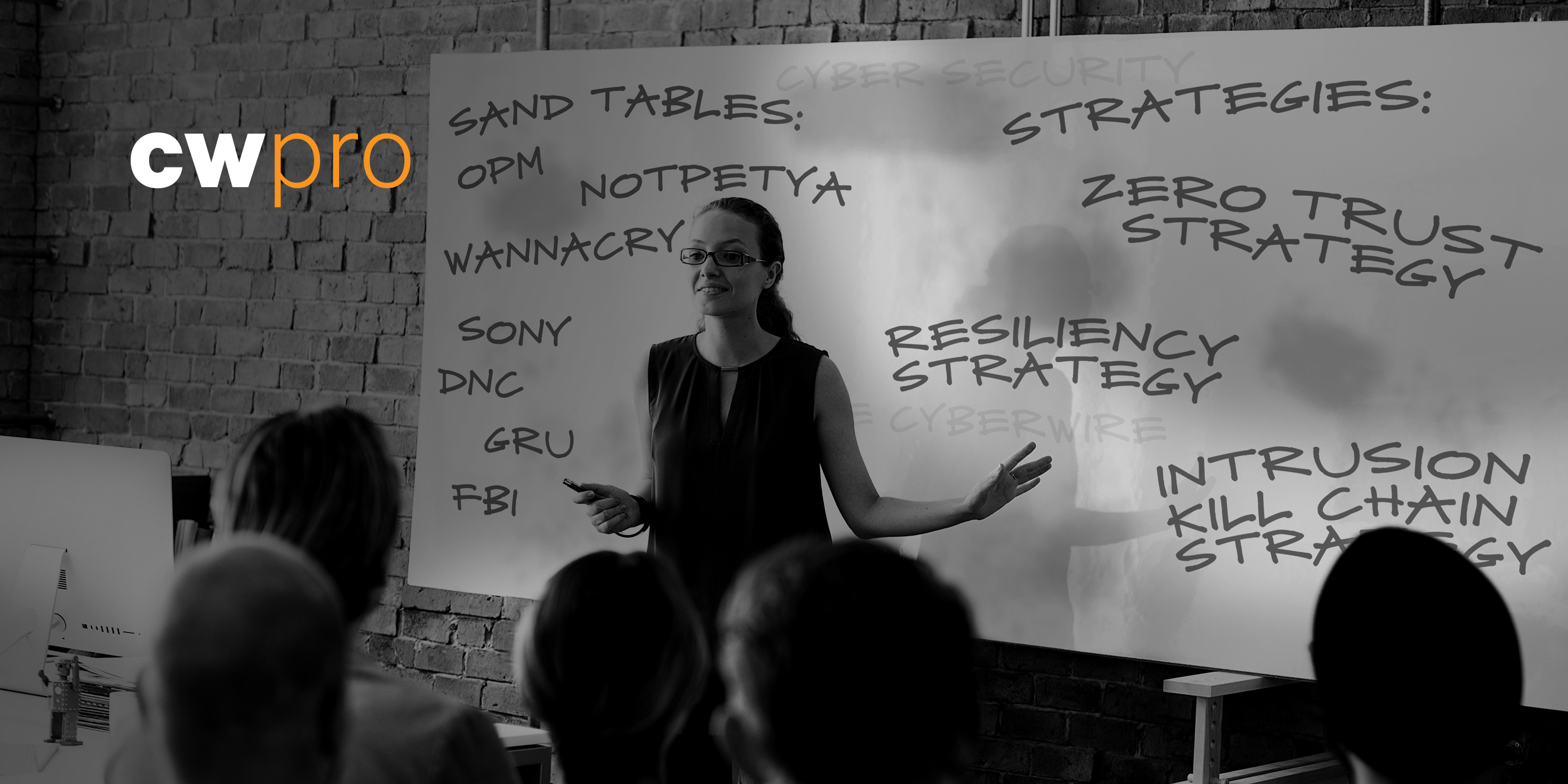

All of this is a long story that has nothing to do with cybersecurity except for the sand table concept. One thing we all should be doing is adapting that technique to improve our own cyber defenses. It doesn’t have to be anything fancy like a big physical model inside a giant and dusty tent. It can be done by simply analyzing famously known cyber attacks (like OPM, notPetya, WannaCry, and Sony) across the intrusion kill chain, and comparing our defenses against how the adversary actually succeeded. Military planners do this all the time with famous battles like the Battle of Waterloo (1815) and the Battle of Gettysburg (1863).

In my NTC example, the sand table crystallized essential defensive problems that we didn’t learn from conducting our own physical recon of the area and reviewing the associated contour maps. Maybe we at least should have been watching that left side of the ridge for early warning. Perhaps, we should have had a contingency plan in the unlikely case that a crazy OPFOR commander would send his forces, single file, down a treacherous dirt path at night to get on our flank.

I believe we can use cyberspace sand tables in a similar manner and we can use the intrusion kill chain model to help us move the pieces around the board.

That’s what this series is about. Every once in a while, I'm going to review an infamous cyber attack that has been in the news to see how the adversary pulled it off. Then I'm going to look at our first principle strategies to see if they would have defeated the adversday’s playbook. If not, we might have to make some adjustments to our first principle strategies or maybe even invent new ones. We’ll cross that bridge when we come to it. But let’s start with one of my personal favorite cyber attacks: The Democratic National Committee hack of 2016.

Setting up the sand table.

The U.S. Democratic Party’s operating arm has been the Democratic National Committee (DNC) since 1848. The DNC established the Democratic Congressional Campaign Committee (DCCC) to oversee the efforts to elect Democrats to the U.S. House of Representatives roughly 20 years later. In the spring of 2016 though, Secretary Hillary Clinton was the presumptive democratic candidate for the office of the United States President and John Podesta was her campaign chairman.

Sadly, the security of the DNC network was amateurish at best. From David Sanger’s interview of Richard Clark in The Perfect Weapon: War, Sabotage, and Fear in the Cyber Age, despite the past history of the Watergate break ins in 1972 and Chinese and Russian cyber intrusions into the Obama campaigns in 2008 and 2012, the DNC “was securing its data with the kind of minimal techniques that you might expect to find at a chain of dry cleaners.” They did have an anti-spam service, but it wasn’t a good one. According to Sanger, the DNC “... lacked any capability for anticipating attacks or detecting suspicious activity in the network … It was 2015, and the committee was still thinking like it was 1972.” The network was a “bailing-wire-and-duct-tape organization held together largely by the labors of recent college graduates working on shoestring budgets.” It goes without saying that they didn’t have a CISO.

Meanwhile, the Russians had been experimenting with something loosely called the Gerasimov doctrine since 2013. General Valery Gerasimov, the Russian Federation’s Chief of the General Staff at the time, outlined the strategy in a speech:

- The quick reduction of the enemy’s military and economic potential by destroying critical military and civilian infrastructure.

- Simultaneous warfare on the ground and in cyberspace.

- Indirect operations (Influence Operations) to confuse and bewilder the enemy’s military and civilian populations.

In February 2014, Russia invaded Ukraine and used that country as a learning lab to perfect the techniques for the Gerasimov doctrine. From Sandworm, Andy Greenberg’s book, “In May 2014, a pro-Russian hacker group calling itself CyberBerkut (linked to Fancy Bear much later) targeted Ukraine’s Central Election Commission in order to discredit the voting system.” By 2015, the Russians launched “waves of vicious cyberattacks … [against] Ukraine’s government, media, and transportation. They culminated in the first known blackouts ever caused by hackers, attacks that turned off power for hundreds of thousands of civilians.”

Despite all the colorful adversary names that the commercial cybersecurity industry has used to describe Russian cyber adversaries for over a decade (Sandworm, Cozy Bear, Fancy Bear, the Shadow Brokers, CyberBerkut, Unit 26165, Unit 74455, and Guccifer 2.0), Greenberg followed the trails from all that collective activity back to one singular organization: the Russian GRU or Main Intelligence Directorate.

Prior to 2016, The GRU turned its attention to the U.S. Presidential election.

Turn one: red team (Summer 2015 - June 2016).

To fund their operation, the GRU mined bitcoin and laundered some $95,000 through a web of transactions using what they thought was the complete secrecy of cryptocurrencies. They also used bitcoin to pay for their command and control infrastructure and to build their social media personas: DCLeaks & Guccifer 2.0.

According to Crowdstrike, the GRU may have gained access to the DNC network as early as the Summer of 2015. But by 15 March 2016, nearly a year later, they began working their way across the intrusion kill chain and they started with recon. Four days later (19 March), they delivered a phishing message to John Podesta, crafted to look like it came from Google, claiming that someone had stolen his password and he should change it immediately. After verifying with his IT guy (the overworked and underpaid new college graduate) that the message was legitimate, Podesta clicked the link that took him to a decoy log-in page (exploitation) where he entered his credentials. Two days after that, the GRU exfiltrated (command and control, actions on the objective) 50,000 email messages from Podesta’s account.

By the end of March, the GRU had widened the aperture of their phishing campaign to other DNC staffers. On 6 April, they began delivering email with a malicious excel attachment (“hillary-clinton-favorable-rating.xlsx”) to some employees that worked for both the DNC and the DCCC. Once opened, the staffers were transported to the GRU-controlled website (exploitation) where they entered their DNC credentials. Some dual DNC/DCCC staffers adopted the bad practice of using the same credentials to log into their DNC assets as they did to log into their DCCC assets. This gave the GRU legitimate credentials to log into the DCCC.

The very next day (7 April), with access to the DCCC network now, they began to recon. By 12 April, they had gained access to the DCCC network (exploitation) and moved laterally (actions on the objective) compromising as many machines as they could. By 22 April, they had exfiltrated (actions on the objective) several gigabytes of opposition research material.

Between April and June, the GRU reconned for keywords like “Trump,” “Benghazi investigation,” and “opposition research,” exploited DCCC computers with malware installation, and exfiltrated data to servers in Arizona and illinois (actions on the objective). To obscure their exfiltration activity, the GRU bounced their data through international servers first (command and control.)

Turn one: blue team (Summer of 2015 - May 2016).

In the summer of 2015, eight months before the DNC noticed that they were under attack, The National Security Agency (NSA) notified the FBI of Russian intrusions into DNC networks. An overworked FBI agent tried to call the DNC computer security team but discovered they didn’t have one. He ended up talking to the DNC computer help desk. The help desk guy, and it was a guy, took the information but didn’t really trust it. He thought it might be a spoof. He sent a memo to senior leadership anyway. Nobody did anything about it.

By November, the FBI had more hard evidence of GRU controlled command and control traffic originating from the DNC network. The DNC tech people still didn’t trust the information and didn't tell the DNC leadership. Meanwhile, the FBI never told the white house.

By April 2016, four months later, the FBI finally established a face-to-face meeting with the DNC tech people and convinced them that the intelligence was legitimate. They also convinced them to install some security detection technology. The DNC installed Crowdstrike’s Falcon project, an endpoint detection and response (EDR) product.

By May 2016, the DNC’s EDR platform identified indicators of compromise from both Cozy Bear and Fancy Bear and the Crowdstrike incident response team began the work of ejecting that presence from the DNC network.

Turn two: red team (June 2016 - November 2016).

Between April and June 2016, the GRU gained access to the DNC’s Microsoft Exchange server and stole thousands of emails. They compromised ~33 DNC hosts including the email server and the DCCC website. The DCCC website redirected visitors to a look-alike site called actblues.com meant to mimic the popular fundraising site ActBlue. They began reconning for information about state boards of election, political parties, and in the process, compromised at least 10 DCCC computers.

By July, they had compromised the Board of Elections website for the State of Illinois and stole personal information of some 500,000+ voters. They conducted a supply chain cyber attack by compromising a software vendor (VR Systems) responsible for verifying voter registration in several U.S elections.

By October, they had reconnoitered the networks of election officials from specific counties in Georgia, Iowa, and Florida. They also gained access to the DNC’s cloud presence, created backups using the cloud provider’s technology, and then copied the backups over to the GRU’s own instance in the same cloud provider.

Before the election in November, the GRU spearphished potential victims from spoofed accounts that looked like they originated from the voter registration software company (VR Systems). The email contained word documents that presented the software vendor’s logo but was also infected with malware.

Turn two: blue team (May 2016 - November 2016).

The CrowdStrike Incident Response team started collecting intelligence on the DNC intrusions on 1 May and began formulating the ejection plan. They executed the plan on 10 June and completed their work on 13 June.

They were ready to go much earlier,but DNC leadership wouldn’t let them because the leadership was worried about on-going operations. They delayed executing the ejection plan for an entire month while the GRU forces ran around in their networks.

Eventually, they had all of the DNC employees turn in their computers and mobile devices. When the DNC gave them back, the incident response team had wiped everything clean of data and had installed brand new versions of software.

From that time on, with permission of the DNC, Crowdstrike shared its intelligence with the FBI. That said, the DNC leadership didn’t fully trust the FBI and did not allow them access to their physical servers. According to David Sanger, the only intelligence the FBI was getting was secondhand via Crowdstrike.

On June 14, the DNC went public with the information and a month and a half later (29 July), the DCCC did the same. Subsequently, the DNC Chair (Debbie Wasserman Schultz) and CEO (Amy Dacey) resigned.

The new Interim Chair (Donna Brazille) formed a cybersecurity advisory board to provide advice to senior leadership. Members included Sean Henry (Crowdstrike President), Aneesh Chopra (President Obama’s former Chief Technology Officer), Michael Sussmann (former federal prosecutor and a former partner at the law firm Perkins Coie, who focused on privacy and cybersecurity law) and others. Brazille also brought in cybersecurity expert volunteers from Facebook, Google, and Coinbase.

The DNC implemented new security measures. They required employees to log off when they left their machines and they implemented two-factor authentication. They abandoned the DNC email system and replaced phone calls for sensitive subjects with Apple’s FaceTime Audio.

Crowdstrike did miss a linux-based version of malware called X-Agent in their June sweep. They didn’t eject that from the DNC networks until October. X-Agent, also known as Sophacy, collects keystrokes on the infected computer.

Impact.

In the end, the American voters chose candidate Trump to be the 45th President of the United States. It’s unclear if the GRU’s tactical execution of the Gerasimov doctrine to influence the U.S. presidential election changed the outcome. Expert opinion on the matter differs. On the one hand, measuring causal effectiveness in marketing campaigns (influence operations) is not an exact science, especially when there are so many competing efforts trying to sway opinion. We have everything from official candidate campaign messaging to the less official political action committee activities to Uncle Kevin’s screeds on Facebook. Combine all of that with Russian influence operations and it’s a mess.

On the other hand, the election was so close. President Trump received 304 electoral votes compared to 227 that Secretary Clinton collected. Still, Secretary Clinton earned more than 2 million popular votes over what President Trump gathered. The election really came down to a handful of states that could have gone either way right up to election day. An influence operation wouldn’t have had to do much to change the outcome.

Regardless, there is one question that the DNC leadership should have been asking themselves some two years before the election: what data are material to our campaign efforts? What data, if lost, destroyed, or leaked, will materially damage our efforts? Because they didn’t choose to protect their material data (or any data for that matter), during the final days of the election cycle, they had to redirect their campaign messaging resources to rebut the negative press from the leaked Podesta email cache. I was not there, but I assume they would have preferred to stay on their positive messaging about Clinton’s platform.

Because of the GRU cyber attack, the Democratic National Committee Chair (Debbie Wasserman Schultz) and the DNC CEO ( Amy Dacey) resigned after the hacks went public. Donna Brazille replaced Shultz and in her book, “Hacks : the inside story of the break-ins and breakdowns that put Donald Trump in the White House,” said that the DNC had already spent $300 K on remediation but expected to pay out a total of $4 Million when all was said and done.

Hotwash: Things the DNC could have done.

In 2016, we should consider the DNC and DCCC as comparable to startup organizations in the commercial world. They had limited resources and a short amount of time to get their product noticed and successful. For them, their product was the Democratic candidate for the U.S. President. As with most startup leadership, they weren’t inclined to spend resources on side projects that didn’t directly contribute to the bottom line. I get it. According to Brazille, their burn rate was almost $4 million a month during that last year and they were already swimming in debt. Let’s face it. Cybersecurity was not high on the priority list.

That said, before 2015, if you would’ve asked me to estimate the probability of a material cyber attack before the election in 2016, my first guess would’ve been north of 75%. With the democratic party’s history with physical and electronic break-ins (Watergate 1972, Obama campaigns 2008 and 2012,) and the fact that they didn’t have a CISO nor any kind of detection or prevention technology in place to stop bad guys, they were an obvious and vulnerable target. The fact that nobody in the Democratic leadership—from the DNC all the way to the White House—didn’t know that is scary. I mean, I could have hacked the DNC with my crack team of seven-year-old Fortnite players. I'm just saying.

Even with the DNC’s resource constraints, some simple things could have been done early on in terms of cybersecurity first principles that could have prevented the disaster; maybe not the GRU breach but perhaps the prevention of the Podesta email exfiltration.

The first simple task that comes to mind falls under the resiliency strategy and the need for crisis planning. The very least they could have done, at no cost, would be to establish an open channel with the FBI. As the saying goes, you don’t want to be exchanging business cards with the FBI for the first time during an actual crisis. But that’s exactly what they did. And the thing is, the FBI is really good at this kind of advisory role. If the DNC had an open communications channel with the FBI, the two parties wouldn’t have wasted months (Summer of 2015 through April of 2016) learning how to trust each other. They might have been able to put measures in place in 2015 that would have prevented the success of the GRU in 2016.

The next first principle task falls under the zero trust strategy and the tactic of using two-factor authentication for employee logins. That simple preventative measure would have prevented the exfiltration of the Podesta emails and the compromises of the DNC and DCCC hosts. Even if the DNC/DCCC employee victims did unwittingly give their login credentials to the GRU, the Russian hacking team wouldn’t be able to use them easily because they wouldn’t have had access to the two-factor devices.

Finally, the last first principle task falls under the intrusion kill chain strategy. Before the DNC deployed the Crowdstrike Falcon product, they couldn’t detect the GRU in their networks even with the FBI showing them the way. After the installation, the product immediately discovered indicators of compromise for Cozy Bear and Fancy Bear, Crowdstrike’s code words for Russian cyber campaigns. Clearly, having the capability to look for known adversary behavior is an essential capability.

The bottom line is that deploying these three first principle tactics

- Talk to the FBI (Resiliency: Crisis Planning),

- Install two-factor authentication (Zero trust - Identity), and

- Look for known adversary activity (Intrusion Kill Chain Prevention - GRU Campaigns),

would have reduced the probability of material impact. How much it would reduce that probability might be debatable, but at the beginning of this hot wash, I forecast that without these measures, the probability would be above 75%. With them, I put it below 20%.

The GRU may have found a way around those measures eventually, but they would have had to work for it. And that’s with a minimal deployment of our first principle strategies. Consider a more mature deployment and how low they could have reduced that probability. The proof is in what the DNC did next for the 2018 and 2020 election cycles. They hired Bob Lord, former Yahoo CISO, to run the infosec program and by all accounts, the Russians didn’t penetrate the DNC during his tenure.

Cyberspace sand tables as a training tool.

Military commanders have used some version of a physical sand table since the world was young. They have used it because it works. And I know that some network defenders are loath to use military metaphors for cyber defense. Fine. If you don’t like the military metaphor, use a sports metaphor. Cyber sand tables are no different than your high school basketball coach drawing up plays on a white board at half time to illustrate why the other team was kicking your backside on the court. They are not different from Tom Brady watching hours of film on his opponents to get ready for the next context. Who can argue with that success? He’s won seven super bowls out of ten tries while playing on two different teams. If he can spend time at the sand table, I think we can too.

Reading list.

11 MAY 2020:

CSOP S1E6:: Cybersecurity First Principles

- Hash Table Guests: None

- Link: Podcast

- Link: Transcript

- Link: Essay

18 MAY 2020

CSOP S1E7:: Cybersecurity first principles: zero trust

- Hash Table Guests: None

- Link: Podcast

- Link: Transcript

- Link: Essay

26 MAY 2020:

CSOP S1E8:: Cybersecurity first principles: intrusion kill chains.

- Hash Table Guests: None

- Link: Podcast

- Link: Transcript

- Link: Essay

01 JUN 2020:

CSOP S1E9:: Cybersecurity first principles - resilience

- Hash Table Guests: None

- Link: Podcast

- Link: Transcript

- Link: Essay

15 JUN 2020:

CSOP S1E11:: Cybersecurity first principles - risk

- Hash Table Guests: None

- Link: Podcast

- Link: Transcript

- Link: Essay

03 AUG 2020:

CSOP S2E3: Incident response: a first principle idea..

- Hash Table Guests: None

- Link: Podcast

- Link: Transcript

- Link: Essay

10 AUG 2020:

CSOP S2E4: Incident response: around the Hash Table.

- Hash Table Guests:

- Jerry Archer - Sallie Mae CSO

- Ted Wagner - SAP National Security Services CISO

- Steve Winterfeld - Akamai Advisory CISO

- Rick Doten - Carolina Complete Health CISO

- Link: Podcast

- Link: Transcript

- No Essay

31 AUG 2020:

CSOP S2E7:: Identity Management: a first principle idea.

- Hash Table Guests: None

- Link: Podcast

- Link: Transcript

- Link: Essay

07 SEP 2020:

CSOP S2E8: Identity Management: around the Hash Table.

- Hash Table Guests:

- Helen Patton - CISO - Ohio State University

- Suzie Smibert - CISO - Finning

- Rick Doten - CISO - Carolina Complete Health

- Link: Podcast

- Link: Transcript

- No Essay

14 SEP 2020:

CSOP S2E9: Red team, blue team operations: a first principle idea.

- Hash Table Guests: None

- Link: Podcast

- Link: Transcript

- Link: Essay

21 SEP 2020:

CSOP S2E10: Red team blue team operations: around the Hash Table.

- Hash Table Guests:

- Tom Quinn: CISO - T. Rowe Price

- Rick Doten: CISO - Carolina Complete Health

- Link: Podcast

- Link: Transcript

- No Essay

16 MAY 2021

CWX: Zeroing in on zero trust.

- Guests:

- John Kindervag, Cybersecurity Strategy Group Fellow at ON2IT

- Tom Clavel, Global marketing director at ExtraHop (sponsor)

- Link: Podcast

- Link: Transcript

- No Essay

17 MAY 2021

CSOP S5E5: New CISO Responsibilities: Identity

- Hash Table Guests:

- Jerry Archer, Sallie Mae's CSO

- Greg Notch, the National Hockey League's CISO

- Link: Podcast

- Link: Transcript

- Essay: None

30 AUG 2021

CSOP S6E7: Pt 1 - Cybersecurity first principles - adversary playbooks.

13 SEP 2021

CSOP S2E8: Pt 2 - Cybersecurity first principles - adversary playbooks.

- Hash Table Guests: None

- Ryan Olson, the Palo Alto Networks (Unit 42) Threat Intelligence VP

- Link: Podcast

- Link: Transcript

- No Essay

References.

"2016 Presidential Campaign Hacking Fast Facts,” by CNN Library, 31 October 2019, Last Visited 5 January 2020

“About the Democratic Party - Democrats.” 2021. Democrats. September 21, 2021.

“All Signs Point to Russia Being behind the DNC Hack.” 2016. Vice.com. 2016.

"Assessing Russian Activities and Intentions in Recent Elections: Statement for the Record,” by Bill Priestap, Assistant Director, Counterintelligence Division, Federal Bureau of Investigation, Statement Before the Senate Select Committee on Intelligence, Washington, D.C., 21 June 2017.

"Bears in the Midst: Intrusion into the Democratic National Committee,” by Dmitri Alperovitch, Crowdstrike Blog, 15 June 2016.

"CrowdStrike, Ukraine, and the DNC server: Timeline and facts,” By Cynthia Brumfield, CSO, 3 DECEMBER 2019.

"Demystifying CrowdStrike Conspiracy Theories—Cyber Saturday,” By Robert Hackett, Fortune, 28 September 2019.

“DNC Hires First Ever CSO ahead of 2018 Midterms.” Bing, Chris. 2018, CyberScoop. January 25, 2018.

“Fact Check: Meme Makes False Claims about Media’s 2016 and 2020 Election Coverage.” Link, Devon, USA TODAY. November 25, 2020.

"For Mueller, pushing to finish parts of Russia probe, question of American involvement remains,” by Devlin Barrett, Matt Zapotosky, Carol D. Leonnig and Shane Harris, Washington Post, 14 July 2018.

“GRIZZLY STEPPE – Russian Malicious Cyber Activity,” by NCCIC / FBI, Reference Number: JAR-16-20296, December 29, 2016.

“Hacks : the inside story of the break-ins and breakdowns that put Donald Trump in the White House.” Donna Brazile, Published by Hachette Book, November 7th 2017.

“History :: Joint Readiness Training Center and Fort Polk.” 2021. Army.mil. 2021.

“History of Military Gaming.” 2021. Www.army.mil. 2021.

“How to Be Safe from Phishing Sites | They Can Steal Your Data and Info.” 2021. The Ultimate Mobile Spying App. May 3, 2021.

"Indicting 12 Russian Hackers Could Be Mueller's Biggest Move Yet,” by Garrett M. Graff, Wired, 13 July 2018.

"Indictment,” Robert Mueller, Special Counsel, U.S. Department of Justice, 13 July 2018.

"Kill Chain Analysis of the DNC Hacks,” by Rick Howard, Linked-In, 6 January 2020.

“Sandworm: A New Era of Cyberwar and the Hunt for the Kremlin's Most Dangerous Hackers,” by Andy Greenberg, 2019.

“National Democratic Fundraising Committees Catch up with GOP, Reversing Recent History - OpenSecrets News.” Holzberg, Melissa. OpenSecrets News. July 27, 2021.

“Our Work with the DNC: Setting the Record Straight.” Editorial Team. Crowdstrike.com. June 5, 2020.

"State officials say Russian hackers stole 76K Illinois voters' info in 2016, not 500K,” By RICK PEARSON, CHICAGO TRIBUNE, 8 August 2018.

“The perfect weapon : war, sabotage, and fear in the cyber age.” David E Sanger, Published by Crown, October 19, 2021.

“The Sandbox: An Intellectual History.” Lange, Alexandra, Slate Magazine, June 15, 2018.

“Timeline: How Russian Agents Allegedly Hacked the DNC and Clinton’s Campaign.” Bump, Philip. The Washington Post. July 13, 2018.

“Top 16 Most Famous Battles in History - Feri.org.” Kan Dail. 2020. Feri.org. September 22, 2020.

"Why President Trump asked Ukraine to look into a DNC "server" and CrowdStrike,” by Scott Pelley, 60 Minutes, 16 February, 2020.